Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

The Complete Symphonies

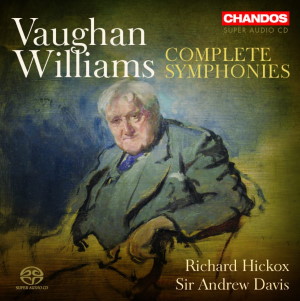

Susan Gritton, Rebecca Evans (sopranos), Gerald Finley (baritone)

London Symphony Chorus, London Symphony Orchestra/Richard Hickox (1-6 & 8)

Mari Eriksmoen (soprano)

Bergen Philharmonic Choir, Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra/Sir Andrew Davis (7 & 9)

Also includes reflections and interviews with Vaughan Williams, Sir John Barbirolli, Sir Adrian Boult, Ursula Vaughan Williams

rec. 1997-2017, various locations

CHANDOS CHSA5303(6) SACD [6 discs: 427]

Sarah Fox, Sophie Bevan, Katherine Broderick (sopranos), Roderick Williams (baritone)

Schola Cantorum, Ad Solem, Hallé Choir, Hallé Youth Choir

Hallé Orchestra/Sir Mark Elder

rec. 2010-2021, various locations

HALLÉ CDHLD7557 [5 CDs: 366]

It’s a poor reflection on me, I know, but when I heard of the death of the conductor Richard Hickox in 2008, my first thought was “that Vaughan Williams cycle will never be finished now”. I’d got to know the symphonies of Vaughan Williams in 2008 during the commemorations for the 50th anniversary of the composer’s death, and Hickox’s Chandos recordings had been touchstones. Very sadly, he died before the cycle was finished so, after a respectful hiatus, Chandos brought in the finest imaginable replacement in the form of Sir Andrew Davis. We’ve reviewed most of its previously issued instalments here on Musicweb.

So the whole cycle is now released for the 150th anniversary of the composer’s birth, and I was really excited to hear how it would hang together. It comes, however, at the same time as the completion of Sir Mark Elder’s cycle with his own Hallé orchestra, and I listened to them both together. They’re fascinating to compare and both are very strong indeed. I’d expected that, due to my previous attachment to it, the Chandos set would sweep the board but, in the event, the plaudits between the two sets are more evenly balanced than I would have imagined.

The first thing that surprised me was the quality of the recorded sound. I’d expected that the Chandos performances, mostly recorded in carefully controlled studio settings, would be uniformly more full and satisfying than the Hallé ones, which were mostly recorded on the wing in live performances. In fact, however, the honours are much more evenly balanced, and even tilt in the Hallé’s favour at times. Take the Sea Symphony, for example. The Chandos sound is satisfying enough, but the Hallé sound is even crisper, the instrumental colour gleaming, the tuttis shining, the adrenaline rush of the opening swooping with raw clarity. The two performances of the symphonhy are fairly similar, though Hickox makes more of the all-important climax on “O thou transcendent” in the finale. Otherwise they are fairly evenly matched in terms of the singing and the orchestral playing. Soprano soloists are similar, too, and both Roderick Williams (Elder) and Gerald Finley (Hickox) bring uniquely different perspectives (and excellent inflections in their delivery of the baritone role. I think I was won over by the surprise of how good the Hallé performance was, however, and I very slightly favour it, though there isn’t much in it.

The sets’ biggest point of difference comes with the London Symphony. Here you’re not comparing like with like, because Hickox gives the “1913 version”, before the amendments that Vaughan Williams made for the published edition, while Elder gives the more standard one. This isn’t the place to reproduce an analysis of the differences: these reviews have already done that very well. Suffice it to say that Hickox is, as far as I’m aware, the only recording in the catalogue to use this version so if you want it then it’s him or nothing. Maybe it’s because I’m so used to the more frequently performed version that I leaned a little closer to Elder, though it’s also because the sense of energy and orchestral punch is that little bit keener. The orchestra explodes into life with a little more punch than Hickox’s, and the Hallé recording puts a sheen on the climaxes that Hickox’s doesn’t. Conversely, the great, swelling string climax of the slow movement sounds more subtle and finessed than Hickox’s, and the mysterious ending shimmers, if anything, that little bit more clearly; like the end of Holst’s Saturn with a little more breadth. Hickox doesn’t manage this, but he does have a wonderful sense of quiet grandeur to his performance, a sense of a great beast of a city gently uncurling itself. The great orchestral climaxes of the outer movements sound terrific, but every bit as impressive is the quiet swell of the slow movement, with its awakening into life sounding like the sound coming out from behind a cloud, and the instrumental solos from the horn and cor anglais are terrific, too.

The honours are a bit more evenly distributed in the Pastoral Symphony. There’s a lot of moderato in this symphony, but both conductors embrace this and build a sound picture of peaceful openness, notwithstanding the symphony’s wartime context. Hickox’s performance builds to a fantastically beautiful performance of the finale, with string tone so honeyed and beautiful that it will make you melt. Hickox also has the better soprano contribution: Rebecca Evans’ vocalise sounds simultaneously beautiful and sinister, giving an edge to the gorgeousness, and seeming to end the music on a question mark rather than a full stop. Sarah Fox sounds much less attractive for Elder, and her acoustical placing is noticeably more awkward. Hickox’s studio sound is a little lighter than Elder’s, and the prominence of the bass in the Hallé sound is notable, but both are admirably balanced and rounded.

I much preferred Hickox’s performance of No. 4, however. Both performances are extremely well played, but Hickox’s has noticeable extra volts of energy that Elder’s never quite finds. Elder comes into his own in the bite of the finale, but Hickox keeps a sharper edge of tension through all four movements, including a wonderfully sinister slow movement that made me think of Shostakovich, so masterly is its pacing and shape. The sharpness, maybe even the savagery of the outbursts in the last two movements is extraordinary, and it builds to an unanswerably final conclusion.

Listening to the symphonies as a chronological cycle, the most striking tonal difference comes in moving from the emotional maelstrom of the Fourth to the soft-focused beauty of No. 5. Hickox immerses you into its inviting sound as if you’re entering the most welcoming warm bath. Once the first subject is left behind, however, a diaphanous shimmer enters the music that serves as a lead into and contrast with the movement’s more urgent central section, and that diaphanous energy returns with a vengeance in the Scherzo. Hickox seems determined to disprove the old belief (now, surely, completely discredited) of Vaughan Williams as the master of the cowpat school who could only do one thing, but he manages this without short-changing us of any of the moments we love, such as the wonderful chorale-like moment at the climax of the first movement, or the unspeakably gorgeous cor anglais solo in the Romanza. This movement’s climax, with ripe strings and singing horns, is terrific, and its transparency is a tribute to the Chandos engineers. The finale is sublime, too. Next to Hickox, Elder sounds as if he’s on auto-pilot. Everything is there: it’s just not nearly as engaging, and Elder’s sound isn’t as rich or as welcoming either.

Hickox’s reading of No. 6 is a thriller. The opening feels like a headlong rush to the precipice, the sense of barely contained anarchy also infecting the chaotic dance of the second theme. The second movement has a terrible (wonderful!) sense of threat to it, like an ominous machine approaching from the distance, captured wonderfully in Chandos’ sound. The hard-driven Scherzo gives no quarter, and a ghostly chill settles over the finale while retaining just enough lyricism to give it humanity. Elder’s performance is also very good and shares a lot of Hickox’s characteristics, but it’s a little more careful in comparison, as though he is paying so much attention to the inner architecture that he has missed some of what makes the music red-in-tooth-and-claw. There is swing and zest to the Scherzo, and to the second part of the first movement, but not as much white-knuckle intensity. He does adopt a much faster tempo for the second movement, however, which injects an even greater sense of sinister encroachment than Hickox evokes. Both performances end on a wonderful note of inconclusive suspension.

Hickox’s involvement with the Chandos cycle ended with Symphony No. 8, a really lively, enormously enjoyable performance. The twinkle and shimmer of the outer movements sounds great (“all the ‘phones and ‘spiels” in the composer’s phrase), while the inner movements sound so different that they might be from a different work. The third movement, for strings alone, has a whiff of the English pastoral to it, while the semi-Orientalist wind bluster of the Scherzo sounds almost Turandot-ish. Elder’s performance slightly has the edge, however. His first movement sounds gleaming and sunlit, light and humorous in a way that Hickox misses, and he even seems to enjoy the galumphing section towards the end. The second movement is tightly wound, while there’s a wonderful expansiveness to the slow movement, the Hallé strings summoning a gorgeous, nutty quality to their sound. What’s more, the finale is an absolute riot, a tremendous celebration of life, and the final clatter of tuned percussion is almost indecently joyful.

Andrew Davis stepped into the Chandos cycle for Symphonies Nos. 7 & 9. He’s every bit as gifted an interpreter of Vaughan Williams, and his contributions are really excellent. I’ve never admired the Sinfonia Antartica as much as many other commentators: to my ears there’s an awful lot of devastation-in-the-face-of-unyielding-nature and not an awful lot else. Consequently, it’s a little difficult for me to get excited about the interpretative differences. I recognise, though, that Elder’s secret weapon is his recorded sound, which is great. The tuned percussion, in particular, sound terrific, and the vocal effects are well managed so that the whole thing fits together brilliantly in the soundscape. The climax of the work comes in the ice falls of the third movement: Elder engineers a tremendous sense of build to this, and the entry of the organ feels like a culmination rather than a moment of bathos, as it sometimes can. Similarly, it’s to Elder’s credit that the oboe and cor anglais solos that launch the subsequent Intermezzo sound built into the texture rather than incongruous add-ons.

So Elder’s performance is very good, but Davis’ is even finer. His control over the opening is nothing short of awesome. He gives the music an extraordinarily ominous feeling of something awesome shifting in the depths. That sense of threat is there right from the beginning, more so than in the Hallé performance, and that comes back with consuming intensity in the finale. The ice falls climax is even stronger for him than for Elder, with an organ sound of almost demonic power, and the Norwegian orchestra bury for ever the idea that only British orchestras can play Vaughan Williams effectively. There is mischievous sparkle to the music for the penguins and whales, and the lyrical music for the Intermezzo carries a beautiful lyrical shimmer. Davis unarguably sees this as a symphony, not as glorified film music, but the element of the cinematic sweep is still there, and he puts it to tremendous purpose to serve the work’s musical and dramatic power.

Davis also comes up trumps in the other direct point of comparison: Symphony No. 9. He gives the outer movements a feeling of grandeur and majesty that isn’t a million miles away from the outer movements of the Sinfonia Antartica, but much less chilly and threatening. This is the grandeur of rolling green hills, a homespun majesty that’s impressive but not intimidating. The exotic instruments, particularly the saxophones, give those movements a particularly distinctive colouring, and Davis lets that shine through in the second movement’s flugelhorn music, too, a feature that grabs the ear but doesn’t dominate. Elder’s performance is a little less subtly drawn than Davis’. The phrasing is big, and the colours are all primary, though that’s something that will appeal to some listeners. He does score with the momentousness of the bells in the slow movement – whether they’re really a reference to Tess of the d’Urbervilles isn’t a question for here – but he underplays the lumbering dance of the Scherzo, which is a shame next to Davis’ high-energy rendering.

So we have here two very highly accomplished sets of the Vaughan Williams symphonies, either of which any listener would be happy with. I was first introduced to these wonderful works through Hickox’s recordings so, as I said, I have special affection for those. Since then I’ve heard and loved, for different reasons, the cycles from Boult (his later EMI one) and Vernon Handley, both of which are also great. I haven’t heard other famous cycles by Thomson, Previn or Haitink, so this review cannot be comprehensive. What I will say, though, is that, if forced to make a judgement between the two sets here, I’d come down on the side of the Chandos one. They’re consistently the more satisfying performances, though it’s a much closer run thing than I had expected it to be, and if I only had Elder’s set then I’d still be very happy.

A few little things: both booklets are very similar because Michael Kennedy’s erudite programme notes form the backbone of both, and both use the same essay for some of the symphonies. Both sets include the full texts of the Sea Symphony, as well. It’s a shame, though, that Chandos didn’t see fit to re-release the “extras” that accompanied the symphonies in their original releases. These include a cracking G minor mass, some orchestral miniatures including the two Norfolk Rhapsodies, and Davis’ wonderful Job. However, Chandos does provide its own filler in the form of some interviews and commentaries from Vaughan Williams himself, as well as Barbirolli, Boult and Ursula, the composer’s widow. In truth, there isn’t an awful lot in any of these, beyond a couple of diversions, though Boult has some interesting things to say about the symphonies’ reception abroad. They’re probably once-only-listens, though, and I can’t imagine them swinging anyone towards the Chandos box. The Hallé box includes only the nine symphonies. Both sets are packaged in clamshell boxes with slimline cardboard sleeves. Neither contains any plastic, if that’s important to you.

It’s wonderful to be able to have so many complete sets of Vaughan Williams symphonies on hand now, something we should widely welcome, and it’s great that the composer’s anniversary gave these two labels the excuse to issue these sets. It’s only a shame that we still need to work so hard on our friends outside of the UK to get them to appreciate this music as much as we do!

Simon Thompson

Previous review (Hallé): Nick Barnard (June 2022)

Help us financially by purchasing through

Chandos

Hallé