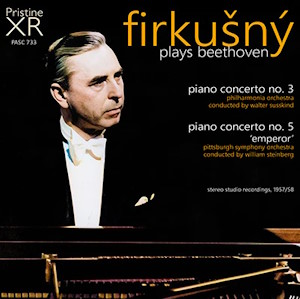

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Piano Concerto No.3 in C minor, Op.37

Piano Concerto No.5 in E flat, Op.73 “Emperor”

Rudolf Firkušný (piano)

Philharmonia Orchestra/Walter Susskind (No. 3)

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra/William Steinberg (No. 5)

rec. 16 June 1958, Abbey Road Studio No. 1, London (No.3), 26 October 1957, Syria Mosque, Pittsburgh (No.5)

Pristine Audio PASC733 [72]

Rudolf Firkušný was born in a village near Brno in 1912. As a very young boy he was mentored by Janáček and as he grew he was state sponsored to study in Berlin with Schnabel and in Paris with Cortot. When the Nazis moved into the Czech lands in the Spring of 1939 he fled, ending up in America where he settled.

Firkušný’s discography is interested and varied. He recorded first for American Columbia, then for the English label on both the Capitol label and Columbia itself. He then made records for Westminster, Decca, Deutsche Grammophon, Vox and RCA. Although he recorded the Dvořák concerto at least four times, the number of concerti we have from him on record is not as many as you would think. He only ever committed these two concerti of Beethoven to vinyl, for instance, so their release here on Pristine is welcome.

Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.3 was available pre-war on eight sides of shellac as HMV DB1940/4 and featuring Firkušný’s erstwhile teacher Artur Schnabel. It was made in 1933 at Abbey Road with the LSO and Malcolm Sargent. During the war, HMV recorded a new version with Solomon and the BBC SO under Boult in the wartime safe haven of Bedford Grammar School (DB 6196/9). In 1950, Benno Moiseiwitsch set it down with the Philharmonia and Sargent and HMV put this out on its cheaper plum label records (eight sides again: C4160/3). With the advent of the LP in the 1950s, we had more versions of this cherished work from Wilhelm Backhaus on Decca (VPO/Böhm), Edwin Fischer directing the Philharmonia himself from the keyboard (a dinky little 10-inch record HMV BLP 1063) and the Russian Emil Gilels recorded in Paris with Cluytens. A game-changer arrived in 1958 with the stereo release of Solomon’s second version with the Philharmonia and Herbert Menges recorded a couple of years before in Abbey Road again. There were several other versions, too, including Rubinstein but these were the performances I believe most British collectors would have been familiar with as Firkušný went into the studios to make his record in June 1958 with the Philharmonia under fellow Czech émigré Walter Susskind.

From the exposition of the material in the orchestra you will be immediately struck by the bloom and richness of the sound. There is no trace of surface noise from the 66-year-old grooves, yet no hint of filtering or recession at all. Winds come through the orchestral foundation Beethoven sets up vitally and with brightness. There is a florescence in the tuttis and the early stereo picture is natural and proportional. Susskind, just a year younger than the 46 year old Rudolf Firkušný, shows his mettle and pedigree in the accompaniment throughout. He had already worked as chief of the Scottish Orchestra and the Melbourne SO and had just been appointed principal in Toronto.

The EMI engineers capture the piano less well than the orchestra. This was a similar story in the same studio two years before for Solomon in his superlative recording. I am unsure why this is. The instrument just feels duller than it should when compared with the colour the orchestra provides. It feels as if Pristine have brightened the piano tone a little and this is mostly successful. As an aside, we should say the English engineers did a better job than the French ones for Gilels whose piano sounds very small scale (the performance is magnificent nonetheless).

The first subject is full of unease and portent and the second calm and beautiful. This is the material the soloist works with when he enters. Firkušný is fluent in his approach and he sounds harmonious alongside his orchestral colleagues. His cadenza (Beethoven’s own) is very well done. I don’t think anybody would expect me to extol his account as being above those versions I mentioned that preceded it but at least we can hear it now in probably the best sound yet.

The slow movement in the distant land of E major is a wonderfully gentle and serene largo. Firkušný is poetic and eloquent in his phrasing of this profound music. Beethoven asks for a lot of pedal in this movement (further blurring the early stereo sound) but even here the sound comes through really well in this transfer. Firkušný takes just under nine minutes for the slow movement – quite a lively pace actually; Solomon in 1956 was almost two minutes slower. Slowest of all was Schnabel in that first magnificent set.

The rondo is despatched with finesse. Some stylish wind playing from the Philharmonia is in evidence and our soloist is similarly stylish in his playing throughout, as Beethoven takes us through a myriad of light and darkness in the progression of this often unsettling round. Can anyone listen to the way Beethoven turns the theme around (at 8:02), banishing the shadows away for good, and not smile at this genius?

The record made very little splash at the time. Released on the UK in mono on the Capitol label then transferred to the cheap MfP (Music for Pleasure) budget line it did appear on CD in EMI’s Seraphim series (in stereo) but none of these is exactly mainstream.

For record buyers in the 1950s, budget constraints may have meant they had to choose just one Beethoven concerto to own. Many would have gone for the Emperor and most would say this is indeed Beethoven’s finest example. The record catalogues were full of wonderous treasures in both the pre-war era and onwards through the 1940s and into the LP age. HMV offered Schnabel (three times), Edwin Fischer (twice) and Moiseiwitsch. English Columbia had two versions with Walter Gieseking and the underrated Dennis Matthews version with the Philharmonia and Susskind on cheap dark blue label 78s. On Decca the legendary Clifford Curzon had set down a performance on 10 sides of shellac with the LPO and Szell and followed it in 1957 with an even finer account in Vienna with Knappertsbusch, a John Culshaw production (SXL 2002). You could have Backhaus with Clemens Krauss, also employing the VPO. What names; what times – what joy for us that their art lives on in these records.

Solomon’s version recorded in April 1955 and released as HMV ALP1300 was unfortunately in mono but that is the only unfortunate thing about it. For me, this is and always has been the cream of the crop. It was recorded in Abbey Road with the Philharmonia under Herbert Menges.

Rudolf Firkušný recorded the piece three times: here in Pittsburgh, with the RPO and Kempe in 1964 and also for Decca in 1973 with the New Philharmonia and Uri Segal, who some readers may remember led the Bournemouth SO for a brief period between Paavo Berglund’s tenure and the arrival of Rudolf Barshai. This last recording resurfaced last year after many years in an Eloquence boxset devoted to Firkušný.

This first recording was made in the Syria Mosque in Pittsburgh in October 1957 with the Pittsburgh SO under William Steinberg. EMI collected most of Steinberg’s EMI/Capitol recordings made in Pittsburgh and put them in an Icon box years ago. The piano concerto here is included there but it is nice to have this new edition.

Again, Andrew Rose has remastered this recording and has produced a clean balanced and natural sound. The piano sounds mostly clear (although it can get a little muddy in its lower registers) and there is no compression; indeed, it feels airy. It has to be said the EMI sound is absolutely fine as well. Firkušný gives a thoroughly satisfying account of the long first movement. Although the music lies nicely under the hands, it cannot be said to be a comfortable assignment for a soloist. It is such a heroic and intense movement and there is much variation in effect. I think Firkušný produces an account that can be ranked in the middle-tier. He can turn on the grand manner when the music asks for it but I feel he is happier in the more thoughtful, gentler periods of the span. Together, soloist and orchestra set a nice lively pace through the movement avoiding the unnecessary and unwritten changes to tempo many pianists seem to adopt in this work. As an imposing, even monumental example of symphonic writing, this movement has probably never been more impressively interpreted than by Edwin Fischer and Furtwängler in 1951.

At the time Gramophone said of the new Firkušný record: “the expansive pace of the Adagio isn’t quite steadily sustained”. I disagree and for me this lovely nocturne type idyll is the pearl of this performance. Firkušný is delicate and dreamy but not at all sentimental. His is a serene version I will happily return to. Nothing, however, can undo the spell Solomon cast on me all those year ago when I first heard his incomparable version of this adagio.

There is a bridging passage from slow movement to rondo and from here all is exuberance and joy. Firkušný is very imposing (too much so?) in his dynamics. I can’t hear any difference between his forte and his fortissimo but apart from this he is good and he certainly captures the mood of the music. There are places in this finale where the hushed string accompaniment is barely audible but this will be down to the source material Pristine had to work with. In the main, the sound is impressive given the vintage.

I am glad Pristine resurrected these records and have given them a new lease of life. My comparative notes highlight lots of other recordings that preceded these. Of course, in the decades since there have been many others; indeed, a year or so later the great Beethovenian Claudio Arrau set down his concerti with Alceo Galliera and these are essential listening. The notes from Pristine enticingly talk of more from Firkušný to come. I hope this will be from this EMI/Capitol era, as there are some gems not generally available that will be good to hear again.

Philip Harrison

Availability: Pristine Classical