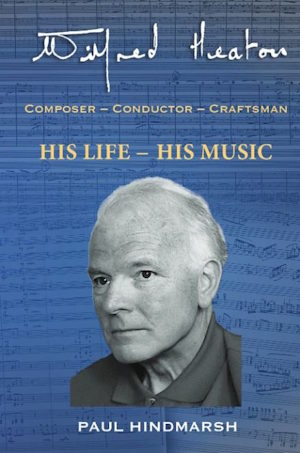

Wilfred Heaton: His Life – His Music

by Paul Hindmarsh

Hardback, 464 pages

Published 2025

ISBN: 978 1 03690 132 5

PHM Publishing & Production

“Why should the Devil have all the best tunes?” This is often attributed to the legendary founder of the Salvation Army, William Booth, but it may have been the Reformer Martin Luther, Anglican cleric George Whitefield, or the English evangelist and hymnist Rowland Hill. To be sure, the Salvation Army did get good tunes, but at some artistic cost.

Wilfred Heaton (1918-2000), born in Sheffield, England, was a distinguished composer, conductor and teacher, renowned for his contributions to brass-band and orchestral music. His musical journey began early, nurtured by his Salvation Army family. He started piano lessons at age eight, and soon began writing his own music. His career was marked by technical brilliance and innovative compositions. He gained an LRAM in piano at nineteen. He was employed in a brass instrument manufacturing and repair business while devising songs and band pieces. His works often reflected his strong religious background and philosophical interests. Much of the dynamic of Heaton’s life revolves round the tensions between his Salvation Army background, the effect of the eccentric religionist Rudolf Steiner, and his increasing attraction towards (limited) modernism. In 1971, he briefly replaced John R Carr as bandmaster of the Black Dyke Band.

Heaton’s success extended beyond brass bands to orchestral, vocal and chamber music. His music, celebrated for its complexity and sophistication, places him firmly in the European classical mainstream.

Sadly, there had been little previous study on Heaton’s life and achievement. Prior to this present volume, information had to be gleaned from a few articles in the musical press, such as Paul Hindmarsh’s Wilfred Heaton: An Appreciation (The British Bandsman, 2000), Ronald Holz’s Wilfred Heaton and The Salvation Army Reconsidered (The British Bandsman, 2004), and Howard Snell’s Wilfred Heaton (Brass Band World, 1992 and 2004). There is a reliable source of information: the liner notes Hindmarsh devised for The Wilfred Heaton Collection. I understand that there was also Philip Harper’s dissertation Music of Wilfred Heaton, University of Bristol, 1994. The Wilfred Heaton Trust website is a useful source. This book, then, is the most detailed examination of Heaton’s life and especially his music. No other composer working in the brass-band world has received this amount of research.

Paul Hindmarsh, a distinguished music producer, journalist and author, focusses on British music and brass bands. He has produced recordings for over thirty years. He is known for the essential catalogue of Frank Bridge’s music and the legacy of Wilfred Heaton. Hindmarsh also established the BBC (now RNCM) Brass Band Festival. He has received several Sony Award nominations for his radio programmes, and international prizes for his industry as a producer and curator of band music.

This new book introduces the reader to the world of Wilfred Heaton. Structurally, the volume divides into two main parts: biography and studies of selected compositions. These are complemented by a Catalogue Raisonné, a foreword by Edward Gregson, and by a preface by Bryan Stobart of the William Heaton Trust. The book concludes with a select bibliography and indices of the music and general topics.

Interestingly, Paul Hindmarsh says that the two-fold division was not his first choice. Normally, he would have used as his “preferred methodology in illuminating life and work was to connect musical commentary to inspiration, composition and reception”. But shortly before his death, Heaton told the author that he wished to keep his life and music separate. On progressing his studies, Hindmarsh realised that Heaton was right: the two facets were indeed uncoordinated.

The first part of the book, …On the Road, is the biographical section. It includes recollections of family, friends, bandsmen and colleagues, information from correspondence and archive documents, and a running text. For example, a long recollection which deals with Heaton’s wartime service is quoted by Dr Ken Tout, former Lance Corporal in the army and friend.

The second part, …Work in progress…, is a masterclass in description and analysis. Hindmarsh explains: “My commentaries adopt a narrative methodology. When appropriate I offer personal interpretations of descriptive or programmatic content but always based on musical evidence. To that end I employ some technical terms that require explanation, particularly regarding matters of tonality and key.” There are twelve “Studies”, each looking at a series of Heaton’s output in largely chronological order. This comprises Juvenilia, Apprentice pieces with brass, and Transformations. Many compositions have been examined, with plenty of musical examples and formal overviews, with the single aim of making Heaton’s oeuvre better known.

As with all good preachers, Paul Hindmarsh resolves Heaton’s composing activity into three main phases. The early period runs from his first listed work, The Army’s Marching Song, written when he was twelve, to music concluded in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War. It includes much specifically devised for the Salvation Army. The middle period is when Heaton adopted a “self-styled search for a more contemporary yet ‘comfortable’ language”. The finest piece from this period is Celestial Prospect (c.1950, rev.1986) and sketches for his well-known Contest Music (1973). The final phase was a time of consolidation, “repurposing and revising” older scores from the 1940s and 1950s. Yet, there was a final flowering with his magnificent Variations, which were left unfinished at the time of his death. Howard Snell completed the score.

When I talked with Hindmarsh, I discovered that all Salvation Army published band music must include hymn tunes or Christian references that are familiar to their members. Composers and bands are encouraged to produce music that reflects the spiritual work they support. The whole point is “soul saving”, which involved an uncomplicated approach to composition in which melody dominated. In the band pieces, the message contained in the text associated with the ‘borrowed’ tune was as important as the tune itself. Jazz, big band and extended tonality were anathema. Another negative effect on composers was that they must deny their own musical personality. The editorial board declined many of Heaton’s efforts, even if he showed great skill and invention.

For years, this stylistic conservatism hobbled musical progress. This caused a sizeable number of excellent brass-band composers to leave the movement. Although this aesthetic censorship is less of a problem today, all new writing is still vetted for its suitability for publishing and performing in the Salvation Army setting. What is wanted is Christian Gebrauchsmusik. Many of Heaton’s brass-band pieces have religious titles, simply because he was creating music that he hoped would be played by the Salvation Army. Hindmarsh told me: “the majority […] include some kind of hymn reference – he liked to keep them simple and then play all kinds of compositional games, which proved too ‘progressive’ for the Salvation Army in the 1940s and early 1950s.” Interestingly, selected works I listened to whilst preparing this review had religious titles but definitely employed secular trimmings.

Into this chronology one must fit Heaton’s reaction to Rudolf Steiner. It is important to note that Steiner did not see his spirituality as a religion or denomination but as a philosophical system. As Heaton recalled: “All compositional ambitions were brought to a halt through my contact with Steiner’s Anthroposophical Movement. Involvement in this seemed to dry me up. I lost the impulse to compose. Such an activity seemed unimportant compared with the spiritual impulses offered by Steiner.” How sad.

One must not forget that Heaton penned several non-brass band works of a secular nature. These included a Suite for orchestra (1950), a Rhapsody for oboe and string orchestra (1952), Three Pieces for Piano (1954), a major Piano Sonata (1950s) and a Little Suite for recorder and piano (1955). Hindmarsh gives each of them a detailed study.

A satisfactory illustration of the process of ‘transforming’ older music is the Piano Sonata. The genesis was a brass Scherzo written in 1937. It then re-appeared in 1950 as Heaton’s first orchestral work, the Suite. It was reinvented around the same time as the Sonata, before appearing as the Partita for brass band in 1984. Study VII gives a detailed account of this process. I have not heard the Sonata, but Hindmarsh says that it is the most “radical of the three iterations in language and texture”. Furthermore, the “result is an experimental opus […] complex and formidably challenging to play”. Certainly, looking at the musical examples in the book would suggest that it was as advanced as much that was being produced in Britain at that time.

I understand that later in 2025 Divine Art will be issuing a disc including this Sonata, along with songs and other piano music. The pianist will be Murray McLachlan.

Take another sample. In Study X ‘Contest Music’s Hidden Tunes’, Hindmarsh explores its origin which dated back to the 1950s and Heaton’s association with Mátyás Sieber. It began as a series of exercises in which he developed “experiments in alternative approaches to thematic development”. In 1973, Heaton began to synthesise these ‘sketches’. Hindmarsh notes there are three movements, with the first “personalising classic sonata form, [and] deploying thematic fragments to create a compact, quasi-palindromic design”. The Adagio derives from an old student exercise that “rhapsodises” rather than traditionally “develops”. And the finale, which “purports to be a rondo”, is bright and has a “muscular big-band aura”. Contest Music was designed to do just that: be used at brass-band competitions. It was rejected.

Hindmarsh then examines each movement for a series of hidden allusions to other folk’s music. He discovers nods to Hindemith, the folksong Widdicombe Fair, and Handel’s hymn tune Gopsal (Rejoice! The Lord is King). Referring again to the Adagio, it is suggested that the rhapsodic nature of the music may owe something to Swiss-born German artist Paul Klee’s contention that “Drawing is like taking a line for a walk […] moving freely without a goal”. Heaton takes his own tune for a stroll, “moving against an elusive harmonic background with the support of beautifully voiced countersubjects”. Finally, the Vivo was dedicated to Stan Kenton, the American band leader. The various thematic transformations that make up this movement’s material are explored.

Sadly, the work was not used in 1973: the authorities decided it was too “challenging” in style and duration. The late Elgar Howarth considered it a masterpiece when he gave the first concert performance in 1976. Fortunately, it became popular as a concert piece, and was eventually used in a contest in October 1982. The winner was the Cory Band.

The Catalogue Raisonné is detailed. It provides the usual information: date of composition, publication, and premiere performance if known. Each entry has been allocated a “WH” number. Within each genre, works are presented alphabetically. Details of the ‘First Recording’ are given. It is interesting to note that virtually all the brass-band music has at least one recording. This is not the case with other categories, such as the orchestral repertoire.

The bibliography is only a page long, which sadly reflects the lack of scholarly interest in Heaton up to the present. A comprehensive general index is especially helpful in locating detailed information about Wilfred Heaton’s life and times. The convenient Index of Works includes notable references to original compositions, revisions, alternative versions and arrangements by others.

PHM Publishing & Productions is Paul Hindmarsh’s self-publishing company. He typeset the text, figures and illustrations, and laid it out for the printers. This is a most sophisticated and tasteful book. It is sturdy, with a font perfect for the eyes. The text is beautifully illustrated with many photographs of Wilfred Heaton, his family, associated locations and sundry luminaries of the brass-band world.

This book will be essential to all enthusiasts of brass-band music and British music in general. It will serve as a source book for anyone who wishes to get to know Wilfred Heaton’s work. Programme note authors and commentators will find it an encyclopaedic treasure trove. Social and church historians will appreciate the discussion of problems that can be caused when conservative (with a small ‘c’) dogma meets artistic freedom.

John France

Availability: world of brass