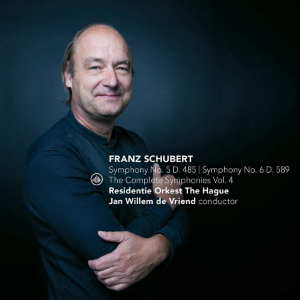

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Symphony No. 5 in B flat, D485 (1816)

Symphony No. 6 in C, D589 (1817-18)

Residentie Orkest The Hague/Jan Willem de Vriend

rec. 2022, Concertzaal Amare, The Hague, The Netherlands

The Complete Symphonies, Vol. 4

CHALLENGE CLASSICS CC72803 SACD [61]

This fourth volume completes Jan Willem de Vriend’s Schubert Symphonies’ cycle with the Residentie Orkest, The Hague. In Symphony 5, Schubert’s Pastoral Symphony, de Vriend secures a bright sound, clear accents and lightly sprung athleticism to the first theme but still bite to the first tutti (tr. 1, 0:45) with its more forceful variant of the opening theme. The second theme (1:10) is calmer but for me a little too articulated, blunting the relaxation. In the soft opening of the development (4:10) I feel the first violins’ descents, the first motif heard at the symphony’s start, are thrown off too timorously in relation to the second motif, the opening of the symphony’s first theme, now shared by flute and first oboe. In the transition to the recapitulation the soft conversation (from 4:40) between flute, first oboe and violins and retorts from second oboe, bassoons and violins could benefit from a little more sense of reflection. However, de Vriend’s recap itself has a lovely soft sheen.

I compare this with the 2018 SACD recording by the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra/Edward Gardner (review). This has equal impetus and bite but gains from a more relaxed, sweet and charming treatment of the second theme, clearer staccato first violins’ descents in the development and more reflection in the conversation approaching the recap.

The Andante con moto slow movement is from de Vriend mild and graceful. His first theme’s second strain opens out with flickers of anxiety, aided by his fair observation of the con moto which equally assists a swift coaxing back into equilibrium where the flute and later oboe soften the mood. The second theme (tr. 2, 2:38) is more wary in its exploration, first violins accompanied by or alternating with oboes and bassoon and then flute, the latter again brightening the texture. Now tutti sforzandos send shudders through it, but of a paper tiger, soft pointing and resolution being more pervasive. The coda (7:54) is untroubled, serenely nostalgic in the closing chromaticism of the second violins and violas (9:08), capped by the soothing E flat arpeggiando on the horns.

Gardner, timing at 8:09 to de Vriend’s 9:27, makes more of the con moto but not, for me, to advantage. The dense texture seems congested and the ornamentation fussy. This is more summer-filled than de Vriend, yet the return of the second theme is pleasingly delicate. I appreciate more de Vriend’s greater simplicity and clarity, illuminating how the orchestration meshes, its patient working through the development and clear direction.

As in Mozart’s Symphony 40 Schubert has a Minuet in G minor and Trio in G major. Schubert, however, dispels the gloom more quickly, brushing aside the initial grimness by the second half of the opening strain. A more poetic unease graces the second strain, lingering through more sustained melody and eloquent sighs from the first oboe, but brushed aside the same way. De Vriend does this all effectively. The Trio (tr. 3, 2:18) has the lovelier, benign melody with a warm first bassoon solo doubled by first violins, while in its second strain these forces are liltingly echoed by flute and first oboe. De Vriend takes the Trio a little more spaciously, suiting the change of sentiment.

Gardner times at 4:38 against de Vriend’s 4:56, but I feel de Vriend obtains more emotional contrast. Gardner’s more business-like Minuet lacks de Vriend’s grimness. Yet in this context Gardner’s slower Trio seems more so and creamier.

The finale, despite his tidy, unobtrusive opening, is well pointed by de Vriend so its Allegro vivacehas a rhythmic edge leading to burgeoning enthusiasm in the second strain with tremolando violins’ climax and a second part (tr. 4, 1:02), ff, with sforzandos and rising scales in violins and string bass. All this is dissipated by the unconcerned charm of de Vriend’s second theme (1:31). The development (5:06) modifies the opening theme into a terser, more thrusting force, but for me de Vriend should be still more thrusting so the repeated rising opening phrase has more impact before with more contrast being more softly considered (5:33) transitioning to the recap.

Gardner times the finale at 6:48 against de Vriend’s 8:37, stressing the latter element of Allegro vivace to merrier effect, alongside which de Vriend seems painstaking but rather deliberate. Gardner’s opening is soft, but more eager and friskier than de Vriend’s. Gardner’s second theme as well as charm has more sweetness. His development is more urgent and makes more impact before its more marked soft contrast.

Symphony 6 is Schubert’s entertainment symphony. But not its Adagio introduction, scrupulously played by de Vriend which seems a blustering man’s show of ffz force against a lady pointing out the soft, intricate embellishments of life, from her demisemiquaver rises responding to the ffz chords to the indulgent dalliance of the expansive solos of clarinet and later flute. These latter I feel de Vriend over considers, blunting their provocative ease. In the Allegro (tr. 5, 1:50), by having the opening theme, soft but rollicking in the flutes, repeated with a mix of loudness then softness by the violins and then the flutes’ soft echoes of the tutti, the tensions of the introduction are resolved with a coming together of the two parties while the second theme from flute and clarinet (2:33), like the first of gay abandon, showcases syncopation instead of the first’s appoggiaturas. Its second phrase eventually spawns a third theme on clarinet and bassoon followed by flute and oboe (3:02), the first melody which rises at the end, but it’s just a foil for a modified recollection of the second theme’s descent exchanged luxuriously by all the woodwind and first violins. The development (5:35) tries for a braggadocio version of this in unison strings, but the woodwind and first violins soon reinstate their milder version in a transition (5:45) incorporating a gentle recapitulation of the first theme, de Vriend at his most fluently, musingly poetic before the earlier high-jinks return, enhanced by the faster coda (8:26).

The Andante slow movement begins Haydnesque with delightful, static simplicity, luminously orchestrated, which de Vriend does well. Schubert gives the flute such an airy, buoyant appeal. Then there’s plenty of contrasting verve in the central section (tr. 6, 2:11), but late in its soft second strain (2:56) two flutes spotlight an accompanying ornamentation that recalls and emphasises what has earlier been a general woodwind specialty and continues even more suited to the freer return of the opening section (3:44) with the melody having gained clusters of semiquavers. It can then soon dismiss the return of the central section (4:34) when the flute and clarinet happily grace the first violins’ dancing (4:49) and a coda (5:16) of blithe eloquence.

In the Presto Scherzo you think of Beethoven, but Schubert is friendlier. In the second section (tr. 7, 0:48) for me de Vriend’s quieter passages, especially the flutes and clarinets, sound too serious. Gardner and the CBSO in his 2019 recording (review) make them skip more. The più lento Trio (2:49) brings a clash of sustained chords, especially in horns and trumpets, with the melody shared by upper woodwind and strings. I think of the Trio of Beethoven’s Symphony 7 (1813), but its purpose is dominating power where Schubert’s flutes and clarinets’ melody and, in the third strain (3:33), the violins’ accompanying quavers, are playful, which suggests the fps should be more nudges than stabs, which is how Gardner plays them, timing the movement at 5:31 against de Vriend’s 6:10. This suggests a lighter touch by de Vriend would be appropriate to the overall scoring and I’d suggest more generally.

The Allegro moderato finale, altogether Schubertian and in comic vein, is unproblematic. The strings introduce a light opening theme with quipping extracts shared between them and the flutes and oboes even towards the end of the first strain. The tuttis inevitably come in the third strain (tr. 8, 1:31) but are good-hearted banter rather than a show of force and de Vriend does these at first lightly, just serving to introduce a constant accompanying flurry of violins’ semiquavers after which de Vriend’s later tutti interjections get heavier. The second theme (2:13), while quite dance-like, has a more thrustful, heroic manner, yet only mf in flutes and oboes before it comes intentionally to a (mock?) grand cadence, only to be deflated by a fourth strain (2:49), a comic development, with flutes and later clarinets tiptoeing up and down the scale over a dance pulse, the height of trivia, whereupon the tuttis get more bombastic, yet comic too in de Vriend’s abrasive fzs in the string-bass. The coda (8:39) is consistently hearty, Schubert reluctant to conclude it but incorporating splendid fanfares for 2 trumpets (from 9:10). Gardner sends up the movement more, but is more enjoyable for being less serious. He adds tempo fluctuations around the end of strains, especially the first, in wilful individuality. His flutes in the fourth strain are cheekier and he really goes to town in the ffs in the coda and trumpet fanfares.

Michael Greenhalgh

Help us financially by purchasing from