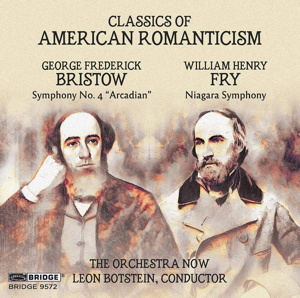

Classics of American Romanticism

George Frederick Bristow (1825-1898)

Symphony No. 4 Arcadian Op. 50 (1872)

William Henry Fry (1813-1864)

Symphony No. 5 Niagara (1854)

The Orchestra NOW/Leon Botstein

rec. 2022, Bard College, New York, USA

Bridge 9572 [55]

Fulfilling the CD title of “Classics of American Romanticism”, these two works are blossoms of mid-late nineteenth century romanticism. The two composers in question are practical and idealistic upholders of the United States’ home-grown art. They are of that generation whose blooms pre-dated those of Paine, Chadwick, Hill and Loeffler. Of Bristow and Fry’s brethren only that well-travelled Jullien-style showman, composer Louis Gottschalk, continues to have any sort of celebrity profile.

During the 1960s Karl Krueger’s Society for the Promotion of the American Musical Heritage launched and sustained the Music in America LP series. It held a torch for Bristow and Fry among many other later figures. Indeed, in 1967 Krueger and the Royal Philharmonic recorded this Bristow symphony – titled as The Arcadian or Pioneer – (MIA 134) but with what have now been identified as “large cuts in the first and last movements, reducing the length of the piece by at least ten minutes”. Bridge have released CD reissues of considerable swathes of Krueger recordings (Coerne; Farwell) but never got to Bristow and have now forsaken the series.

Bristow was Brooklyn-born and was much associated with the young New York Philharmonic. There are five symphonies of which we can hear Symphony No. 2 in D minor, (“Jullien” after showman conductor Louis-Antoine Jullien (1812–1860)) (1856) (MIA143 and New World Records, 80768-2) and Symphony No. 3 in F-sharp minor, op. 26 (1859) (MIA144 and CHAN9169). Very much in the then-contemporary orthodoxy of practice, Bristow unwisely, gave titles to each of the four movements of his Arcadian Symphony. This makes them ‘read’ as if a linked sequence of sepia tone poems:- I. Emigrants’ Journey Across the Plains; II. Halt on the Prairie; III. Indian War Dance (a title that might seem to link with composers in the Indianist tradition, like Arthur Farwell) ; IV. Finale: Arrival at the New Home, Rustic Festivities and Dancing.

Bristow’s first movement is braw, with a self-effacingly gentle solo violin start. There’s then a gathering of traction and tension. It is as if Bristow, moderating blessing and innocence, is pitching towards the opening of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto. The violin solo returns at 9:15. There is a bustling-hustling firebrand echo of young Parry’s admirable First Symphony (Nimbus) at 4.50. The second movement reeks, in a dignified way, of a riverside prayer meeting. This cools the blood after the stirring first movement. There’s some subdued Wagnerian brass writing which in this case has a hint of a cornet in the mix. In the next movement there is more excitable champagne playing from the flute and the other woodwind as well as some noble brass. Given the title it is not very fierce; indeed, the composer who comes to mind is Ketèlbey in his chirpy Persian mood. The gallop and surge of the finale culminates in a dark peroration which at times shakes off the conventional. Vigorous Tchaikovskian painting of mood and colour is not for Bristow; that is for the likes of the enduringly gifted Edward Macdowell. The effect is comparable with works that, through their titles, suggest dramatic impressionism but deliver something flatter and more classical such as the Ocean Symphony of Anton Rubinstein and the Sea Symphony of Danish romantic Haakon Børresen. The Bristow, which is good-hearted and at times brilliant, will appeal to those with a soft spot for Dvořák and an empathy with Schumann, Mendelssohn and Stanford.

The shorter-lived William Henry Fry was a stalwart advocate for composers of the North American continent. This son of Philadelphia wrote seven symphonies, all named. His 1854 Niagara Symphony is a showpiece à la 1812. It reportedly sports eleven timpani. Dramatic contrasts of silence and volume are said to evoke the spectacle of “the falling waters”. A pictorial piece, it opens with a rumbling crescendo fronted by the timpani but gradually made the more emphatic by the whole orchestra. In what turns out to be a recurrent feature, the brass blazon what sounds like a fragment of a hymn of the Republic. Fry‘s Lisztian tempest swirls and whirls in a credible evocation of a tornado bearing down. Riven by thunder-bolts, the music glooms away but the sun breaks in at 5:17 with the same sort of prayer meeting hymn hinted at in Bristow’s Halt on the Prairie. The skies again become angry and filled with thunder and lightning. In terms of playing it’s no epic: the whole thing is done and dusted in less than thirteen minutes.

If you need to focus in on Fry then you are in luck. There’s a thoroughly well tricked-out Fry Naxos disc to reward your curiosity. Many years later Ferde Grofé – also a sucker for spectacles of nature – wrote a Niagara Falls suite. The spell continued and resurfaced in Michael Daugherty’s 1997 windband piece of the same title.

This Bridge disc delivers muscular recordings. It also includes wind playing of astonishing elation. Although a little more of the same spumante is needful from the strings they sound involved and well blended. The CD’s documentation is a cut above in the form of an extended essay in English only by Kyle Gann.

Here are two rare symphonies from the traditions of early American romanticism. They are heard here delivered with golden age verve rather than as dutifully played museum exhibits.

Rob Barnett

Help us financially by purchasing from