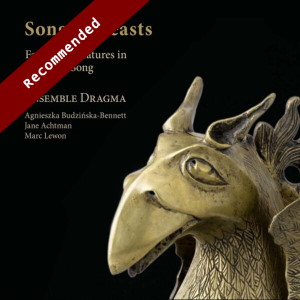

Song of Beasts – Fantastic Creatures in Medieval Song

Ensemble Dragma

rec. 2019, St.-Nikolaus-Kirche, Herznach, Switzerland

Texts and translations included

Reviewed as a stereo 16/44 download with PDF booklet from Outhere

RAMÉE RAM1901 [53]

In the course of history animals have figured prominently in art. In many baroque paintings of family life or social gatherings one can find one or several dogs. Numerous cantatas have been written in which birds, and in pariticular nightingales, appear. Animals were often used as metaphors of situations in human life or to communicate a particular moral message. The present disc brings us to the Middle Ages, when so-called bestiaries were written: illustrated encyclopedias about animals. These were part of the real world of medieval people, but also of a world far away, such as lions and tigers. Also included were mythological creatures. Among the latter are the phoenix and the unicorn.

The programme has been divided into six chapters. In the libretto each is introduced by a writing from the Middle Ages. The first chapter is about exotic animals: the panther and the lion. The first item is one of the most famous pieces from the Italian Trecento: Una panthera by Johannes Ciconia. The virtuosity of the upper part is indicative of the dominant style of the time. Comparable piece are following in the rest of the programme. In this piece we encounter one of the symbolic meanings of animals: they could be used as heraldic symbols. This piece is written in praise of the city of Lucca; the panther or leopard became the symbol of the city during the 14th century.

The second chapter is about hunting, one of the main preoccupations of royalty and aristocracy throughout history. Johannes Ciconia’s I cani sono fuora is a graphic musical depiction of an actual hunting party. However, the hunt was also used metaphorically for the attempts of a man to win over a woman, as is illustrated here in Selvaggia fera by Francesco Landini.

The third chapter includes just one piece: Phiton, Phiton by Magister Franciscus. This refers to the mythological serpent-dragon from a Greek myth, in which Apollo figures. This piece describes the combat between Phoebus (the Latin name for Apollo) and Phyton. For this piece the composer turned to Machaut’s ballade about the same subject, Phyton, le merveilleus serpent.

Chapter IV is entitled “On all Kinds of Birds and their Nature”. It comprises four pieces, three of which are performed instrumentally. The only vocal item is Fenice fu by Jacopo da Bologna, and here we meet again a mythological creature, the phoenix. This piece describes how a woman is transformed from a phoenix to a turtledove. Like other pieces of this kind it is a heraldic piece, probably written for the wedding of Giangaleazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan, to Isabelle de Valois. It is the only piece in the programme performed by two singers, without the participation of instruments. That is compensated, as it were, by the other three pieces. The anonymous Aquila altera is another heraldic piece, again connected to the Visconti family. In this piece the flight of the eagle is depicted, in the also anonymous Or sus vous dormés trop the singing of the lark.

The fifth chapter includes two pieces under the header “Viper, Scorpion and Basilisk”, three venomous creatures. The first piece, by Guillaume de Machaut, is about the viper. As is so often the case, the viper is used metaphorically, as this is about a lady rejecting the efforts of her lover, who complains that “a viper lives in my lady’s bosom”. “[She] is as deaf to his pleas as a viper, her venomous tongue, scorpion-like, rejects him, and her glance, deadly as a basilisk, kills him” (booklet). Interestingly Machaut includes verses from Psalm 58. This piece confirms that in the medieval and renaissance periods (and even after that) there was no watershed between the sacred and the secular. The second piece in this chapter is by Donato da Firenze. In L’aspido sordo four creatures meet: a deaf snake, a mole, a lizard and a basilisk. Agnieszka Budzinska-Bennett, in her liner-notes, states that this piece is enigmatic and is hard to understand for modern interpreters.

The last chapter is called “On Bats and Mice”. These animals seem to have little in common. However, the first piece, En seumeillant by Trebor, is about a bat with mouse ears, a vespertillo. This piece is performed here in a transcription for two plucked instruments. The second piece, the anonymous Deh tristo mi topinello, describes a mouse as a bat without wings. “Sad and hungry, it wants some sausage, fat capons, and tortelli for dinner, although its real menu is very diff erent. Despite its gourmet desires, our mouse is sentenced to eating coarse black bread, radishes and broad beans.” It is a rather simple piece, in contrast to the often highly complicated works that have been performed so far and the least serious of them all.

It brings to an end a fascinating programme, which sheds light on the world of the Middle Ages, its preoccupations and ideas. The music is often technically highly complicated, but musically compelling. I knew Agnieszka Budzinska-Bennett as the director of her ensemble Peregrina, in which she mostly sings together with colleagues. This may well be the first time I have heard her as a soloist, and I am very impressed by the way she deals with this repertoire. This is some of the best singing in music of the 14th century that I have heard in a long time. The effects described in the booklet are perfectly conveyed. Some pieces are performed instrumentally, and as unfortunately their text is omitted in the booklet, the connection between text and music is largely lost. To a certain extent the descriptions of their content in the liner-notes compensate for that, and these are realised very well by Jane Achtman on the vielle, Marc Lewon on the vielle and the lute, as well as Agnieszka Budzinska-Bennett on the harp. Aquila altera is an eloquent example. Lewon is also a fine singer, who is the perfect match of Agnieszka Budzinska-Bennett in Fenice fu.

For lovers of medieval music this is a disc not to be missed. Others should give it a try, and may well start to really like this music and the fascinating world of ideas it represents.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Contents

Help us financially by purchasing from

[Hear me roar]

Johannes CICONIA (c1370-1412)

Una panthera

anon

Ung lion say

[De Arte Venandi – On the Art of Hunting]

PAOLO DA FIRENZE (1355-1436)

Un pellegrin uccel

JACOPO DA BOLOGNA (fl 1340-1360)

Un bel sparver

Francesco LANDINI (c1325-1397)

Selvaggia fera

Johannes CICONIA

I cani sono fuora

[On the serpent Python, born from the excess moisture of the Earth, and how it was slain by Phoebus]

Magister FRANCISCUS (fl 1370-1380)

Phiton, Phiton

[On all Kinds of Birds and their Nature]

anon

Or sus vous dormés trop

Aquila altera

JACOPO DA BOLOGNA

Fenice fu

GIOVANNI DA FIRENZE (fl 1340-1350)

Nel meço a sey paon

[Viper, Scorpion & Basilisk]

Guillaume DE MACHAUT (c1300-1377)

Une vipere

DONATO DA FIRENZE (fl 1350-1370)

L’aspido sordo

[On Bats and Mice]

TREBOR (fl 1380-1400)

En seumeillant

anon

Deh tristo mi topinello