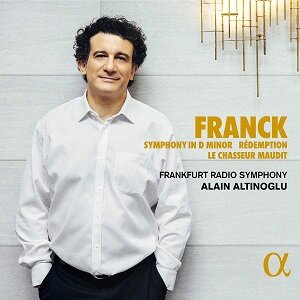

César Franck (1822-1890)

Symphony in D minor (1888)

Symphonie de ‘Rédemption’ (1ère version de 1872) dit “Ancien morceau symphonique”

Le chasseur maudit

Frankfurt Radio Symphony/Alain Altinoglu

rec. 2022, HR-Sendesaal, Hessischer Rundfunk, Frankfurt

Alpha Classics 898 [61]

How musical fashions change! Few LP collectors in the 1950s would, I’ll venture, have anticipated the huge explosion that was about to occur in recordings of Bruckner’s and Mahler’s symphonies. Equally, they’d no doubt have been astonished to see the steady decline in the number of recordings of many of the so-called warhorses that were, back then, staples of the catalogue. Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade and Franck’s D minor symphony, to take just a couple of examples, share not only their composition date – August 1888, since you ask – but the fact that each is nowadays a comparative rarity in lists of new releases.

We are, nevertheless, spoiled for choice when it comes to admired recordings of the symphony in D minor. For many, Pierre Monteux’s 1961 account with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (RCA Living Stereo 09026 63303 2) remains nonpareil. Sir Thomas Beecham’s recording with the French National Radio Orchestra, made in 1959, is also still much admired (EMI Classics 9099322) and, in the same way that I am drawn to Willem Van Otterloo’s 1964 Concertgebouw performance (Challenge Classics CC72383), others will have their own particular wild-card favourites. Incidentally, you won’t need to be Sherlock Holmes to have noticed that those three examples all date from the 1950s or 1960s, for those two decades witnessed a remarkably large number of recordings of the Franck symphony. Indeed, I could very easily have extended my list by including performances from the likes of Charles Munch, Antal Doráti and Paul Paray.

All those accounts are, though, more than 50 years old and some collectors may insist on sound that at least approaches the standards that we have come to expect as the norm in the 21st century. There’s a very good recording that I reviewed last year from Christian Arming and Franck’s home-town orchestra, the Orchestre Philharmonique Royal de Liège, but it is only available as part of a four-disc set of Franck’s orchestra output (Fuga Libera FUG791) and that may prove an unnecessary expense for some. Perhaps, then, this Alpha Classics release may be what’s wanted.

Conductor Alain Altinoglu’s credentials in performing this music certainly appear impressive. Born in Paris, he was educated at the city’s conservatoire and went on, like Franck himself, to become a teacher of conducting there. After leaving that position in 2014 and subsequently taking up the post of music director of the La Monnaie opera house in Brussels, he naturally became a frequent visitor to Belgium, the country in which the composer had been brought up before moving to study in France. Meanwhile, he also took up the position of chief conductor of the Frankfurt Radio Symphony, an orchestra that, under the 12-years direction (2006-2014) of Paavo Järvi, had developed a notably keen affinity – not least on disc – with the Late Romantic repertoire. Although this is the first Frankfurt Radio Symphony/Altinoglu disc to have been released, the conductor is certainly no newcomer to the recording studio and several of his previous recordings have been favourably reviewed on this website.

Mr Altinoglu’s approach to the Franck symphony is a relatively direct one. If you click on the link to the Doráti recording given above, you will find a table in which I listed the three movements’ timings in 13 different recordings. Of course, timings in themselves aren’t the be all and end all, for we all know that a skilful conductor can make music sound fleet of foot – or as if it’s being held back – even when the stopwatch indicates that it really isn’t. Nevertheless, the ticking clock does have something to tell us in the broadest terms and, in this case, it fully confirms the ear’s impression that Altinoglu takes a notably driven approach in both the first and second movements. With a timing for the former of 16:20, Altinoglu proves more propulsive than Mengelberg, Toscanini, Rodzinsky, Beecham, Monteux, Maazel, Barbirolli, Van Otterloo, Stokowski, Doráti, Bernstein and Svetlanov – only Paray delivers the music at a swifter overall pace. Much the same is true of the second movement, where only Paray and Mengelberg beat Altinoglu (9:10) to the finishing post and the other 11 conductors all lag behind to greater or lesser degrees. In the symphony’s finale, Altinoglu is again one of the speedier accounts.

Notwithstanding those timings, this is a performance that does not sound over-hurried as such. Rather, it is generally brisk, tightly constructed and consistently focused. Entirely eschewing self-indulgence, the opening movement, after a rather beautifully sculpted introduction, knows exactly where it’s going and is determined not to dawdle along the way. The lithe, supple playing of the Frankfurt orchestra is, in this movement as elsewhere, a sheer delight. The same sense of unerring direction characterises the allegretto second movement which, in other accounts, can sometimes give the impression of amounting to little more than a lightweight intermezzo that meanders along in a somewhat self-absorbed fashion. Altinoglu pushes the music along here with pointedly characterised rhythmic propulsion (3:48-4:34) that cuts down on dreaminess, it’s true, but integrates it more effectively with movements I and III. While the finale begins at a fair lick, this time the pace isn’t maintained as relentlessly and the conductor shows more willingness to slow down and take stock, as it were, from time to time (at, for instance, 1:46-2:28), thereby introducing an element of contrast that hadn’t been as apparent in the previous two movements. Meanwhile, his keen ear for orchestral balance shines a piercing light through Franck’s sometimes dense orchestration, producing a degree of transparency that reveals plenty of felicitous inner detail. The finale’s climax (7:38 onwards) is beautifully achieved, with the harp passages well integrated into the orchestral mix and bubbling away atmospherically as they lead in to the symphony’s triumphant peroration.

Given that the symphony is well under 40 minutes in length, the new disc has been augmented, as you would rightly expect, with other material. The tone poem Le chasseur maudit, Franck’s musical depiction of a Sabbath-breaking horseman cursed to be chased forever by demonic forces, is a fairly safe and predictable choice. Rather rarer – if only because it was, for many years, a lost score – is the original 1872 version of the Rédemption morceau symphonique, music so disliked by contemporary audiences that the composer replaced it with the revised version that’s more familiar today.

The performances of those two works are just as well thought-out as that of the symphony and just as impressive in their delivery. Given an accomplished performance such as we are offered here, it is difficult to understand why audiences didn’t particularly take to the 1872 version of Rédemption; anyone wishing to investigate further will find both it and its later replacement in the Fuga Libera box set to which I made earlier reference. Mr Altinoglu’s commitment to Le chasseur maudit, meanwhile, cannot be questioned. He and his players deliver an involving and exciting performance, characterised by splendidly in-your-face percussion that makes a dramatic impression at the work’s climax. This is at least the equal of any other recording. First-class sound quality only enhances the disc’s appeal, as does a brief but usefully informative booklet essay by Adam Gellen.

Mention of the booklet reminds me, however, to point out a potentially confusing typo in the disc’s packaging, for while the disc’s catalogue number appears as 898 in the booklet and on its spine, it is given as 896 on its rear cover. Reference to the Alpha Classics website confirms that the correct number is 898.

After this auspicious debut release, I will certainly look forward to hearing more from Mr Altinoglu and his Frankfurt orchestra – even if the latter has regrettably chosen to follow the fashionable trend of rebranding itself in such a way as to deny that it actually is one.

Rob Maynard

Help us financially by purchasing from