Lee R. Kesselman (b. 1951)

Would That Loving Were Enough

HAVEN

rec. 2024, Blue Griffin studio The Ballroom, Lansing,USA

Sung texts with English translations of the Japanese and Italian lyrics enclosed

Reviewed as download

Blue Griffin BGR675 [67]

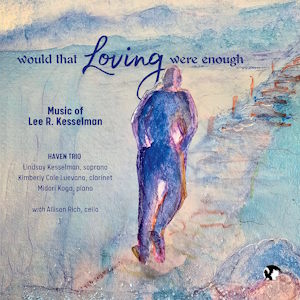

Lee Kesselman, now in his mid-seventies, has a long career as composer of, especially, vocal music. He is no stranger to the record catalogues, but this seems to be the first CD entirely devoted to his music. It is a miscellaneous collection, primarily written for the HAVEN Trio, consisting of his daughter, soprano Lindsey, Kimberly Cole Luevano, clarinet and pianist Midori Koga, with guest artist Allison Rich, cello appearing in a couple of numbers. All the works on this disc are from the last two decades, the most recent being from 2021.

Kesselman has a deep interest in Japanese music and literature, and opens the disc with probably the best-known folksong, Sakura, which means cherry blossom, the Japanese national flower, seen everywhere in Japanese art. It is a beautiful song, its age unknown, but it is supposed to have originally been intended for the bamboo flute. Kesselman’s arrangement for piano and clarinet is sensitive and it is performed lyrically and beautifully.

The eight movement suite Ashes & Dreams collects poems, mostly by anonymous poets are either in form of haiku or waka. Haiku poems are common also in the West, while the much older waka dates back to the early middle ages. They are structured differently and waka poems were traditionally written by women and haiku by men. Haiku explains or define emotions or deal with philosophical subjects or try to capture nature, waka captures or expresses emotions. Whether this means that there is a genetic difference – that women are more emotional – is of course open to debate. Kesselman’s music doesn’t give any clues – as far as I can hear – and there is no trace of influences from Japanese folk music. On the contrary, it is harmoniously knotty and rather aggressive, apart from the instrumental prelude. I have returned to these songs several times, but they have not opened up. They are not uninteresting, rather thrilling – but they leave me blank. They make heavy demands on the soprano, the tessitura is high and Lindsay Kesselman sings with great intensity. She is really impressive, as she is elsewhere, too.

Piangerò is a quite different matter. Cleopatra’s aria from the third act of Handel’s masterwork Giulio Cesare is of course one of the gems of the opera literature, and I can understand that Kesselman wants to return to it – to reimagine it or, as he writes in the booklet, to ‘free ourselves to use present language to cast masks upon music of the past.’ He refers to Bach, Handel, Mozart and Stravinsky as models without specifying, but I immediately think of Mozart’s modernizing of Handel’s Messiah and Stravinsky’s pasticcio on Pergolesi’s music in Pulcinella. Everybody is of course legally free to use Handel’s music; the question is: how valid is it to aim to make the composer’s music more accessible to today’s audiences? In Mozart’s time, audiences had a one-track mind: almost all the music that one heard was newly written in the style that was predominant and everything else was passé. Most of what we hear today – within the realms of what we call ‘classical music’ – is old and at least more advanced listeners are familiar with historical periods and genres, while contemporary classical music is accepted by only a minority of the concertgoing public. Handel’s music doesn’t need promotion, but I believe that Kesselman simply loves it just as much as I do, and wants to embrace it and make it his own. This is understandable, and his reinterpretation is interesting – and not too radical. I listened to it with pleasure, and I hope Lee will excuse me if I say that in the last resort I still prefer Handel’s original.

The original that follows is Lee Kesselman’s own, and this is a hit in every respect. It is a scene or monologue from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night; and Kesselman describes it thus in his notes: ‘Viola, in her disguise as Cesario, carries this message of love from Orsino to Olivia. While Orsino has only sent her as surrogate, Viola’s passionate declaration speaks of the intense devotion, agony, and complete surrender that Viola imagines true love to be. Viola (in her disguise as Cesario) delivers this speech after Orsino has sent her to carry his messages of love to Olivia. In this speech, however, Cesario sets aside the prepared messages and instead tells Olivia what he would do if he were in love with her.’ Without going into details, I have first praise the sensitive and inventive accompaniments by piano and clarinet; in particular, the clarinet’s comments function as a second voice, so expressive and so perceptive. The music vacillates between calmness and anxiety, intense outbreaks and beautiful lyricism. There are passages of blues feeling and the end of the scene is an aria of immense beauty that concludes in a soft pianissimo. I wish the silence afterwards had lasted longer to allow some contemplation.

This scene is an independent piece of music, but it is followed by an aria from an opera-in-progress by Kesselman to a libretto by James Tucker after Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s novella The Yellow Wallpaper published in 1892. It is written as the secret journal of a woman, sentenced by her husband, John, to a country rest cure to remedy her “nervous condition.” Her husband and doctor refuse to allow her to express herself through writing and confine her in a bedroom with a garish, yellow-patterned wallpaper. Over time, she creates her own reality in her journal, discovers a feminine alter-ego behind the wallpaper and descends into insanity. The concert-aria, as it is labelled at this stage of the progress, is a weird portrait of a woman bereft of her freedom. Kesselman here introduces the cello as the instrumental counterpart. It is both soothing and threatening. For long stretches the accompaniment is sparse and hesitant, but it intensifies as the panic grows. In the end, after her painful fit of rage, she is exhausted and downhearted, singing with pale voice :

How I long to forget these troubles

And make John proud of me again.

But who will help me find myself?

Who can, who will set me free?

This is followed by the last comment from the cello: a long, very long soft tone that finally dies away, whispering Nobody! It is an utterly touching conclusion of an utterly moving aria. I do hope that this opera-in-progress will be finished in due time.

The title of the short song cycle Would that loving were enough is also that of the whole album, which I interpret as indicating that Kesselman attaches special importance to it, especially since he himself wrote the poetry decades ago. It tells the story of a relationship through four facets. I prefer a wine of some complexity is melodically attractive, like a romantic ballad, gently swinging. You lie-a-bed has the same characteristics, only it is more distinguished swingy. I wish that loving were enough contrasts to the two previous songs and is melancholy and recessed, but there is a bluesy feeling throughout. The final song, That’s a wrap, is the scherzo of this cycle: up-tempo, rhythmically jagged and showy. It is quite naughty, in fact, and the general atmosphere is jazzy. Readers who are hesitant to contemporary music could safely begin here and will undoubtedly find that it is easily digestibly.

The encore is even more approachable. Stairway to Paradise is a song written by George Gershwin in 1922 for the Broadway musical George White’s Scandals. As was so often the case, the lyrics are by his older brother Ira, but for some reason he wrote them under the pseudonym Arthur Francis. The liner notes state that ‘the song is an anthem for the joys of dancing in the Roaring 20’s, where each step is a step on the joyful staircase to heaven as well as the ever-changing dance steps of the day.’ This is truly light-hearted swing at its best. Besides the relaxed singing, we are also treated to a Goodman-influenced clarinet solo. It makes a lovely conclusion to a fascinating and many-sided programme, that should convert some sceptical listeners to give contemporary music a listen.

Göran Forsling

Availability: Blue GriffinContents

Sakura [8:45] Japanese folksong arr. Lee R. Kesselman (2018)

Ashes & Dreams Music by Lee R. Kesselman (2016)

1. Prelude (2:48)

2. Wakaishu ya (1:23)

3. Omoitsusu (2:16)

4. Te no ue ni (0:54)

5. Kagiri naki (1:46)

6. No o yaku to (1:56)

7. Yume ni dani (4:16)

8. Nishi no sora e (2:50)

Piangerò (8:45) Music by Lee R. Kesselman (2012) Based on music by George Frideric Handel and lyrics by Nicola Francesco Haym from the opera Giulio Cesare

Make me a willow cabin (9:39) Music by Lee R. Kesselman (2014) Lyrics by William Shakespeare, from Twelfth Night

How I hate this room (10:39) Music by Lee R. Kesselman (2007) Lyrics by James Tucker after Charlotte Perkins Gilman from The Yellow Wallpaper

Would that loving were enough Music & Lyrics by Lee R. Kesselman (2021)

I. I prefer a wine of some complexity (2:59)

II. You lie-a-bed (4:43)

III. I wish that loving were enough (3:57)

IV. That’s a wrap (2:22)

I’ll build a stairway to Paradise (2:40) Music by George Gershwin Lyrics by B. G. De Sylva & Ira Gershwin arr. Lee R. Kesselman (2018)

Performers

Lindsay Kesselman (soprano), Kimberly Cole Luevano (clarinet), Midori Koga (piano); Allison Rich (cello)