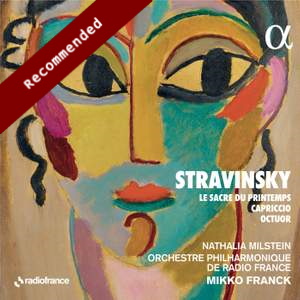

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)

Capriccio (1929)

Octuor (1923)

Le Sacre du Printemps (1913)

Nathalia Milstein (piano)

Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France/Mikko Franck

rec. 2020/21, Auditorium, Radio France, Paris

ALPHA CLASSICS 894 [68]

The circumstances surrounding the first performance of Le Sacre du Printemps in 1913 are well known. One account has it that the cat-calling and mocking laughter started pretty much immediately, a response to the opening notes from the first bassoon. Other accounts, perhaps more sober, suggest that it was Nijinsky’s choreography as much as the music itself that displeased the Parisian public. Either way, I recently attended a concert at the Théatre des Champs-Elysées for the first time and found myself pondering on how, in those days, a new work of classical music might provoke such a violent reaction. One can think of certain works in recent years that have been subjected to seriously negative criticism, but the idea that audiences care passionately enough to create a scandal seems to be a thing of the past.

Pierre Monteux conducted that first performance, and one wonders just what it sounded like. Instrumental technique has advanced so far since then that today’s orchestras – youth orchestras included – take the Rite in their stride. Indeed, watching a video recently of Simon Rattle conducting the work I was persuaded that for all his virtuoso time-beating in the final Sacrificial Dance, where the time signature changes almost bar by bar, the orchestra could have played it without him. In spite of all this, one remains in awe of the capacity of a huge orchestra to achieve unanimity in such a complex score. One is certainly in awe of the Orchestre National de Radio-France in this performance. They play with stunning virtuosity.

From the pensively played opening notes – that bassoon solo! – one is struck in this performance by the clarity of texture. On hears pretty much each individual instrumental strand: accuracy, tuning, balance and dynamics are all totally under control, and the work of the production team surely plays a part too. When the pizzicato strings announce the Dances of the Young Girls we know that it will be fleet-footed as regards tempo, and the notorious, hammered, irregularly accented dissonant chords that follow are certainly not so aggressive as can be heard in other performances, reminding this listener that only a couple of years separate this work from Petrushka. Now I had already read a review of this disc before listening – never a good idea! – and was prepared for this, but luckily it did not colour my reactions to the rest of the performance. That reviewer found wanting the crashes of the gong in the Spring Rounds, yet the score shows that those notes are not even marked forte, but simply ‘Heavily but not too much’. The remorseless tread of that passage leads to a Procession of the Sage and Dance of the Earth that are as thrilling as I have ever heard them.

Among other points that particularly pleased me – and there are too many to mention them all – would be the timbre of the four solo violas in the Spring Rounds, the sheer brilliance of the playing in the very rapid Glorification of the Chosen One, and the jazzy feel to the syncopated chords that make up the Evocation of the Ancestors.

To sum up, though the Rite came as a profound shock to the Paris audience in 1913 we no longer find it shocking today. Or do we? This performance, as we have come to expect, is technically impeccable. The apparent ease of execution takes away most of the work’s capacity to shock. The music itself has not changed, however, and I think a young listener, starting out on a whole life’s musical journey, will indeed be shocked by the Rite, just as I was when I first heard it. This magnificent performance, from the city where the work was first propelled into the world, will do the job just as well as any other, and better than most.

The Rite is preceded by two works from the composer’s so-called neo-classical period. The Capriccio was completed in 1929, which makes it almost contemporary to the Symphony of Psalms. Stravinsky himself played the solo part in the first performance, under the direction of Ernest Ansermet. The work is spiky, highly rhythmic, with an irresistible moto perpetuo finale. The orchestral strings are divided into concertino and ripieno sections as if it were a Brandenburg Concerto, but it is the wind sonority that dominates. The soloist is kept busy throughout, though there is not much in the way of lyrical or melodic writing. It is played by the young French pianist Nathalia Milstein. She is absolutely superb, and it is shameful that there is not one word about her in the booklet.

Stravinsky’s quirky Octet – quirky, also, in the forces required: flute, clarinet and two each of bassoons, trumpets and trombones – completes the programme. This beautiful performance confirms, if confirmation were needed, that the wind sections of the Radio France orchestra are made up of world-class players. Their superbly refined playing – they are named in the otherwise rather skimpy booklet – brings out all the nuances of this deceptively sophisticated work and reminds us that Stravinsky was a composer of ballets. The crescendo that leads into the delicious coda, unsanctioned by the score, is so effective that it justifies itself. And that coda, a kind of gently jazzy choral, is played with the kind of relaxed cool that defies criticism.

William Hedley

Help us financially by purchasing from