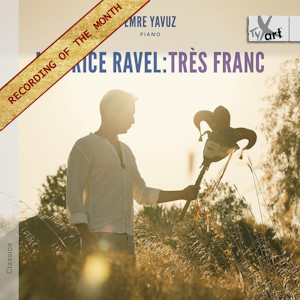

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Très Franc

Jeux d’eau (1901)

Miroirs (1905)

Sonatine (1905)

Menuet antique (1895)

Valses nobles et sentimentales (1911)

Pavane pour une infant défunte (1899)

Emre Yavuz (piano)

rec. 2024, Bösendorfer Klaviermanufaktur, Weiner Neustadt, Austria

TYXart TXA24192 [82]

In March 2021 I requested to review a disc of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Sonata No.2 on little more than a whim. The Turkish-born, Vienna-living pianist was Emre Yavuz and that was his debut disc. That recording remains one of the finest piano recitals I have had the pleasure of reviewing for Musicweb and easily made it into my “Recordings of the Year”. I must admit to having been waiting rather impatiently for the next offering from Yavuz although with the bar set so high by the initial release the concern would always be that the previous technical standard and levels of musical insight would be challenging to match. Rather wonderfully I am delighted to report that this very different collection is every bit as good.

Yavuz contributes the detailed and personable liner note that combines useful information about Ravel and the music but also his own approach to the music. Interestingly, Yavuz reveals that he had decided upon a Ravel recital as his next project in the months before recording the Rachmaninoff. Quite why the wait has been four years is not clear although it is apparent that Yavuz needs to be completely consumed and in the thrall of a composer before he feels he can do the music full justice. Of course the delay means that this disc is released almost exactly on the 150th anniversary of Ravel’s birth on March 3rd 1875 and it will be just one of a flood of recordings celebrating this sesquicentennial. And all of those will in turn be adding to a catalogue groaning with classic recordings by all the great and the good from the last century of recorded sound. Many of those recordings claim to offer the “complete” works for piano. As is often the case quite what constitutes complete is open to debate with different collections offering different solutions. Yavuz neatly avoids such contention by presenting a single disc – albeit exceptionally generous – selection of the core solo keyboard works. The main works that are omitted are Gaspard de la Nuit and Le Tombeau de Couperin. But as he did with his Rachmaninov programme, Yazuv has subtly crafted a programme which seems to have a musical arc and satisfying shape that makes the whole even more rewarding as a listening experience.

In part this has been aided by an absolutely top drawer recording and production with the Bösendorfer 280VC – Vienna Concert caught magnificently with superb clarity in the upper register and warmly resonant – but not tubby – rich bass. The recording is a 24 bit/96 kHz recording but not in an SACD format but to my ear this is demonstration class. All of which allows Yavuz to demonstrate his immaculate musicianship. Poise, clarity and balance are three words that recur in my listening notes. Clearly those are qualities that are necessary and present in many recordings of this music. But part of my particular pleasure here is that they are only part of a wide-ranging expressive palette that Yavuz deploys. This is not simply the ‘Swiss Clockmaker’ style of Ravel performance. I found Yavuz’s handling of rubato and expressive freedom to be entirely convincing. He did the same in his Rachmaninoff recital where nothing was extreme or disfiguring while remaining quite individual but there, as here, I found it compelling and illuminating. The other brilliantly achieved aspect of the playing here is the internal balancing of the various musical lines. The result is a clear sense of the layers within the writing – the chiming bells of La vallée des cloches have rarely created such an aural illusion of depth and space as here.

Given the complexity of the writing it is no surprise that many of these works were latterly orchestrated by the composer or others. I have to say it is the orchestral versions I tend to listen to more frequently than these keyboard originals. A measure of the success here is that more often than not Yavuz convinces me that these versions are even more effective. This is in part due to the use of rubato mentioned above. A solo player can apply tiny little expressive nudges that an eighty piece orchestra cannot. Of course the trade-off is the opulence and scale an orchestra in full-flood can offer but the big climaxes of works such as Alborada del gracioso as performed here are as thrilling as ever.

The recital opens with the seminal Jeux d’eau. As Yavuz mentions in his liner this work from 1901 is often credited with being the first work of piano Impressionism. There is no need to become bogged down in that debate – what is not open to question is just what a remarkable and indeed important piece it is. As Yavuz writes; “It would not be an exaggeration to say that with Jeux d’eau Ravel became Ravel”. Indeed the compositional balance of form, harmony and fluid rhythm is the very essence of Ravel’s finest music. Additionally Yavuz finds a capricious playfulness here – and indeed throughout the programme – that to my ear seems to be a key part of Ravel’s compositional personality.

Placing the full set of the five Miroirs next, written just four or so years later, is intelligent and effective. The progression not just in compositional technique but refinement of the elusive aesthetic behind the notes is marked and striking. One hundred and twenty years after they were written these still sound remarkably modern. Apart from the sly good humour and energy of Alborada del gracioso these works touch on polytonality, polyrhythms, birdsong, a kind of proto-minimalism amongst other devices that are employed and exploited to this day. Another of the aspects of Yavuz’s playing that strikes me as fully effective and impressive is that he adapts his playing technique and style from piece to piece and often paragraph to paragraph within a piece. I cannot claim to have a great knowledge of performances of this repertoire but I do feel there are occasions when playing of great technical address is compromised by a stylistic limitation that relies too heavily on precision allied to emotional aloofness. Yavuz brings an element of expressive impetuosity to his interpretations that to my ear seems both apt and engaging.

The direct contrast in terms of both music and execution with the following Sonatine is once again striking and effective. This is all the more remarkable given that this work was written at exactly the same time as the Miroirs. Yavuz neatly sums the work up as follows; “If we were to place all of Maurice Ravel’s piano works on a spectrum with modernist at one end and neoclassical at the other, Le tombeau de Couperin would sit at the classical end, Miroirs at the most modernist, and Sonatine would lie perfectly at its centre”. Yavuz’s performance reflects this with a performance of perfect control and beautifully graduated dynamics and expression. Whilst this work does have a neo-classical clarity again I find Yuvaz’s judicious and carefully graded use of rubato and rhythmic freedom imbues the work with an air of heady impetuosity that is completely natural and wholly convincing.

The Menuet antique was written nearly a decade earlier thereby pre-dating the ‘breakthrough’ musical vocabulary of Jeux d’eau. Again, the placement of the work in the context of this recital is illuminating with pre-echoes of the Sonatine and impressionistic Miroirs jostling with gestures and phrases showing an allegiance to older French contemporaries – again this receives a sympathetic and insightful performance. Ravel’s fascination for waltz form and the music of Schubert came together in his 1911 work Valses nobles et sentimentales. In the liner Yavuz makes the valuable point that around the time of its composition there was active debate, especially in France, regarding the enduring legacy of Wagner and his musical philosophy. With works such as the Valses nobles, Ravel sought to celebrate pure music to be enjoyed for enjoyment’s sake – of which the Viennese waltz could be seen as the ultimate hedonistic expression. The result is a work of maximum grace and elegance with textures of light and airy beauty. Given its Viennese/Schubertian inspiration perhaps it is slightly paradoxical that the first movement is given the direction “très franc” which in turn – very aptly – is the title of this collection. I must admit, this is not usually one of my favourite Ravel works in any guise – keyboard or orchestral – but there is something Yavuz’s playing that I found completely absorbing. Does he find an extra degree of lilt to his waltz rhythms or am I just imaging that given his Viennese roots? Again, the collective quality of this recording is superb and the result is the finest performance of this work I have heard.

Listed as a ‘bonus track’, the Pavane pour une infant défunte of 1899 completes the programme with a performance of disarming simplicity and charm. Given the qualities exhibited throughout this disc, this feels like an apt and appropriate conclusion to this genuinely impressive and insightful recital. 2025 is bound to see a deluge of collections and recital featuring Ravel’s music all jostling for the listener’s attention – this one puts down an early marker of excellence that will be hard to surpass. The hope must be that Emre Yavuz will not wait quite so long until his next recording venture. An unqualified triumph.

Nick Barnard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free