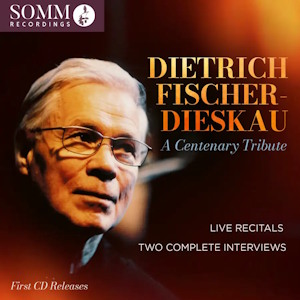

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (baritone)

A Centenary Tribute

Gerald Moore, Irwin Gage, Karl Engel (piano)

London Symphony Orchestra/ Zoltán Kodály

rec. live, 1960-71

Texts and translations included

SOMM Ariadne 5038-2 [2 CDs: 145]

People throw around the word ‘legend’ casually these days. It can be applied willy-nilly to a footballer with a couple of caps or an actor with at least one film to their name. But it would not be inappropriate to apply it to Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, born in Berlin exactly 100 years ago this May 28th, the greatest of all baritones, and, in my humble opinion, the greatest singer of the 20th century. DFD was blessed with a sublimely beautiful voice, but to be a great singer is so much more than to have God-given vocal qualities. He also had a deep understanding of the words and the music of everything he sang, and the ability to convey this to his audiences. Then there is his unsurpassed mastery of all the major areas of repertoire: recital, opera, oratorio. It all makes him a shoo-in for the title of greatest singer of the past hundred years – certainly the greatest male singer.

Disc 1 brings us extracts from four concerts. At the Royal Festival Hall in London in 1962, accompanied by the great Gerald Moore, DFD performed Feruccio Busoni’s four superb songs, amongst them a setting of the Song of the Flea from Goethe’s Faust, and a Gypsy Song, Zigeunerlied. Both show how Fischer-Dieskau enjoyed the bizarre and the grotesque, and projected them brilliantly. He had, by that time, learned how to get an audience eat out of his hand!

The second group comes from a recital at the Helsinki Festival in 1971. In addition to gentle, thoughtful songs by Richard Strauss (Gefunden) and Max Reger (Einsamkeit), the singer included music by composers who, I must admit, were hitherto almost unknown to me. Anna Amalia – the Duchess of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach and a niece of Frederick the Great – devoted her life to her musical pursuits, despite heavy official duties. The setting of Goethe’s Auf dem Land has an attractive melody of touching simplicity.

Johann Friedrich Reichardt’s Beherzigung is bold if unremarkable. Carl Friedrich Zelter’s Gleich und Gleich, genuinely charming, tells the simple story of a little flower and the bee that sips its nectar. Zelter was an almost exact contemporary of Franz Schubert. The song comes from the same cultural stable as Heiden Röslein or even Die Forelle, and is none the worse for that. (Never mind that it is said that he and Schubert had very little time for each other!)

The third group, recorded at the Royal Festival Hall in 1970, finds the singer on slightly more familiar territory: six Mahler songs. The first three short numbers are from the group of Lieder und Gesänge aus der Jugendzeit (Lieder and Songs of Youth), written around 1892. Fischer-Dieskau brings out delightfully the rustic humour of the first two, while the third, Selbstgefühl, gets a laugh and a well-deserved round of applause.

Three of five Rückert-Lieder – from ten years or so later – come next. They show how far Mahler’s musical style had moved on. Fischer-Dieskau sang the orchestral versions of all five songs seven years earlier, with Karl Böhm and the Berlin Philharmonic; it still is one of the greatest recorded performances of these songs on disc. But here, especially in Um Mitternacht, there is, if anything, an even stronger intensity and grandeur of expression. One feels that he is giving everything he has, and it is very moving. It is a great pity he sang only three of the songs, and did not include the greatest of them all, Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen.

We owe the last group to a remarkable Royal Festival Hall concert in 1960, where the young baritone sang with the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by the great Hungarian composer Zoltán Kodály (he was then 78 years old). They performed three of Kodály’s orchestral songs. I have not heard them before, but they were my highlight of the programme. The first song, A közelítő tél (The Approaching Winter), has a remarkable instrumental prelude, which at first reminded me of Delius’s Brigg Fair,and then opens out into a deeply expressive lament. Sirni, sirni, sirni is similarly a meditation on the approach of death, but with an added edge of bitterness. Fischer-Dieskau captures all of this, and communicates with the utmost emotional empathy.

The final song, Kádár Kata – more of a dramatic scena in 15 minutes – is a revelation. Kodály wrote it originally for a music theatre piece called Székely fonó (The Spinning Room), and based it on Hungarian and Transylvanian folk material. In the song, a young man confides in his mother, telling her of his desperate love for the girl named Kata Kádár. The mother coldly dismisses his protestations – and, suffice it to say, it all ends badly. In this powerful music, Kodály comes very close to his great compatriot Béla Bartók. It is dissonant, it is expressionistic, yet it has the intervals and inflections of Hungarian folk music.

The whole fascinating compilation serves to emphasise DFD’s wide and various sympathies and interests, and the intelligence with which he approached the words and music of all these songs.

Disc 2 contains Fischer-Dieskau’s two substantial interviews in English with the English music journalist Jon Tolansky. The first was made on the occasion of his 75th birthday in 2000, the second five years later for his 80th. His English was not perfect, but he was very fluent. That allowed him to make numerous interesting and insightful comments about his career, the art of singing, and music more widely. When he discusses the many, many great musicians – conductors, pianists, singers – with whom he worked, he is most perceptive. He gives us small but revealing glimpses of them at work.

Perhaps the most surprising revelation in the interviews is that DFD had always wanted to be a conductor, long before he became a singer. So, he makes particularly interesting observations on the personalities and behaviour of the many great conductors he worked with. Furtwängler, for example, was racked with self-doubt; Klemperer was always terribly nervous before going on to conduct; Ferenc Fricsay, seriously ill in his final years, made all his performers tense because of the pain he was suffering; Beecham was a great ‘improviser’, in that he rehearsed thoroughly but kept surprises for the performance itself. DFD kept his perhaps most cutting remarks for Karajan; he talks about the conductor’s self-aggrandisement through his fast cars and piloting, but has only relatively faint praise for his prowess as an interpreter.

Then there are all the operatic roles he undertook, which he discusses in depth: Golaud in Pelléas et Mélisande; Bluebeard in Bartók’s masterpiece; Verdi’s Macbeth, and Iago in Otello; and of course Hans Sachs in Die Meistersinger. What a career – such breadth and depth!

One might criticise Jon Tolansky for being perhaps too audibly deferential. He does sound at times a little as if he is interviewing royalty. But then, in a sense, he is doing just that. Who among us, with a full understanding of the greatness of this performer sitting in front of us, would not be at least a little bit awe-struck?! For any devoted fans of DFD – in truth, uncountable – these CDs are a must-have, must-listen.

Gwyn Parry-Jones

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Previous review: Dominic Hartley (May 2025)

Contents

Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

Lied des Unmuts BV 281

Zigeunerlied BV 295a

Schlechter Trost BV 298a

Lied des Mephistopheles BV 278a

(Royal Festival Hall, London, 14 May 1962, Gerald Moore, piano)

Anna Amalia (1723-1787)

Auf dem Land

Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752-1814)

Beherzigung (Aus Lila)

Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758-1832)

Gleich und gleich

Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Gefunden TrV 220/1

Max Reger (1873-1916)

Einsamkeit Op.75/18

Ferruccio Busoni

Zigeunerlied BV 295a

(Kulttuuritalo, Helsinki Festival, 6 September 1971, Irwin Gage, piano)

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

from Lieder und Gesänge aus der Jugendzeit

Ablösung im Sommer

Um schlimme Kinder artig zu machen

Selbstgefühl

from 5 Rückert-Lieder

Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft!

Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder

Um Mitternacht

(Royal Festival Hall, London, 6 July 1970, Karl Engel, piano)

Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967)

2 Songs Op.5 (K.34)

A közelítő tél

Sírni, sírni, sírni

Kádár Kata K.127

(Royal Festival Hall, London, 3 June 1960, London Symphony Orchestra/ Zoltán Kodály)

Interviews from 2000 & 2005 with Jon Tolansky