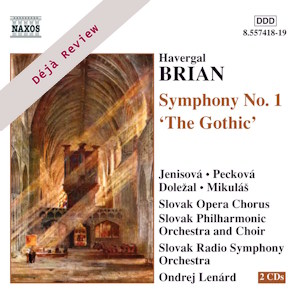

Déjà Review: this review was first published in June 2004 and the recording is still available.

Havergal Brian (1876-1972)

Symphony No. 1 The Gothic (1919-1927)

Eva Jenisová (soprano), Dagmar Pecková (alto), Vladimir Dolezal (tenor), Peter Mikulás (bass)

Slovak Philharmonic Choir, Slovak National Opera Chorus, Slovak Folk Ensemble Chorus, Bratislava City Choir, Lucnica Choir, Bratislava Children’s Choir, Youth ‘Echo’ Choir

CSR Symphony Orchestra (Bratislava), Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra/Ondrej Lenard

rec. 1989, Concert Hall, Czechoslovak Radio, Bratislava, Solvakia

Naxos 8.557418-19 [2 CDs: 114]

That Brian wrote thirty-two symphonies is reasonably well known. Many of these were written in old age.

This is the first and so far the only authorised recording of this Symphony. It was a massive enterprise from the first long-sustained flush of Brian confidence. It crowned the period charted from the composer’s death in 1972 to the end of the Simpson-driven cycle of BBC broadcasts of the symphonies in 1989.

Boult conducted the work in 1966 and this was broadcast on the BBC. Tape machines whirred and by 1978 the Aries company had issued a pirate version of that tape on LP-2601. It was in pretty decent sound too – certainly the best that company ever achieved. There were some abysmal sounding LPs from Aries – try the Aries LP of Brian’s Symphony No. 2 !

In 1980 I travelled to London to hear The Gothic live. Ole Schmidt conducted again at the RAH. It was a shattering experience. Of course there have been other performances including some heroic but amateur efforts. However these were not recorded.

If you must have a historical and cultural nexus for this work then surely it is the Great War. The sometimes crushing violence of The Gothic surely reflects that conflict as well as the long litany of deaths both among the Allies and the Germans. I mention Germany because, like many British composers, (Elgar and Holbrooke are other examples among many) Brian had a great affection for German culture. The war created loyalty tensions in the musical world as much as anywhere.

The notes for this Naxos set, reduced by Keith Anderson from the original Marco Polo issue, are by Brian and Foulds champion, Malcolm Macdonald. The sung Latin texts are printed in full with parallel translations. The work is liberally tracked so that you can follow the structure, incident by incident.

Has there ever been a First Symphony as ambitious in intention, grasp and achievement as Havergal Brian’s Gothic. Of course there have been remarkable firsts; I think of Prokofiev’s and Shostakovich’s works. None of these however have stormed the heavens or stared unblinking at the great philosophical and spiritual issues in the same way as Brian’s symphony. Ambition amongst composers is the needling drive to create. Ambition is not an unusual quality; it is the extent to which it is matched or excelled by mental reach and creative grasp that distinguishes the greatest composers. Brian had both ambition and preternatural ability and this Symphony is the evidence. Across its almost two hours it neither falters nor blinks. Great time-span does not spell intrinsic greatness. It can spell prolixity and garrulous meandering. Brian uses his almost two hours because that is exactly the time-span required to set out his ideas and develop them at every level.

Violence and Peace stand close to each other throughout. Try the last section of the first movement for the pacific voice made eloquent in the solo violin. This is Brian’s reaching for The Lark Ascending. You find a similar tune in the first movement of Brian’s Third Symphony (Hyperion – Helios). For Violence we can cite the Mars-like dynamic established by the rapped-out timpani attack impelling the work forward at the start of the first movement; it’s just one example. That figure is recalled later in tr.15 CD2 where it rises to a crashingly emphatic statement.

The layout of the Symphony some may find disconcerting. However it does work. The first three movements are entirely orchestral. In fact they work as a ‘conventional’ symphony and have been played in that form (I have a tape of Charles Groves conducting a performance of that part of the work in a Crystal Palace concert in 1974). The second part is a massive setting of the Te Deum for multiple soloists, choirs, full orchestra and brass ensembles.

Massive effects are only part of the picture – perhaps the smallest. In the first part of the second movement at 2.38 listen out for the affecting orchestral detailing in the left hand channel. Delicacy is one thing but there is also the racking and scorching pain of the work’s great cortège of death rising to a liberal cargo of dissonance at 5.54.

You may well think of other composers as you listen. For example in the second movement you will encounter a ‘ticking’ figure linking with the snowy ambience of Bax’s Fifth Symphony. Gloriously glowing horns call out above the magnificent din put up by the rest of the orchestra in a piece of music that seems to define heroic on the fly.

I mentioned that you will think of other composers. A further example comes in the first part of the Te Deum where the profound basso depths of the Rachmaninov Vespers are hinted at. This climaxes into a picture of the seraphic hosts streaming across the sky. Continuing this image we can refer forward to CD2 tr. 18 where the suggestion of conflict in the heavens has Satan cast down but not before a great conflict in the skies. This is music that rattles with Hieronymus Bosch horror and awe.

The Judex (tr. 1 CD2) features yet more extraordinary writing. The wheeling choral passage is like Holst’s Hymn of Jesus – itself one of the most extraordinary works in all musical history.

Tr. 2 CD2 has a brutal lumbering march with the sound of raw fanfares and brass bands rolling and echoing around the great space of the Slovak Concert Hall. Once again however Brian leaves us in awe with the Mother Goose iridescent delicacy and joyful glitter of the women’s voices and silvery tinkling percussion (tr. 10 CD2). The mood then switches in tr. 13 to a jaunty, slightly Mahlerian, march for nine clarinets. This is perhaps an echo of the open air values of the hiking movement of the 1920s and 1930s. That very march is carried over into a wordless vocalising that, in its spirited cheeriness, seems to look back to the columns of troops singing patriotic if irreverent songs as they went up to the Front. At other times it might link with pictures of children hiking through the Alps (tr. 14).

The work finds quiet though not placid consummation in words intoned with deep reverence: ‘Non confundar in aeternam’. The singing is rich and resonant in bass definition. Not that Alexander Sveshnikov and the USSR choir would not have made even more of a dream-team ending.

As a recording it is amongst Gunter Appenheimer’s best and of course it was captured in the exemplary grand acoustic of Bratislava’s world-standard concert hall. I have already commented on this extraordinary hall when reviewing the Alexander Moyzes series of twelve symphonies, also on Marco Polo.

Enthused by The Gothic and want to know where to go next? There is nothing like The Gothic but the Second Symphony (on Marco Polo) and the Third (Hyperion, Helios) are similarly grand though much shorter. We await a recording of the Fifth The Wine of Summer for baritone and orchestra (superb almost expressionistic work – think Zemlinsky and Delius). The Sixth is compact but outstanding – possibly the next best Brian symphony but it is still consigned to vinyl perdition on a Lyrita LP (c/w No 16) LPO/Myer Fredman. A case of Prokofiev 6 meets Bax. The other Marco Polos are listed below and are all well worth exploring. However you need to be aware that Brian’s language became more elliptical and gnomic as time went on. There are no miniature Gothics although Symphony No. 22 lasting just over eleven minutes is extremely impressive. The EMI Classics double album of Brian symphonies 7, 8 and 9 is well worth having and is also a good place to go stepping off from The Gothic.

Brian’s Gothic is a massive asseveration of confidence by someone who stood as an outsider to the musical establishment unblessed with private resources or a public school education let alone a formal musical training. It is a work of staggering scale and substance.

Rob Barnett

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free