Déjà Review: this review was first published in June 2011 and the recording is still available.

Max Bruch (1838-1920)

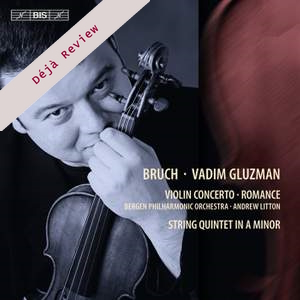

Violin Concerto No 1 in G minor, Op 26 (1864-68) [24.17]

Romance in F, Op 85 (1911) [8.30]

String Quintet in A minor, Op. posth. (1918) [24.05]

Vadim Gluzman (violin)

Sandis Šteinbergs (violin); Maxim Rysanov (viola); Ilze Klava (viola); Reinis Birznieks (cello)

Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra/Andrew Litton

rec. 2009, Schloss Nordkirchen, Orangerie, Westphalia, Germany; Grieg Hall, Bergen, Norway

BIS BIS-SACD-1852 [58]

An understandable reaction to yet another performance of Bruch’s first violin concerto would surely have elicited much eye-rolling and a lot of invective from the composer, who always exhorted violinists to play one of the other eight concerted works for the instrument. As his biographer I can guarantee that. Yet I would be surprised if he did not like what he hears here. Vadim Gluzman, with a finely attentive accompanist in Andrew Litton and his responsive Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, plays it superbly – it’s quite the finest performance I have ever heard, including Kreisler’s famous 1925 recording. While transitions to tempo changes may strike one as over-stated, there is immense detail, subtle, sometimes rightly unsubtle, nuance and robust energy in the playing, as well as lingering lyricism. Clean cut double-stopping in a Hungarian goulash of a finale peppered with spice and rushing to a headlong conclusion will leave the listener breathless. The central Adagio avoids sentimentality while giving full rein to its Romanticism in long-arched phrasing and sweet tone, this after a ruggedly presented Prelude (itself starting with an almost too inaudible pp timpani roll). This account reminds us of the timely arrival of this work in 1868 between Mendelssohn’s and Brahms’ contributions to the genre, but more significantly it shows us how much Bruch was influenced by the former and in turn influenced the latter.

If nothing else, it made financial sense for Bruch to make versions of his music for other instruments to play and while he did not (to my knowledge) envisage his viola Romance being accompanied by an orchestra, he certainly did offer a version with piano accompaniment. Pragmatism dictated the sense of doing so for after all there were and still are more solo violinists about than solo violists. It is a beautiful work, hard to programme because of its awkwardly short length but ideally suited for inclusion on a recording. One misses the viola’s lowest fifth from G to C which Bruch always loved in much-favoured alto register instruments (clarinet, cello and French horn were often prominent in his orchestration), but Gluzman’s fine playing is fair exchange in this very interesting and rewarding exercise – and there is always Gérard Caussé’s fine account on Erato of the original version for the viola.

At the end of his life Bruch – like so many other composers – returned to chamber music. At the start of his career in the early 1860s he produced a piano trio and two string quartets, but apart from a mid-life piano quintet in 1886, he wrote nothing else until two quintets and an octet all for strings in 1918/1919. They in no way sound as if the Rite of Spring was five years old, nor that Bartók and Schoenberg were well on their way to establishing themselves on the music scene. Instead they remain rooted in the 1860s when Bruch was writing his best music. Ferdinand David, Joachim and Sarasate were consulted when writing all his earlier works for violin, but they were all dead by 1918 so it was now the turn of Willy Hess to take on that advisory role. The result is that the first violin is the virtuoso while its four colleagues (including a second viola) take on a comparatively subsidiary role (also true of the other quintet and the octet). Needless to say Gluzman rises to the occasion if not beyond. His masterly technique is admirable and recalls Ulf Hoelscher’s disc for CPO. If, as one would assume from a lack of a name for this ensemble, this is a put-together group who have met for the recording, one can only praise their blend and balance as well as unity of phrasing and control of passage-work.

This is an enterprising combination of works by Max Bruch, given superb performances by everyone involved, not forgetting the sound engineers and post-production editors Fabian Frank, Martin Nagorni, Hans Kipfer and Michaela Wiesbeck, who too often go unappreciated in our perception of the recording industry.

Christopher Fifield

Help us financially by purchasing from