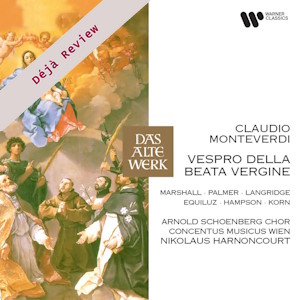

Déjà Review: this review was first published in February 2009 and the recording is still available.

Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643)

Vespro della Beata Vergine (1610)

Margaret Marshall (soprano), Felicity Palmer (mezzo), Philip Langridge (tenor), Kurt Equiluz (tenor), Thomas Hampson (baritone), Arthur Korn (bass)

Tolzer Knabenchor, Choralschola der Wiener Hofburgkapelle, Arnold Schoenberg Choir

Concentus Musicus Wien/Nikolaus Harnoncourt

rec. live, 8-9 July 1986, Graz Cathedral, Austria

Originally reviewed as Das Alte Werk 2564694648

Warner Classics 9029677129 [2 CDs: 95]

This disc was recorded some two or three years after the ground-breaking recording by Andrew Parrott, but it could not be more different. Like Parrott, Harnoncourt has recorded the Vespers in the context of a religious service, with the relevant antiphons to the Psalms and to the Magnificat. Harnoncourt’s recording was made live, in Graz Cathedral, and uses all of the associated spatial possibilities. The reading is derived from his examination of the surviving part-books and how the various instrumental parts are notated there; for example for different movements the cornett parts are notated in different part-books. Though Harnoncourt provides an interesting essay in the CD booklet discussing these issues, he does not make any comments about how he decided on the size of his forces.

This is where Harnoncourt starts to differ from Parrott. Parrott uses a small vocal ensemble, whose singers double as soloists, with most movements done one to a part. Whereas the choral forces used here include the Tolz Boys Choir, the Choralschola der Wiener Hofburgkapelle and the Arnold Schoenberg Choir. Add to this a sextet of soloists: Margaret Marshall, Felicity Palmer, Philip Langridge, Kurt Equiluz, Thomas Hampson and Arthur Korn. These are joined by an instrumental group of some three dozen musicians. This means that Harnoncourt and his forces produce a large-scale sound in the bigger pieces. The soloists are all mainstream oratorio/operatic soloists whose repertoire included an element of early performance, rather than the period performance specialists used by Parrott.

At this point we must move towards discarding the Parrott version as a comparison. The two are just too different and their aims too dissimilar. Instead we will have to ask ourselves whether Harnoncourt succeeds on his own terms. Before we completely discard Parrott’s account, we should note that Harnoncourt ignores Parrott’s scholarship and performs the Magnificat and Lauda Sion using high pitch.

Performing with relatively large forces in the apparently resonant acoustic of Graz Cathedral seems to have encouraged Harnoncourt to be relatively sedate with his tempos. Granted, the instrumental interludes have the sort of fizz and bounce that one would expect. But for much of the time the massed choral sections sound positively stolid, without any of the rhythmic impetus that I would have expected. It does not help that the slower speeds and the acoustic tempt Harnoncourt into some positively romantic tempo fluctuations.

This sogginess fatally affects the whole performance. Different movements are recorded in different parts of the cathedral, thus giving us a variety of acoustic effects. Fatally, the antiphons are highly recessed; they seem to be recorded at a far greater distance from the microphone than the rest of the disc. Time and again Harnoncourt’s direction allows the music to rest and pause when we want it to move on swiftly. The whole piece has a stop/go feel which means produces an effect where it seems to add up to less than the sum of its parts.

The CD booklet fails to make it clear who sings what, but the boy’s choir definitely sings the soprano part in the Sonata sopra “Sancta Maria”. Harnoncourt encourages them to belt out the vocal line, singing the notes with an attack and separation that would seem more suitable in Stravinsky than Monteverdi. You lose any sense of the vocal part being a cantus firmus around which the sonata is constructed.

In the other movements where there are vocal lines surrounding a cantus firmus, the cantus firmus is sung by the choir and the other vocal lines are taken by soloists. These soloists are distinctly spot-lit, in a manner more suitable to a later period, with the cantus firmus sung quietly in the background.

In some of these movements, you get the distinct impression that some of Harnoncourt’s speeds were decided by the speed at which the soloists could sing the faster sections of the music. Both tenors have very distinctive vibratos which seem entirely out of keeping in this music. Langridge and Equiluz acquit themselves well, but both have moments when their faster passage-work is obscured by their vibrato. This is not so much a problem for Margaret Marshall and Felicity Palmer, though neither approaches the delicacy that some other later singers have brought to the parts. Thomas Hampson and Arthur Korn have the disadvantage of having to sing the Magnficat in its high key, so we should perhaps not complain too much that the result sounds rather operatic.

If you are looking for a large-scale period performance of the Vespers, then frankly I don’t think this is the version for you. If you really must have that sort of version, you would do well to investigate John Eliot Gardiner’s second recording, made in 1991. It bears little resemblance to anything that Monteverdi might have heard. Taken on its own terms it works far better than Harnoncourt. This disc, with its unstrung tempos and slack pacing entirely fails to convince.

Robert Hugill

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free