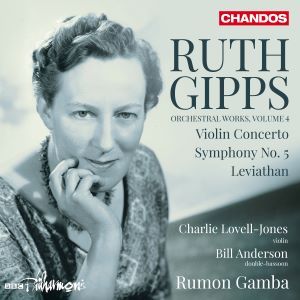

Ruth Gipps (1921-1999)

Orchestral Works Volume 4

Violin Concerto in B flat major Op.24 (1943)

Leviathan Op.59 (1969)

Symphony No.5 Op.64 (1982)

Charlie Lovell-Jones (violin), Bill Anderson (double bassoon)

BBC Philharmonic/Rumon Gamba

rec. 2022-24, MediaCityUK, Salford, Manchester

Chandos CHAN20319 [70]

Between volumes 2 and 3 of this revelatory Chandos survey there was a rather frustrating twenty seven month wait with my reviews appearing here and here. A great cause for celebration is that volume 4 now appears barely a couple of months later. That celebration is heightened by the fact that the excellence of the music is once again revealed in performances and production from Chandos’ very top drawer.

Part of the value of this series – as I mentioned previously – is not down to individual works alone but the cumulative overview of Gipps’ output and style that such a series of discs can provide. Certainly, one thing has become very clear indeed; Gipps was a precocious talent. Other discs have included the beautiful Oboe Concerto Op.20 of 1941 [Vol.2] and Symphony No.1 Op.22 of 1942 [Vol.3] as well as shorter early works. Here we are given the Violin Concerto Op.24 from 1943 – written when Gipps was still just 22. This was written for her (much older) brother Bryan. As an aside – trying to find out what happened to Bryan Gipps online is quite tricky – made all the more confusing by the fact that Gipps’ father Bryan (with a ‘y’) also played violin as did her nephew Bryan – also spelt that way. The result is a substantial – 27:14 – concerto in the three traditional movements with a fairly rhapsodic opening Moderato, a lyrical lovely central Andante with a jigging Allegro finale. There is no cadenza as such and in general terms the virtuosic demands of the concerto are relatively low. That said, it is still very hard to play it as beautifully as it is here by violinist Charlie Lovell-Jones. March’s release schedule has been kind to Lovell-Jones with him debuting two major concerti on Chandos; this work and the Walton concerto alongside John Wilson and the Sinfonia of London. In the latter I found Lovell-Jones’ playing to be technically stunning but overall I felt the work was a little too hard-pressed. In strong contrast, in this Gipps concerto Lovell-Jones has exactly the right rhapsodic and lyrical/ecstatic style.

Gipps was a pupil and disciple of Ralph Vaughan Williams and in many ways this sounds like the major string concerto the older composer never wrote. As I wrote in my review of Volume 3, the older composer is an inspirational presence rather than one whose style and manner is slavishly imitated. For sure when listening to the Symphony No.5 written some 40 years later there is a clear sense that Gipps’ musical voice has evolved into something more individual, but there is so much to enjoy and be beguiled by in this concerto that it seems churlish to point to gestures or turns of phrase that could be considered imitative. There is one area where I did wonder if some kind of musical ‘cross-pollination’ between teacher and pupil had occurred. At the climax of each movement there is a kind of instrumental “alleluia” that reminded me of similar moments of valediction in Vaughan Williams’ Symphony No.5. That work was of course premiered at the Proms in June 1943 having been completed late the previous year. There is no indication in Lewis Foreman’s reliably insightful liner note that the older composer had shown the score to his pupil or she heard that Proms performance. But both works seem to be an expression of belief and faith (not in a religious sense as such). For sure the concerto is a pastorally infused work with a rapturous beauty that no doubt struck a chord in Wartime Britain but equally marked it down as reactionary and conservative in the post-War musical world. The liner states that the work “did not establish itself in the repertoire and was not published”.

Being exposed to a widening group of Gipps’ scores reveals just how assured she was handling a full orchestra even in these student works. Her scoring might not have the striking individuality of her exact contemporary Malcolm Arnold (although Symphony 5 is another matter) but her writing is always effective and attractive. Interesting to note just how often ‘her’ instrument the oboe/cor anglais is given especially gratifying melodic material – quite beautifully played by the BBC PO principals here. As with the earlier discs, great credit must go to Rumon Gamba who seems to naturally understand that this is music that must be allowed to flow and unfold. Of course there are powerful and exciting passages that sound thrilling here but Gipps’ is not a composer of angst or excessive drama. Alongside Gamba, Lovell-Jones pitches his performance perfectly and is helped in this by the Chandos engineering which places him in the orchestral soundstage so his presence is neither inflated nor swamped. For all the passagework that Gipps gives the soloist this is more a case of it intertwining in and around the orchestral textures rather than simply being display grafted onto an orchestral support. There are of course many fine British violin concertos from around this period that have been under-represented on disc – Rubbra, Alwyn, Rawsthorne even the Bax has only had a single modern outing and the Moeran just two and other works of interest still wallow in obscurity. So even within this niche field there is considerable competition, but certainly for collectors interested in the genre, let alone this composer this is an extremely attractive and easily approachable work. For a composer of student age it is very accomplished. I would like to think if performing material for this work becomes readily available it would attract more performances.

Just over a quarter century later Gipps contributed another concertante work albeit for an unusual instrument in the solo role. Leviathan Op.59 for Double-bassoon solo and Chamber Orchestra was written in 1969 for Valentine Kennedy – bassoonist in the London Philharmonic Orchestra. On YouTube can be found a rather murky(!) 1976 performance with Kennedy playing the solo role accompanied by Vernon Handley and the BBC Welsh SO (as was). The work also exists and is published in a version with piano accompaniment. The BBC announcer suggests that the title – “the monster of the deep” simply reflects the contra bassoon’s position as the lowest voiced orchestral instrument. The piece is just 5:02 but is evocative not just a novelty. A central brief dancing section in 5/8 shows the instrument can be more than holding sustained pedal notes although it does start and end “in the depths”. Gipps’ skilful handling of the orchestra is demonstrated both by her effective and interesting writing for the solo part as well as a delicate accompaniment that ensures the solo line is clearly present throughout. The soloist here is the BBC PO’s own Bill Anderson who evidently enjoys his moment in the spotlight.

The highlight for me of this new disc is the discovery of the Symphony No.5 Op.64. With this recording Chandos have completed their survey of the Gipps Symphonies – all have been a genuine delight to listen to but just possibly they have kept the best until last. Four of the five symphonies run for 30-35 minutes. By a handful of seconds this symphony is the longest [37:16] but more significantly it is scored for the largest orchestra Gipps ever deployed; quadruple woodwind, 6 horns, 3 each of trumpets and trombones, 4 percussion and timpani, strings. 2 harps and celesta. Given its 1982 genesis there is something deliberately defiant about such a large old-style Romantic Orchestra. Gipps knew first-hand the implications/cost for ensembles to perform a far from straight forward work written on this scale. The marginalisation of Gipps as composer, performer, educator and conductor post World War II was a scandal – although not a fate she suffered alone – and she fought to be heard and taken seriously for decades. I did wonder whether this was one last thumbing of the artistic nose at the establishment nay-sayers. Lewis Foreman writes that Gipps submitted this work to the BBC for performance but it was rejected by the reading panel of the day – Foreman does not elaborate on any of the reasons that were given. Understandably if unwisely (was the BBC ever going to change their mind….?) Gipps placed adverts in the classified press asking “Why no 5th?” to no avail. I am not clear if Gamba and the BBC PO gave any public performances as part of the preparation for this recording – it not, not only is this recording just the 3rd performance of the work in over 40 years – it would seem to be the first proper professional traversal. Again on YouTube a wobbly recording of a very flawed performance given by Gipps and her London Repertoire Orchestra barely hints at the stature of the work.

Because make no mistake this is a work of genuine stature revealing a composer working at the height of their powers. Certain Gippsian fingerprints are evident from her skilled scoring and lyrical writing for solo instruments. But there is a sweep and scale here – the 6 horns have several exciting passages – as well as the use of tuned percussion and the two harps that expands Gipps timbral palette in a rich and effective manner. At points there is almost a Baxian urgency and dynamism in her writing. Of course by the contemporary music measure of 1982 this is conservative stuff. Around this time I was part of several contemporary music groups recording a lot of ‘new’ music for the BBC – we never got sight nor sound of any score even slightly resembling this! Gipps further ties herself to the traditionalist mast by adopting a standard four movement form with a very brief intermezzo-like Andante second with a Scherzo third. The most unusual feature is a finale titled Missa brevis for Orchestra. This movement runs to just over thirteen minutes but is sub-divided [Chandos sensibly give each sections its own track] into sections of the Mass; Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Hosanna/Benedictus, Agnus Dei and Coda. The subtitle of “Except the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it” is taken from Psalm 127. Whether this is an expression of Gipps’ personal faith or a sly dig at the ‘heathens’ who ignored her labours is not clear.

From the work’s opening bars with glistening percussion and sweeping harps this is quite a different soundworld. A main Allegro vivace is soon reached although more memorable is the following Andante where a repeating chordal sequence underpins some woodwind pastoral musings which faintly reminded me of Bridge’s Enter Spring. Indeed without resorting at all to pastiche there is a sense that Gipps is invoking musical inspirations from her earlier years. This is unrepentantly backward looking almost nostalgic – but very beautiful and deeply sincere – music. The Enter Spring music occurs twice building the second time to rapturous climax with the horns unleashed in a passage Bax would have been proud of – and I suspect the BBC PO players relished here. The second movement is just 3:40 and has the feel of a pastoral interlude. The scherzo that follows is good natured and bustling and follows the traditional scherzo-trio (meno mosso)-scherzo da capo-coda format. Again Gipps deploys her orchestra to lush effect with a vibraphone adding to the languor of the trio – where woodwind solos again feature prominently as well as an extended viola(?) solo. Many of the solo lines are both extended and demanding – another choice that implies that Gipps was writing exactly how and what she wanted with little regard to the practical performing implications. Of course, no surprise that all of the BBC PO principals play these solos with great technical skill and musical empathy.

Biographical details about Gipps are limited and the list of works on the Wikipedia entry does not particularly suggested a composer of strong religious beliefs. However the closing Missa Brevis along with the marking S.D.G. [Soli Deo Gloria – Glory to God Alone] which Chandos add to the track listing without comment suggest a religious motivation. S.D.G. was added by Bach to all his sacred works so perhaps there is some acknowledgement there too?

This finale is a very effective and rather beautiful conception. The six horns intone the Kyrie and set the mood of devotion. Lewis Foreman points out that the rhythms and melodic shape of the material for each section seems to evoke or suggest the words of the Mass. This is clear enough that the thought had occurred to me having listened to the movement without having read the liner. The Symphony was dedicated; “To Sir William Walton by permission” although there is little Waltonian in the score. Perhaps the heraldic trumpet writing in the Gloria is passingly reminiscent of Walton in Henry V mode. I wonder if he ever saw the score – he died between its completion and first performance. After the almost military vigour of the Hosanna the music relaxes into a gently pastoral Agnus Dei which – perhaps unsurprisingly features one last musing solo for the Cor Anglais before a brass led warmly dignified chorale builds towards the bell-chiming Coda which feels affirmatory with brass fanfares recalling Vaughan Williams’ Sancta Civitas before a sudden hushed string passage ascends into a haze of harp swirls before fading into visionary silence. The ending happens rather quickly and for some reason I was expecting more explicitly upbeat. But actually the choice Gipps made is all the more touching for being unexpected. Much as Vaughan Williams at the end of his final symphony there is a sense of reaching out into the unknown.

The completion of this survey of the Gipps Symphonies shows these five works to be the product of an individual of real skill and ability with a musical voice which, while sharing characteristics with her colleagues and contemporaries manages to remain distinctive and original. There are still a significant number of Gipps scores – including choral – waiting to be recorded and reassessed. The hope must be that the sheer quality of the music revealed so far will encourage Chandos and these same artists to continue their exploration.

Nick Barnard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free