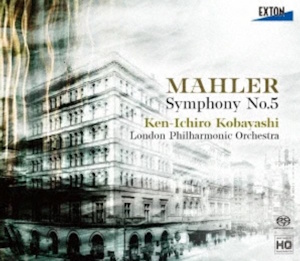

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor

London Philharmonic Orchestra/Ken’ichiro Kobayashi

rec. 2024, Abbey Road Studios, London

Exton OVCL00859 SACD [81]

I am sure if most people reading this were asked to produce a list of the finest Mahler conductors active in the world today, only a small handful would think to include Ken’ichiro Kobayashi. This would be disappointing for a musician who is so well-known and revered in his homeland of Japan that by simply mentioning his nickname, ‘Kobaken’, everyone knows who is being talked about – I could be wrong, but the only other conductor I can think of who has been afforded that same level of familiarity, is a certain ‘Lenny’. High praise indeed then.

Personally, I have come across the work of Kobayashi several times in recent years, not least in my surveys of Mahler’s First and Seventh Symphonies, where the recordings by this conductor were distinctive enough, in my opinion, to be nominated as one of the top recommendations for both works. I have yet to start my survey on the Fifth Symphony, but when I do will be referencing the excellent discography on the Mahler Foundation website as my starting point and that tells me this is the fourth recording Kobayashi has made of Mahler’s Symphony No 5, the fifth if you include a filmed version on DVD, a remarkable achievement for a conductor who has yet to complete the cycle. It gives me no pleasure then to say that his latest release is never going to feature in anyone’s shortlist of finest recordings of this work. No complaints about the sonics nor the playing of the London Philharmonic, the former glowing and expansive that frames playing of great finesse, as well as power, from the orchestra. Rather, the problem is the timings as, for a symphony that rarely takes longer than an hour and a quarter in performance, to convincingly weigh-in at over eighty-one minutes there are going to have to be some really special insights, which I am not sure are provided here.

Herbert von Karajan once said about Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, that by the time you have got to the end of it, you have forgotten how it had all begun. So in a work that opens with a grim funeral march, followed by another dark and violent movement where the clouds only part briefly to reveal the ‘promised land’, before a central bitter-sweet Ländler with snatches of waltzes forming a middle section, until the love song of the penultimate movement is then followed by a final, triumphant rondo, there are plenty of opportunities for individuality along the journey, even if not every conductor has to stretch the Adagietto to sixteen minutes, as Herman Scherchen once did in a live performance with the Philadelphia Orchestra (the radio broadcast for which is currently available on Tahra). However, with Kobayashi here, everything is just infused with a sense of world-weariness that after a while is just enervating. In a first movement that lasts some two minutes longer than the usual twelve-and-a-half, the performance is too often sluggish with climaxes that are soft-centred when they should instead rage and strike terror in the listener; it is not the awe-struck dread of observing a funeral procession ominously pass by, as Mahler once characterised this movement, but rather the detached indifference of the corpse lying in the coffin on the cortege —presumably uninterested with the proceedings. It appears that Kobayashi may have been influenced by Bernstein’s later recording of the work, which employed similarly measured tempos in this movement; however, despite both conductors being renowned for their distinctive monikers, Kobakan is not Lenny—and perhaps more significantly, the orchestra appears wholly unconvinced.

Things improve in the following movement to the extent that I found myself wondering if maybe the first movement was just a rare miscalculation on the part of the conductor, a thought which continued into the opening of the central scherzo, where the glowing Exton sound illuminated the radiant playing of the orchestra until as early as bar 136, the score indicates Etwas Ruhiger (slightly calmer). Here, with a blast from the French horns, the sparkle of the opening music gives way to something more seductive, an intimate waltz with soft, suggestive glissandi in the strings; however, Kobayashi slams on the brakes and all the good work from the previous movement fatally starts to unravel with his slow-motion tempo and the performance becomes hopelessly becalmed – from which it never recovers. Further on, the eleven minute Adagietto is played beautifully and interpreted wisely, but the performance now is simply dead in the water and so just drags, with the subsequent Rondo finale slowly sinking to the depths of ignominy, in spite of valiant efforts from the London Philharmonic’s magnificent brass section, especially at the end.

Occasionally, a leisurely interpretation of a work can result in astonishing insights to the music and textural balances – Kobayashi’s account of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony with the Czech Philharmonic is indeed an excellent example of that. However, sadly, this new release is a disappointing Mahler Five and one that should not replace any of your favourites, nor the top recommendations, which for me currently remain Bernstein with the NYPO (which I prefer to the larger than life Vienna PO remake), Klaus Tennstedt live on EMI/Warner with the London Philharmonic in 1988, Rafael Kubelík live with the Bavarian RSO (Audite, 1981), Karajan/Berlin PO (DG), Frank Shipway/Royal PO (Tring Classics), as well as the oft-overlooked James Levine and the Philadelphia Orchestra (BMG). If you must have ‘Kobakan’ in this work, then his account with the Czech Philharmonic from 1999 on Canyon is not only ten minutes faster, but ten times better than this new account.

Lee Denham

Availability: Exton