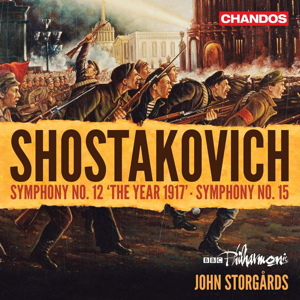

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Symphony No.12 in D minor Op.112 ‘The Year 1917’ (1959-61)

Symphony No.15 in A major Op.141 (1971)

BBC Philharmonic/John Storgårds

rec. 2022, MediaCityUK, Salford, UK

Chandos CHSA5334 SACD [85]

One of my sorrows as a music collector was that Chandos were not able to complete the cycle of Shostakovich Symphonies they started recording with Neeme Järvi and the (then) SNO. From the early/mid 80’s for about five years this team made discs of Symphonies 1-10 (excluding the vocal Nos. 2& 3). These come from the rich vintage years of Järvi’s initial series of recordings for the label. What is all the more remarkable is how nearly all of these performances – some nearly forty years old – have remained at or near the top of the pile of finest versions both interpretatively and techniquely. Järvi completed the cycle for DG in Gothenburg with less compelling results and Chandos has, in a rather patchwork manner, likewise sought other artists to explore this repertoire. The truth is none of those alternatives have matched the blazing intensity of the playing or the thrilling power of the engineering of those earlier recordings. Chandos have now passed the Shostakovich baton to John Storgårds and the orchestra of which he is the current principal conductor; the BBC Philharmonic.

This is the second release after Symphony No.11 ‘The Year 1905’ which was recorded in August 2019. Three years later Storgårds has returned to the studio for the other pictorial/revolutionary symphony – No.12 ‘The Year 1917’ coupled with the ever intriguing and elusive Symphony No.15. The result is an exceptionally generous disc running to 85:01 recorded in Chandos’ sophisticated 5.0 SACD sound – I listened to the SACD stereo layer. The disc opens with a rather disappointing performance of the Symphony No.12 in D minor Op.112 ‘The Year 1917’. Many critics and listeners dismiss this work as the composer’s “worst” symphony – thin on musical material and inspiration. That might well be the case but playing it in a manner that emphasises those potential shortcomings hardly makes for a compelling listening experience. Whether Shostakovich’s heart was in the work or not the result is the gaudy musical equivalent of agitprop and as such it needs a performance of reckless dangerous fervour, harsh extremes and primary colour playing. Here we get the ever-urbane and cultured BBC Philharmonic playing quite beautifully but with no danger at all. Storgårds’ interpretation is safely centrist – timings and tempi are unremarkable. The ending of this symphony is laboured, repetitive and indeed crude – I do not want a performance to remind me of those ‘failings’ quite so successfully as this one does.

There is an argument that this is the kind of music – and the message behind the music – that you need to be Soviet/Russian performer to ‘get’. So considering some other SACD versions both Dmitri Kitajenko with the Gürzenich-Orchester Köln and Oleg Caetani (Russian by parentage) with the Sinfonica di Milano Giuseppe Verdi generate the hysteria, menace and violence that pervades much of the score. The Chandos SACD engineering has a slight sense of detachment that characterises some of their recordings but it is very good on rich detail precisely managed. Percussion mutter dangerously, the bass drum is given an almost overbearing presence. If there is a lack of string bite and overwhelming weight of tutti orchestral tone I suspect that is an accurate reflection of the sound in the studio rather than a shortcoming of the engineering. Returning to a relatively recent Russian performance (albeit in standard CD format) – from Alexander Sladkovsky and the Tatarstan National Symphony Orchestra – it is possible to hear just how dramatic and absorbing this work can be. The engineering is not a patch on this new Chandos disc and indeed the Tatarstan performance starts off in a rather muted fashion both musically and technically. But out of the murk rolls a terrifying and implacable juggernaut – one of those nightmarish orchestral passages that Shostakovich perfected. Timings here do tell a story – Sladkovsky a full minute quicker in the opening Revolutionary Petrograd, a weighty three minutes slower in Razliv, just a handful of seconds quicker in Aurora and identical in the closing Dawn of Humanity. Even in that latter movement the Tartarstan players – with distinct echoes in their collective sound of their Soviet heritage – manage to make the empty rhetoric of the closing pages rather epic. In contrast Storgårds sounds as if there is nowhere to go except round and round.

Symphony No.15 in A major Op.141 fares considerably better from this rather detached objective style and the detail of the remarkable orchestration is beautifully apparent in the SACD engineering. Again this is a rather straight-faced interpretation – not withstanding a beautifully pensive cello solo in the second movement Adagio and burnished brass playing throughout – the Siegfried’s Funeral Music quotation is quite beautifully played and recorded here. Other performances underline the subversive character and make more of the big climaxes when they come not just in dynamic terms but in terms of the meaning behind the musical gesture. It could be argued that this is the first objective symphony Shostakovich wrote since No.4. All the others have texts, or programmes or implicit critiques of the State. Various descriptions from toyshops to premonitions of death have been given to the work but I suspect it is as much as anything the composer’s personal testament in music.

Mark Wigglesworth’s SACD cycle for BIS with various orchestras has been greatly admired. Certainly they are beautifully played and recorded but in this Symphony I find him to be even more detached than Storgårds. Maxim Shostakovich’s recording with the Moscow Radio SO in 1972 has an urgency – even a haste – that I am not sure any version has matched since. Certainly it changes the mood of the opening Allegretto from toyshop bonhomie to something far more unsettling. But returning to this new recording, in its chosen performing style it is very well done and the engineering copes very well without the wide dynamic range from the pained climax in second movement through to the remarkable closing bars of the work with the life-support percussion chattering away into silence over the held A major string chord. This is always an astonishing passage and it is recorded and performed here as well as it ever has been.

The Chandos production and presentation is reliably good. The booklet essay (in the usual three languages) by Shostakovich expert David Fanning is informative beyond the usual factual/analytical manner. The detailed engineering is excellent at revealing the subtlety and variety in these scores – yes, even in Symphony No.12 – and I suspect where there is a lack of bite and ferocity this reflects the performance rather than being a ‘failing’ of the recording. For all the qualities it exhibits this will not be a version of either work I would seek out before pre-existing favourites.

Nick Barnard

Help us financially by purchasing from