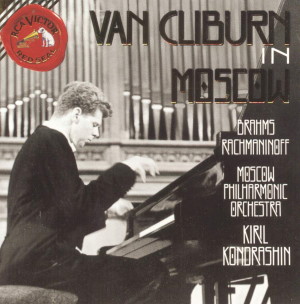

Van Cliburn in Moscow

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op 43

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Piano Concerto No 2 in B-flat, Op 83

Van Cliburn (piano)

Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra/Kiril Kondrashin

rec. 1972, studio (Rachmaninov) & live (Brahms), Moscow Conservatory. ADD

Presto CD

RCA 09026626952 [76]

The American Van Cliburn’s links with Russian culture were strong and he was lionised as much in the Soviet Union as he was feted in his home country. These recordings of the Paganini variations and the Brahms piano concerto were made under studio conditions and in concert respectively in the Moscow Conservatory, in collaboration with the same Russian conductor, Kiril Kondrashin, who had led the Moscow Philharmonic in the first International Tchaikovsky Competition fourteen years earlier in 1958 , which, of course, Van Cliburn won. Most collectors will have come to know both the pianist and the conductor here through the RCA recordings of their Carnegie Hall performances later the same year of the Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 3 and the first Tchaikovsky piano concerto.

The soloist in the Rhapsody comes across very clearly but the sound in general is wiry and clangourous, with some faint hiss, and the orchestra is a rather remotely recorded, making the partnership somewhat one-sided and imbalanced. The weight of Cliburn’s left hand comes through but there is also an element of distortion about the loud passages and I would not say that this is anywhere near as good the best analogue recordings of that era. Regarding the musicality of the performers, however, I have no reservations; this is a thrilling account, wild, free, Romantic and wholly absorbing, combining leonine strength with poetic sensibility. The Big Tune of Variation XVIII is lovingly rolled out without schmalz but again, the comparative recessiveness of the orchestra lessens its impact. Nonetheless, the precision and power on the part of both piano and orchestra in the last two variations leave an indelible impression.

The immediately noticeable hiss and ambient noise in the Brahms concert recording are at first a little off-putting, but the sweep of Cliburn’s playing soon compensates and here the balance between soloist and orchestra is much more even-handed; the clattery element which mars the Rhapsody is absent, too – strange, given that it was studio-made and this is live. As the performance unfolds, however, it becomes apparent that neither the soloist nor the orchestra sounds especially inspired here; it might perhaps be because the remastered Moscow tapes sound is a little dull, but I am not as engrossed by this as I am by Cliburn’s recordings of the other major piano concertos mentioned above. His playing is, of course, often magisterial but inspiration and a sense of rapport between conductor and soloist seem in short supply – which, again, is peculiar, given the history of their relationship. I will give an example: five minutes into the Allegro appassionato second movement Scherzo Brahms introduces a stormy, 6/8-time trio section which is like the swinging of great bells, and it should thrill the listener but here falls flat. The Andante comes across much better; showcasing Cliburn’s delicacy, but even if elsewhere there is very little audience noise, some coughing in the quiet moments in this movement is irritating. His dexterity and rhythmic flexibility in the finale are delightful and Kondrashin, too, sounds more animated.

As a souvenir of Van Cliburn demonstrating his special gifts on an historic occasion, these recordings are valuable, but if you are desirous of hearing Cliburn play these particular works masterfully, I suggest that in terms of both sound and performance his 1961 recording of the Brahms with Reiner and the Paganini variations with Ormandy are preferable. My own favourites reman Rubinstein in the Variations and Zimerman with Bernstein for the Brahms.

Ralph Moore

Help us financially by purchasing through