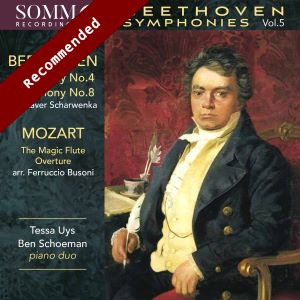

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Symphony No 4 in B-flat major, Op 60 (1806, arr. piano four-hands by Franz Xaver Scharwenka)

Symphony No 8 in F major, Op 93 (1812, arr. piano four-hands by Franz Xaver Scharwenka)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Overture BV B 93 – The Magic Flute K.620 (1791, transcr. for two pianos by Ferruccio Busoni)

Tessa Uys and Ben Schoeman (piano duo)

rec. 2023, The Menuhin Hall, Stoke d’Abernon, Surrey, UK

Beethoven Symphonies Vol. 5

First recordings (Beethoven)

SOMM Recordings SOMMCD0687 [67]

At first sight, the novelty of Beethoven symphonies being played by piano four-hands is a quaint notion from a 21st century perspective – and, it seemed to me, not that interesting to review. Until, of course, one considers the importance of piano transcriptions and arrangements in the context of 19th century Europe before the first recording technologies of the new century appeared. For a sophisticated, reasonably well-to-do family in a location remote from symphony orchestras in the major capitals, hearing the latest orchestral works in the form of a piano arrangements – in their living room, with family and friends – would have been a major and most welcome social and musical event. Granted, a resident or touring piano virtuoso or two would also have been needed too – these are not your average parlour pieces. A novelty born out of necessity, then, perhaps more interesting than I initially thought.

The piano duettists in this recording are almost contemporaneous South African compatriots of mine. I’ve heard them both performing in London and I well remember hearing Tessa Uys playing with the Cape Town Philharmonic Orchestra in the City Hall – I can’t recall if I heard Ben Schoeman playing in Cape Town. So, with a touch of nostalgia, I was finally enticed to do a review of this disc. I’m glad I did – it turned out to be very rewarding.

Franz Xaver Scharwenka (1850-1924) was a noted German composer, pianist, and pedagogue of Polish and Bohemian descent; although working in the milieu of early Modernism, his works were firmly rooted in the 19th-century Romantic tradition. His symphony and four piano concertos are probably his best remembered works. In the closing decade of the 19th-century he created ingenious piano duo arrangements of Beethoven’s symphonies that reflect his deep understanding of both Beethoven’s orchestral writing and the capabilities of the piano. There is an unbroken link back to the composer himself, for Scharwenka was a pupil of Franz Kullak, who studied under Beethoven’s pupil Carl Czerny. These arrangements are part of the 19th-century tradition of adapting orchestral works for smaller forces, making them accessible for home performance or study.

Scharwenka’s arrangements for four-hands on a single piano stand out for their technical finesse and musical insight, the two pianists more faithfully capturing the dynamic contrasts, contrapuntal lines, and dense harmonic layers of Beethoven’s symphonies than a solo pianist could. He carefully adapted the orchestral parts to the piano duo, balancing the technical limitations of the keyboard with the need to convey Beethoven’s grandeur and complexity. The arrangements are demanding for both pianists, incorporating virtuosic passages that maintain the intensity of the symphonies, and require advanced technical skill and careful ensemble playing. Scharwenka’s transcriptions have been praised for their craftsmanship and artistic quality. While little known today, they are significant contributions to the piano duo repertoire and follow the tradition of composers like Franz Liszt (1811-1886) who transcribed all Beethoven’s symphonies for solo piano. The cruelly demanding Liszt solo piano arrangements were completed between 1840 and 1865 and are by far the best known of the Beethoven symphony arrangements and have been widely recorded. Liszt also made a two piano four-hand transcription of Symphony No 9 in 1853.

Austrian composer/pianists, Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837) and Carl Czerny (1791-1857) were younger near contemporaries of Beethoven and also made piano arrangements of his symphonies. Hummel made chamber arrangements of all the symphonies for flute, violin, cello and piano (c.1825-1835) as well as solo piano transcriptions of Symphonies Nos 2, 3 4 and 5 (c.1827-1832). Czerny made transcriptions for piano four-hands of all nine symphonies between 1814 and 1836.

Other prolific arrangers of Beethoven’s symphonies were, amongst many other virtuoso pianists, German pianists Wilhelm Meves (1808-1871) and Theodor Kirchner (1823-1903) who arranged all nine symphonies in the 1880s; Meves for piano four-hands and Kirchner for two piano eight-hands. Austrian pianist Ernst Pauer (1826-1905) made piano solo arrangements just prior to 1900 of all the symphonies, except for Nos 5 and 6. None of these has been recorded as far as I can find out.

The earlier arrangements by Hummel and Czerny would have been made for the more delicate and intimately-toned, wooden-framed piano. These instruments were limited by the tensile strength of wood and could only support lower string tensions, resulting in softer and less resonant tones. They couldn’t withstand the tension created by higher-pitched strings or the thicker, longer strings needed for greater volume and tonal range. They would have struggled to reproduce the complexity and power required by Beethoven symphony arrangements.

The invention of the single piece cast-iron frame by the American piano maker Alpheus Babcock in 1825 marked a major milestone in the history of piano design and construction and by the 1840s had become the standard in modern pianos. The iron frame allowed pianos to use more strings at higher tension, significantly enhancing their tonal power, sustain, and stability. This offered a broader dynamic and tonal range and a richer, more powerful sound. It transformed the piano into a robust and versatile powerhouse capable of meeting the demands of modern music. In short, just the instrument needed to convey the grandeur of Beethoven symphony arrangements by a solo piano, piano four-hands, two piano four-hands or two piano eight-hands.

The recording being reviewed is Volume 5 of the six volume series released by SOMM Recordings of the Scharwenka transcriptions. Volume 1 covered Symphony No 3 (review) and Volume 2 covered Symphony No 5 (review) – both were enthusiastically recommended by Jonathan Welsh for MWI. None of Volume 3 (Symphonies Nos 2 and 7), Volume 4 (Symphonies Nos 1 and 6) or Volume 6 (Symphony No 9) have been reviewed here. The series has garnered critical acclaim underscoring the high regard in which Scharwenka’s transcriptions, and the performances by Tessa Uys and Ben Schoeman are held. Their technical proficiency, interpretative insight and the successful revival of these noteworthy arrangements have been a revelation. All are first recordings, except No 7, which was recorded by Duo Trenkner/Speidel on MDG Gold in 2013; it has also not been reviewed by MWI and seems no longer to be available.

Tessa Uys was born in Cape Town and was taught by her mother, Helga Bassel, a successful German Jewish concert pianist who moved to South Africa when the Nazis came to power. Straight out of school, Uys continued her training at the Royal Academy of Music in London. She is now based in London where she has an established career as a teacher and a concert and broadcasting artist in the UK and Europe.

Ben Schoeman trained at the University of Pretoria, at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London and at the University of London. In 2016, he obtained a doctorate in music from University of London and the Guildhall School of Music & Drama with a thesis on the piano works of the South African composer, the late Stefans Grové. He performs regularly in the UK, Europe, South Africa and the USA. Dr Schoeman also teaches piano and musicology at the University of Pretoria.

Uys and Schoeman have performed regularly as a duo partnership since 2010. In 2018, they embarked on their journey with the nine Scharwenka piano duo arrangements of the Beethoven symphonies, beginning with a live performance of the Ninth at St Michael’s Church, Highgate in London which was televised widely and was very well-received critically (you can hear it on YouTube). In 2021 the duo built on that acclaim and started recording the Scharwenka arrangements of all nine symphonies for SOMM Recordings.

The pairing of Symphonies No 4 and No 8 on this disc is apt. Both are mostly sunny, light-hearted and upbeat works, showing a determination by Beethoven to create in the face of the despair he felt at his growing deafness. Standing in the shadow of giants, neither has garnered the public acclaim enjoyed by their siblings. They were admired by later composers like Schumann, Mendelssohn and Berlioz. Indeed, Schumann referred to the Fourth as “a slender Greek maiden between two Norse giants”. Both look back to Mozart and Haydn; the Fourth, lyrical, lightly-scored, standing on the cusp between the Classical and the Romantic and the Eighth looking back nostalgically to the Classical symphonic form, full of vivacity, wit and humour, adding playful rhythmic complexity to Romantic melody and harmony.

Schoeman plays primo in Symphony No 4, which opens with delicate playing in the brooding and suspense-filled Adagio string introduction to the Adagio-Allegro Vivace first movement, with the horns and woodwinds slowly making their introspective entrance. The piano playing here is atmospheric and mysterious, expertly creating a sense of unresolved suspense. The bouncy, syncopated first theme is played with rhythmic energy and gusto. This is not reticent playing – Schoeman and Uys establish early on that their approach is big-boned, which really suits Scharwenka’s faithful arrangement. The lyrical second theme on strings cantabile with woodwind accompaniment is beautifully realised with song-like playing by the duo. The recapitulation and playful coda are played with joy and great energy bringing the movement to a triumphant close.

The Adagio second movement opens with the serene, yearning melody by the violins and woodwinds, underpinned by the gently rocking ostinato accompaniment on the lower strings. The movement travels into darker minor key regions of emotional tension before returning to the reflective “heartbeat” melody of the opening. This movement is played attentively and with profound serenity by the duo who bring it to an exquisite close. Very impressive.

The third movement Scherzo-Trio is whimsical – full of wit, rhythmic contrasts and sudden changes in dynamics. The Scherzo opens with a vigorous, “hopping” theme that is full of energetic, syncopated rhythms. The Trio is gentler and bucolic in nature – a gentle flowing melody in the strings and woodwind punctuated by horn calls before returning to the frenetic Scherzo theme. The duo play this movement very fast, but with precise, crisp articulation. Great fun.

The final movement, marked Allegro ma non troppo, opens with a skittering, exuberant theme played by the strings which gallops along with irresistible momentum. After a playful and joyous Rondo, the coda is a whirlwind of energy which builds in intensity and speed. This exhilarating movement, bursting with joy and playfulness, comes to triumphant and uplifting conclusion. Once again the duo play this movement quicker than most orchestral versions, but with the facility and cohesiveness of a twenty-fingered soloist.

What a charming symphony No 4 is and how well Scharwenka has caught Beethoven at his most genial. Schoeman and Uys have brought this faithful arrangement to life in a performance to be greatly admired.

Symphony No 8 is compact and playful, often affectionately called “My Little Symphony” by the composer. This time Uys plays primo. The Allegro vivace first movement erupts immediately with a buoyant opening theme in the strings and woodwinds which the duo play with vigour and precise articulation. The graceful second theme does not slow the headlong rush and after some mischievously inventive development of the themes, the coda brings the joyous momentum to rest.

The second movement Allegretto scherzando is one of Beethoven’s shortest symphonic movements and opens with a mechanical “tick-tock” rhythm in the woodwinds. The main body of the scherzo features a dance-like theme with unexpected accents and rhythmic twists. The trio introduces a reflective, pastoral melody before the scherzo returns with the persistent “tick-tock” motif and the brief coda brings things to an abrupt conclusion. The duo play this movement at a leisurely pace making the most of the rhythmic twists and turns so well captured by Scharwenka.

Rather than his usual scherzo, Beethoven returns to the more Classical minuet form in the Tempo di Minuetto third movement. Again this is a very short movement. The minuet section is a genteel and stately dance and my only minor quibble with this performance is that Uys and Schoeman play the minuet, while still beautifully phrased, slightly too fast for my liking – its elegance is somewhat diminished. The pastoral trio section, featuring the beautiful horn duo with woodwind accompaniment which creates a distinctive hunting call character, is well-wrought by Scharwenka and finely played. A short coda brings a gentle finality to the movement.

The Allegro vivace finale is a tour de force of orchestral writing and opens with an explosion of energy and rhythmic propulsion. Against all odds, Scharwenka’s arrangement manages to recreate the excitement and drama of the sudden dynamic contrasts and unexpected harmonic shifts of the orchestral original. The duo produce some of their most robust and thrilling playing in this movement. The jubilant and exhilarating coda, brings the symphony to a triumphant and uplifting close.

This symphony is lively, inventive, and full of surprises. Its brisk pace and dynamic shifts evoke both exhilaration and a sense of wry humour. Scharwenka’s arrangement is wholly successful in reproducing this. Uys and Schoeman play as though their lives depend on it – bravo!The disc closes with Ferrucio Busoni’s 1923 transcription of Mozart’s The Magic Flute overture for two pianos four-hands. The transcription is part of his broader endeavour to reinterpret and adapt classical works for the piano, a practice he also applied extensively to Johann Sebastian Bach’s compositions. His approach to transcription often involved a balance between preserving the integrity of the original piece and infusing it with his own pianistic insights. The piece has been recorded before by Emil Gilels & Yakov Zak (review), Daniell Revenaugh and Lawrence Leighton Smith on EMI (2007) and the Duo Grau/Schumacher (review). It is an enjoyable transcription and receives an exciting performance by Uys and Schoeman.

.I enjoyed this disc immensely, both as first recordings of the Scharwenka piano duo arrangements of these two lovely symphonies and as works which can stand on their own merits as fine chamber pieces. The playing of Uys and Schoeman is of the highest standard and they present these works in their glowing light. The sound quality is outstanding in a well-known, acoustically sympathetic venue.

The liner notes by English composer, writer and broadcaster, Robert Matthew-Walker, are informative and well-written, but unfortunately pages 3, 4, 9 and 10 were missing from my copy of the CD liner notes. However, they were easily found on SOMM Recordings’ website.

These are fine first recordings which can be confidently recommended to admirers of Beethoven’s symphonies – you’ll properly hear things in these transparent piano arrangements you haven’t heard before. I look forward to reviewing Volumes 3, 4 and 6 soon.

Terry McSweeney

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free