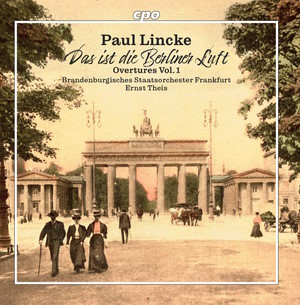

Paul Lincke (1866-1946)

Overtures Volume 1

Berliner Luft (1904)

Lysistrata (1902)

Casanova (1913)

Venus auf Erden (1897)

Grigri (1911)

Verschmähte Liebe (Walzer) (1898)

Siamesische Wachtparade (1902)

Ouvertüre zu einer Operette (1926)

Ouvertüre zu einem Ballett (1919)

Brandenburgisches Staatsorchester Frankfurt/Ernst Theis

rec. 2020; Messehalle 1, Frankfurt Oder, Germany

cpo 555428-2 [65]

I just knew that I had come across the name Paul Lincke before but it took me quite some time to remember where. It turned out to be half way through the second disc of a Decca Eloquence twofer – Homage to Pavlova (Decca 480 4877), in which Richard Bonynge conducts the London Symphony Orchestra in dance pieces specifically associated with Anna Pavlova, probably the world’s most famous ballerina before her death in 1931. One of the tracks on that CD was The glow-worm idyll from Lincke’s 1902 operetta Lysistrata, musicthat, after being picked up as a potential stand-alone pas de deux by the dancer, became more widely known as the Gavotte Pavlova. It was, in its day, a well-regarded showpiece, with one contemporary commentator, quoted in the Bonynge disc’s booklet, suggesting that “the nobility and distinction of this dance, the clearness of its composition, and the charm of style are carried to the highest degree of perfection”. Although the tune, a favourite with Palm Court orchestras, remains familiar to this day, I can’t say that it had ever been enough on its own to inspire me to investigate its composer any further.

The fact that CPO are billing this release as Overtures vol. 1 suggests, however, that they at least are putting quite a bit of faith in the selling power of a composer who isn’t exactly a household name – except, perhaps, in Berlin, for it turns out that Paul Lincke is remembered primarily these days as the composer of Berliner Luft. That particular march is often regarded as the German capital’s unofficial anthem and is trotted out for celebratory civic occasions or as an encore by the city’s orchestras. Various YouTube videos show it conducted by the likes of Mariss Jansons, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Placido Domingo and Daniel Barenboim (who brusquely shushes over-enthusiastic singers while couples quite literally dance in the aisles). You’ll also find both Gustavo Dudamel and Simon Rattle letting their hair down by temporarily relinquishing their conducting duties – the former to take up a violin and the latter clearly having a whale of a time on the bass drum. As far as I can discover, the somewhat more patrician Herbert von Karajan doesn’t seem to have been quite so fond of Berliner Luft – but then, as is well known, his own preference was for somewhat more culturally toxic Prussian military marches.

What, then, is Berliner Luft’s appeal? No attempt at special pleading will convince me that its enduring – if somewhat localised – popularity derives from the lyrics penned by Lincke’s regular collaborator Heinrich Bolten-Baecker, for even their English translator’s best efforts cannot redeem them: That’s the famous Berlin atmosphere / Sweet with aromatic joy and cheer / Seldom do things turn out sad or drear / In the joy and cheer / Of this atmosphere. We can only conclude that the march’s dogged longevity must be due to Lincke’s catchy earworm of a tune.

The booklet notes of several previous CPO releases have featured some well-nigh incomprehensible philosophical essays that have often left me more puzzled than better informed. On this occasion, however, I’m pleased to report that Stefan Frey’s notes are a model of clarity and provide a welcome introductory guide to their subject. For the benefit of MusicWeb readers as unfamiliar with Paul Lincke and his music as I was before encountering this disc, a brief outline, based with grateful acknowledgment on Mr Frey’s enlightening essay, may prove useful.

Lincke’s career as a composer progressed through a number of distinct stages. Having begun in 1884 as a bassoonist and occasional conductor for a beer garden orchestra, he then moved into small theatres that specialised in light music in a variety of forms. He achieved greater prominence from 1893 onwards as conductor of Berlin’s most popular music hall, the Apollo Theatre. There he provided the music for mixed – and apparently somewhat racy – entertainment programmes that might typically include “dance-tableaux”, projections of early silent films, acrobatic feats performed by the Schenk brothers or songs from the popular warbler Mizi Gizi. The Apollo also gave Lincke the opportunity and the means to showcase his own compositions. Initially those were single-Act and commercially very successful Singspiele, but they gradually evolved into a local “Berlin” form of operetta that derived from – or sometimes blatantly copied – Parisian models but possessed its own unique characteristics.

Lincke’s growing reputation meant that in 1897 he was offered and accepted a conducting post at the Folies Bergère in Paris, where, as a fashionable, dashing man about town, it seems that he soon became as famous for his many love affairs as for his well-received conducting. Frey repeats an anecdote that, hearing tales of her husband’s infidelity, Frau Lincke travelled all the way from Berlin to Paris, strode into the theatre mid-performance and slapped her husband’s face as he was conducting. The audience, it is said, burst into spontaneous and enthusiastic applause. Whether or not at his wife’s insistence, by 1899 Lincke was back in the German capital and launched upon a series of fully-fledged operettas that included Frau Luna (1899) in which a party of Berliners are whisked off to explore the moon, Nakiris Hochzeit (1902) which sees German travellers experiencing the delights of Thailand and Lysistrata (1902), a vaguely satirical adaptation of Aristophanes’s comedy that was somewhat curiously billed as a “fantastical operetta-burlesque”.

Thereafter, however, as musical fashions changed and new operetta composers including Franz Lehar, Leo Fall and Oscar Strauss rose to prominence, Lincke’s musical style began to be regarded as somewhat passé. Gri-Gri (1911), his first full-length three-Acter, was a failure in Berlin, as was the equally ambitious Casanova (1913). Retiring from composing for the stage, he thereupon refocused his energies largely on music publishing, although he enjoyed a brief reputational Indian summer following his 70th birthday celebrations in 1936.

So much for the man – but what of the music? The overtures heard on this disc are essentially potpourris of operetta melodies. Sometimes quite lightly orchestrated, presumably because of the smaller theatre bands for which Lincke was writing, they are all quite enjoyable in a swaying-in-the-aisles or foot-tapping way but, to be honest, some of them aren’t terribly memorable. Even the Berliner Luft overture would be little more than a mere divertissement and surely long forgotten had it not been for its rousing singalong finale (all I can assume is that the words must sound better in German). Of the rest, I was most taken by Lincke’s later, more ambitious compositions. Grigri sees his music elevated to a new level of sophistication, making one wonder whether he felt he had to raise his game to meet the challenge posed by Lehar and the others. Meanwhile, Casanova’s overture – including an attractive pastiche of a Mediterranean serenade (05:38-07:02) – is perhaps the most immediately appealing music to be heard on the disc. The early Venus auf Erden overture also deserves an individual mention. Energetic and driven, it goes with an attractive, crowd-pleasing swing and impresses as more of a unified concept than some of Lincke’s other early and somewhat more piecemeal works. The waltz sequence Verschmähte Liebe – a surprisingly upbeat composition given that its title translates as Unrequited love – is quite delightful and an undoubted success, while the late stand-alone pieces Ouvertüre zu einem Ballett and Ouvertüre zu einer Operette demonstrate the composer’s undoubted and undiminished skill, even if their precise characterisation is sufficiently sketchy as to make the titles entirely interchangeable.

CPO’s engineers have made a splendid job of recording these pieces and the skilfully delivered performances by the Brandenburgisches Staatsorchester Frankfurt are thereby heard to best advantage. Conductor Ernst Theis, though not a native Berliner, is clearly a master of Lincke’s idiom and delivers the scores affectionately, expertly deploying vigour or sentimentality as required.

Mentioning the conductor, it is worth noting that in some “personal notes” included in the CD booklet Mr Theis, makes some bold – if, as he concedes, entirely subjective – claims for Lincke’s music. Because they are so strongly and strikingly expressed, I will quote them here in full. “Lincke’s art for me”, writes Mr Theis, “is that he can achieve expression in simplicity and also in complexity of his musical ideas, that his overflowing wealth of musical invention never becomes trivial or ingratiating, that his music does not necessarily need a libretto, but that the stories of his libretti always resonate, that his music can create literally imaginary spaces in which emotions bubble up, touching people dramatically in the sense of releasing exciting tension, whether it is funny, charming, serious, saucy, transparent, superficial or hidden, accompanying or obtrusive… that the dramaturgy of his works develops musical form that wants to reach people directly, [and] that his musical invention always strives for artistic richness and not first of all for economic success with the cheapest possible means…”

Those are certainly ambitious claims and, while they may, for all I know, be entirely justified if applied to the composer’s oeuvre as a whole, on the basis of the single volume of overtures with which we’ve so far been presented I’m not fully convinced. The furthest that I’d be prepared to go at this stage is to observe that Lincke undoubtedly knew how to craft pieces that would, for most of his career, appeal successfully to the audiences for which he was writing. He was a jobbing composer and nothing that I have heard so far on this disc suggests he was aiming to compose music that would challenge his listeners too much. There is, of course, nothing wrong with that. There was plenty of space in the early 20th century European music scene for composers who aimed for the popular market and never aspired to emulate the likes of Mahler, Zemlinsky or Schoenberg – and Paul Lincke was one of those who happily filled it.

On the evidence of this first disc in its series, I would, however, say that there is already something of a caveat to be registered. While it is clear that Lincke was able to produce crowd-pleasing material, some of his individual pieces are lacking in individuality. Their musical styles frequently appear only marginally – if at all – related to their supposed settings. One might surmise that, knowing what his audience liked hearing and hitting on a winning formula in producing it, for much of his career Lincke chose not – or perhaps wasn’t able – to vary his style appropriately so as to suit differing musical/dramatic scenarios. It will suffice to mention just a couple of examples. The Lysistrata overture opens with fanfares that might, at a pinch and if you were so inclined, bring Ancient Greece to mind, but they are immediately followed (00:50-01:36) by a tune that’s more evocative of a fashionable turn-of-the-century boulevardier strolling languidly along Unter den Linden. Similarly, the Siamesische Wachtparade from Nakiris Hochzeit features a company of elite Thai soldiers coming onto the stage to music that suggests that they’ve arrived from Charlottenburg rather than Chiang Mai.

I could, of course, be wrong. Perhaps, with further volumes in this series still to come, we will find that Lincke is a composer with rather more strings to his bow than we have, so far, been led to suspect. It will certainly be interesting to see whether or not that will prove to be the case.

Rob Maynard

Help us financially by purchasing from