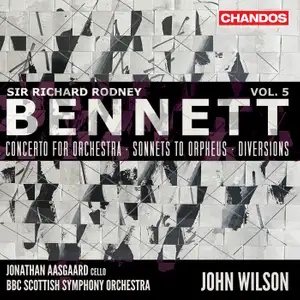

Sir Richard Rodney Bennett (1936-2012)

Concerto for Orchestra (1973)

Sonnets to Orpheus (1978–79)

Diversions (1989)

Jonathan Aasgaard (cello)

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/John Wilson

rec. 2023, City Halls, Glasgow, Scotland

Chandos CHSA5266 SACD [72]

In many ways this is an unnecessary review. Enthusiasts for the music of Richard Rodney Bennett or collectors already convinced by the superb quality of Volumes 1-4 in this series will not require any prompting to acquire this latest addition. The reality is that this developing survey is unlikely to ever be challenged, let alone surpassed.

Conductor John Wilson had a close personal and professional bond with the composer and his musical strengths very much chime with the requirements and characteristics of these often demanding and complex scores. Likewise in the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra Wilson has found an ensemble completely at ease with this idiom producing performances that sound wholly engaged and superbly skilled. The final consideration is the top-drawer excellence of Chandos’ SACD engineering and production. This showcases just how good SACD can be; it is not a question of sonic impact or ridiculous dynamic range. Rather there is an airy precision that serves the music so well. Bennett was a master orchestrator with flecks of percussion or detailed inner instrumental detail requiring not just very precise playing but a super-accurate representation of that playing. This it receives here and throughout this series of recordings.

All of which allows the listener to focus their attention on the music itself – often far from ‘easy’ to grasp – certain in the knowledge that it is being presented in the best possible manner. As before Wilson/Chandos have put together a generous and diverse selection of works that reflect different aspects of Bennett’s output and the strongly contrasting scale and musical goals. This is of course an accurate reflection of his remarkable musical range as both performer and composer. Richard Bratby’s liner note is excellent; both entertaining and informative. Bratby charts Bennett’s move from the European avant-garde to a style and musical voice that “people will need, and which preferably, will sound beautiful…”. Bratby also charts a slightly uncomfortable professional relationship with Benjamin Britten (neither the first or last musician to have such) while feeling William Walton was “more congenial company”. Interestingly although the Concerto for Orchestra that opens this disc is in part based on a Britten theme, there are passages in the later Sonnets for Orpheus that share a Waltonian spiky rhythmic and harmonic character.

The Concerto for Orchestra dates from 1973 when Bennett’s ‘serious’ music [his wonderful film score for Murder on the Orient Express was only one year in the future] was still quite terse. But of course, when a master orchestrator such as Bennett composes a work explicitly as a showcase for a modern symphony orchestra you can expect it to be full of effective if challenging writing. The work is in three roughly equal length movements although the third sub-divides into a theme, eight variations and a finale. The work premiered in Denver in 1974 conducted by Brian Priestman. From the very opening bars this is Bennett at his most uncompromising. The writing is brilliant, even flamboyant as befits a display work such as this, but it is also quite severe. The BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra responds with playing of easy virtuosity and when the numerous passages occur that allow section principals to shine they are taken with great skill. “Tension” is a word quoted from Bennett’s own description of the central combine slow movement/scherzo and it is a characteristic that could be applied to the whole work. Not that it lacks passages of stillness or reflection but even here there is a sense of veiled anxiety or implicit restlessness. What is striking – and this has been true of all the works presented as this series develops – is that Bennett’s musical voice is quite different his contemporaries in the British musical scene. But perhaps in this work he tries just a little too hard to be seriously distinctive. I find myself admiring the work more than liking it and perhaps Bennett’s growing awareness of the importance of allowing the listener to have an emotional connection with his music prompted the shift in style that Bratby alludes to above. Nothing on this Chandos release suggests that this is a premiere recording but checking the usual discogs sites (there is no site apparently dedicated to Bennett) lists no other version(s).

In Bratby’s words by 1979; “Bennett was at something of a crisis [having] drifted apart from the avant-garde establishment.” Alongside a professional upheaval, in late 1978 Bennett split from his long-term partner and decided to move permanently to the USA. At the same time as this significant upheaval Bennett started composing his Sonnets to Orpheus – a cello concerto in all but name. Bratby considers this work; “one of the great English cello concertos” and in a performance as committed, convincing and powerful as this it is hard not to agree. The only real surprise is that it has had to wait 45 years for a first recording. If the Concerto for Orchestra is a brilliant but emotionally distanced orchestral study, this work takes that same brilliance of technique but fuses it with an emotional weight and engagement that makes it a deeply engaging listen. Bennett dedicated the work to his former partner Dan Klein which Bennett’s biographers have interpreted as both an apology and a justification for his decision to pursue his musical imperatives regardless of personal cost. The title is derived from a group of poems so named by Rainer Maria Rilke which each of the five movements headed by a quotation from one of the poems. The quite excellent cellist is Jonathan Aasgaard who apart from his solo playing is principal cellist of both the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and Wilson’s own revived Sinfonia of London. The Sinfonia connection is furthered by that orchestra’s leader John Mills guest-leading the BBC SSO on this disc.

The Rilke quotes are by no means vital to the understanding or enjoyment of the work. I imagine they were points of inspiration or initial departure for Bennett but the abiding impression is of powerful work that exploits the lyrical and virtuosic potential of the instrument right down to the judicious use of cadenza passages in a fairly ‘traditional’ concertante manner. Chandos have created an excellent orchestra/soloist balance with the latter clearly present throughout but without seemingly overly inflated on the soundstage. This is the most substantial work on the disc with the five movements totalling 32 minutes but the feel is of a more traditional three movement work since the second and third movements run together as do the fourth and fifth. All three of the main sections end with the soloist in the highest register fading to silence. Perhaps after the arms-length objectivity of the Concerto for Orchestra this work emerges as almost too personal, too intimate and confessional but my strong impression is that this is as genuinely a great concerto as Bratby suggests even if it is not one that surrenders its secrets easily. Although the work has waited several decades for any kind of acknowledgement let alone appreciation this quite magnificent performance will surely help redress that balance. I must admit I have enjoyed all of the concertante works that have appeared scattered across the previous releases in this series. They have all been wonderfully played and have revealed very attractive scores. But this Sonnets to Orpheus strikes me as the finest yet with Bennett drawing on deep wells of personal emotion and engagement to place alongside his usual compositional flair and skill..

Those latter talents are very much on display in the Diversions for Chamber Orchestra that closes this disc. This exuberant and thoroughly entertaining work has been recorded before – 30 years ago on Koch by James DePriest and the slightly improbable Orchestre Philharmonique De Monte-Carlo. At the time that was a valuable disc simply for being devoted to Bennett’s music. To this day it contains the only commercial recording of the Violin Concerto. The older version of Diversions is perfectly good but it is superseded in every respect by this new version which is better recorded, more characterful, better played and just more convincing – Wilson is nearly a full minute quicker than De Priest to good effect. The work was a commission by a group of London schools which was premiered by an orchestra drawn from those schools at London’s Royal Festival Hall in 1990. Although by no means easy, Bennett’s set of six variations on Scottish folksongs is a delight from first to last. Perhaps this embodies his previously stated wish to be actively enjoyed by his audience (and players). Bennett finds a sly wit and Portsmouth-Pointian sparkle and playful energy in these variations that he seemingly consciously avoided in the finale of the Concerto for Orchestra. The scoring shows how skilled Bennett could be with just standard double wind and a pair of trumpets alongside usual strings, timps, 2 percussion and a piano. Certainly for Chamber Orchestras or ensembles with numbers of players constrained by budgets this is a work that would be an attractive part of any concert programme.

The consistent quality of this series has been a notable feature. But I have to say this new release might just be one of my favourites – in part because the cello work is so impressive but also because the programme provides such a good overview of Bennett’s work and how it transformed between 1973 and 1989. Looking at various lists of works written by Bennett it would seem that even after five well-filled volumes, there is a lot of substantial music yet to be explored. The hope must be that this unmatched and definitive series will continue for several more volumes.

Nick Barnard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Previous reviews: Philip Harrison (February 2025) ~ Stephen Barber (February 2025)