Johannes Brahms (1833-1987)

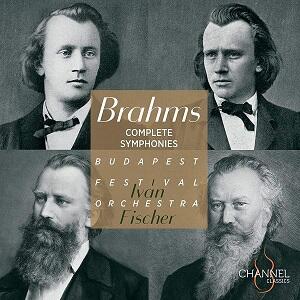

Complete Symphonies

Budapest Festival Orchestra/Iván Fischer

rec. 2009-2020, Palace of Arts, Budapest and Müpa, Budapest

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCSBOX7322 [4 CDs: 255]

There aren’t many Brahms symphony cycles that begin with a Hungarian Dance, especially not one that has been arranged by the conductor. Yet that’s exactly what Iván Fischer’s cycle with the Budapest Festival Orchestra does, now released as a set for the first time.

Is it a statement of intent? A re-envisioning of Brahms from the eastern European perspective? If it is then these musicians are surely the ones to do it. Hungary’s finest orchestra (probably), they tap firmly into the composer’s own interest in the music of the eastern Habsburg empire, and the celebrated “gypsy” components of Brahms’ music probably sound more authentic coming from them than from any other orchestra west of Vienna. Fischer himself describes Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 as the first “German Hungarian Gypsy Swiss Austrian symphony” so you can see that he’s going for the cultural cross-fertilisation.

All very well, but it needs to work on its own musical terms, of course, in order to convince anyone who doesn’t know anything about Fischer’s vision or modus operandi. It also needs to stand up against some pretty ferocious competition, much of it recent. So let’s evaluate it on its own terms, and begin by stating the obvious point that the orchestral playing is terrific throughout. Over his decades in charge Fischer has drilled the Budapest Festival Orchestra into an elite team, and there isn’t a note or phrase in this set that sounds anything less than perfect. You could just as easily say that about orchestras in Vienna, Berlin or London, though, so I suspect that, for most listeners, it’s Fischer’s interpretative vision that will drive their decision. That’s mostly very secure, and often combines the best of the old style of Brahms interpretation with the best of the new. However, that often leaves the music sounding quite middle-of-the-road, and there are interpretative missteps along the way, mostly in terms of pacing.

Things certainly begin well, though. Symphony No. 1 opens at a refreshingly broad tempo, with no Harnoncourt or Ticciati-style rushing (and to my ears it is rushing!), but there’s no titanic thumping of the timps allaFurtwängler or Karajan, either, so everything is integrated and whole rather than dramatically driven. There is silky suppleness throughout the string sound, the same that Fischer finds for the opening Hungarian Dance, and that characterises the main Allegro, too, which is much more exciting than the Sostenuto introduction. Fischer paces it grippingly, swishing through the textures with urgency and forensic insight. There is purposeful forward movement to the Andante, too, though the sheer beauty of the sound is the main quality here, not least the beautifully integrated instrumental solos. Speaking of solos, the “alphorn” in the finale sounds terrific, as do the strings in the “big tune”. Fischer’s pacing is a little more erratic here, though, and less satisfying. The moment where the final stop in the coda is pulled out, for example, and the energy kicks into overdrive, feels matter-of-fact rather than exciting. It’s nowhere like as galvanising as Herbert Blomstedt’s recent Leipzig recording, and there isn’t as much overall punch as you’d get from, say, Chailly. However, it’s still a tightly constructed reading with very good orchestral sound, so it holds its own.

The problems of pacing and drive return more troublingly in the fourth symphony, however. The first movement feels too slow to my ears, the energy levels drooping badly. It feels as if Fischer has taken his foot off the gas and is letting the symphony power by on its own steam, and it’s the only place in the set where I missed the faster speeds of the more period-influenced performances. Out of all of them, it’s this symphony that needs a firm hand at the wheel to control the pacing and drive the musical argument forwards. It seemed at first that the finale was going to provide that, and the opening variations feel tight as a drum; passionato indeed. However, the slower variations drag the pace down far too much. The meandering flute solo is pleasing enough, but that whole sequence feels much too enervated. Things pick up in the later, faster sections, but by then the damage has been done. The scherzo has energy enough, and the slow movement proceeds with stately grace, the cleaner violin tone making a big difference to the sound, but this is too variable a performance to be happily recommended.

Symphony No. 2 is, on balance, the most satisfying performance in the set. That’s mainly because Fischer understands that while this is Brahms’ most “nature-influenced” symphony, it’s nature with a dark tinge as though, to paraphrase Stephen Johnson, it’s taking place in a dark, sinister corner of the forest. The overall sound for the first movement is remarkably silky and smooth, very alluringly so in the lower strings’ opening downward slide, and the set piece moments like the first appearance of the second subject sound like a showcase in great orchestral style. Fischer allows turbulence to intrude on this tranquillity, though, not only in the first movement but also, even more strikingly, into the serenity of the slow movement, where there is genuine emotional churn both in the central section of the movement and at its end. After this, the third movement sounds sparky and light, while the finale has a helter-skelter energy to it that’s entirely fitting.

Symphony No. 3 also takes off with tremendous emotional energy, tearing its way down the scale of the opening theme and working up an invigorating head of steam as it progresses, while finding some (brief) space for reflection in the second subject. As I’ve alluded above, one of the most characteristic things about the orchestral sound across the cycle is the leanness of the string texture. It isn’t quite what you’d call “period style”, but they sound as though they’re playing with only a little vibrato, which adds cleanness and air to the texture. That’s most noticeable in the famous third movement of this symphony, where the sound of the cellos and violas throbs and flows much less than you might have heard elsewhere but, perhaps surprisingly, sounds even more autumnal as a consequence. It’s the winds who twinkle most effectively in the slow movement, however, and the pacing of the finale is very successful, the opening sounding as if it’s gently revealing a secret before the main section takes off like a firework before settling down to a very pleasing sense of mystery in its coda.

The other items in the set are all well played, though I admit I’m a little clueless as to how far they fit into Fischer’s vision of Brahms from an eastern European perspective. That’s partly the fault of the bizarrely whimsical booklet notes, which say very little about anything. Furthermore, each disc gets only a paragraph which, I assume, is a lot less than when they were originally released. Consequently there’s nothing meaningful to learn from them about Fischer’s vision, which feels like a pretty poor own goal from Challenge. The Hungarian Dances, for example, all sound perfectly good, but I wish the notes had said more about why Fischer chose the ones he did.

As for the bigger items, the Haydn Variations sound pert and distinguished, the sound gleaming in places, like the music is really pleased with itself. Each variation has its own very distinctive colour yet, remarkably, coheres into a whole work, turning it into a treat for the ears. The Academic Festival Overture is excitingly played but doesn’t quite hang together, mainly because Fischer pulls the tempo around as if to draw attention to each individual tune distinctively. The Tragic Overture, on the other hand, sounds tight and well organised. The second Serenade shows off the Budapest winds very impressively but, again, I was a little baffled as to what it’s doing in the set. Why not the first serenade, for example?

So much about this set is very good, and the orchestral playing is never less than excellent; but it didn’t hold me completely gripped, and that’s not good enough to give it a place at the Brahms top table, even among more recent digital sets. This is, after all, one of the central symphonic cycles of western music, and almost every major conductor has had a go at recording it over the last century. One of them, tantalisingly, is Fischer’s brother, Adam, but I haven’t heard anything from his set, released by Naxos in 2022. My overall favourite cycle is still Karajan’s set released in 1978, currently available in a very cheap edition from Deutsche Grammophon. For interpretative authority it’s hard to beat, and it also sounds phenomenally exciting in places. Amongst more recent sets I remain unconvinced by the fast, more period influenced sets from Mackerras, Harnoncourt and Ticciati: what they gain in clarity is lost in terms of majesty and vision. If you’re looking for a recent digital set then it seems rather unfair that the two best ones have both come from the same orchestra: the unimpeachable Leipzig Gewandhausorchester, conducted by Chailly in 2012-13 and Blomstedt in 2019-21. They take the music to what feels like the pinnacle of what it can be, and they don’t have an interpretative point to prove. It’s those cycles, not Fischer’s, that I’ll still be listening to in decades to come.

Simon Thompson

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

Symphony No. 1

Symphony No. 2

Symphony No. 3

Symphony No. 4

Variations on a Theme by Haydn

Academic Festival Overture

Tragic Overture

Serenade No. 2

Hungarian Dances Nos. 3, 7, 11 & 14

Instrumental Folk Music from the Region of Sic.