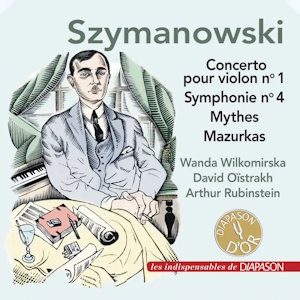

Karol Szymanowski (1882-19137)

Violin Concerto No. 1 Op. 35 (1916)

Mythes for violin and piano Op. 30 (1915)

Symphony No. 4 – Symphonie Concertante Op. 60 (1932)

Mazurkas Op. 50 Nos. 1, 2, 3 and 6 (1924-5)

Wanda Wiłkomirska (violin: concerto)

David Oistrakh (violin: Mythes)

Vladimir Yampolski (piano: Mythes)

Arthur Rubinstein (piano: symphony, mazurkas)

Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra/Witold Rowicki (concerto)

Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra/Alfred Wallenstein (symphony)

rec. 1953 (symphony), 1958 (Mythes), 1961 (concerto, mazurkas)

Diapason 739933 [72]

Szymanowski’s first violin concerto is a magical, intoxicating score, and the work which first persuaded me that this was a composer to follow. It is one of the key works of his second period, his impressionist period, and in it an idiom which owes something to the Ravel of Daphnis et Chloé, something to the Stravinsky of The Firebird and something to Scriabin, is forged into something wholly distinctive and glittering. The composer worked out the solo line in collaboration with his violinist friend Pawel Kochánski, who also wrote the cadenza. This solo line is at times very demanding technically, but display is not its main purpose: characteristically the violin soars above the orchestra or provides a rhythmic motif against it. The work is in one movement and it may at first seem wholly rhapsodic but, as Christopher Palmer pointed out in his book on the composer, it is actually tightly constructed.

I first heard this work in the recording reissued here, made by Wanda Wiłkomirska with Witold Rowicki conducting the Warsaw Philharmonic. Wiłkomirska had a distinguished career in her native Poland and later internationally, and this work was clearly close to her heart. She played it with this orchestra and conductor at the inauguration of the rebuilt Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall in 1958, and this recording followed three years later. She has a wonderful sense of fantasy and adventure in her playing of the solo line, while adhering strictly to the score. Rowicki had built his orchestra up from nothing after the Second World War and made it a powerful and expressive instrument: the filigree detail and subtle orchestral colours are well realized here, and the recording, which first appeared on Polskie Nagrania, is surprisingly good for its date.

Next we have the three Mythes for violin and piano. These come from the same period as the concerto and share its atmosphere, with a piano part whose layout and general character owes a good deal to Ravel, specifically Ravel’s piano triptych Gaspard de la Nuit. This seems to have had a great influence on Szymanowski, who also liked to write in triptychs during this period: as well as these pieces, there are the sets of Métopes and Masques for piano solo. The three pieces are all character ones: La fontaine d’Aréthuse has a shimmering opening which derives from Ravel’s Ondine. Narcisse is a narrative in a modified sonata form, while Dryades et Pan is a scherzo, which, among other things, uses quarter tones and leads to a wild dance. If the writing at times suggests Bartók, the influence goes the other way round: Bartók heard and admired these pieces before writing his own violin sonatas. Wiłkomirska recorded these pieces too, but I have not heard her version. Instead, we have that by David Oistrakh, in the only occasion on which he recorded all three of them; this version first appeared posthumously on Testament in a mixed programme. His playing is, as one would expect, poised and supremely polished. Yampolski is on top of the very demanding piano part and the result is ravishing. The recording is perfectly acceptable. Incidentally, Oistrakh recorded a good deal of other Szymanowski, and I welcomed a reissue of his version of the first violin concerto a few years ago (review).

Then we have the work listed on the front of the label as Syzmanowski’s fourth symphony and on the back as Symphonie Concertante. Both titles are valid. This comes from the composer’s third period, in which he had left behind the impressionism of his middle period for a harder-edged idiom owing a good deal to Polish folk music, which he had recently come to appreciate. He wrote a work which would be immediately appealing to an audience and in which he could play the solo part. He was a good pianist, and there are some challenging passages in octaves, but he was not a bravura pianist in the manner of Rachmaninoff or Prokofiev and he did not share their interest in technical display. This is a neoclassical work, in the traditional three movements for a concerto, and it is full of good tunes and lively rhythms. Szymanowski did indeed play the solo piano part at the premiere, but he dedicated the work to his friend Arthur Rubinstein, who plays it here. Rubinstein is magisterial, as one would expect, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic seem to enjoy their outing into unfamiliar territory. Some allowance has to be made for the recording, made by RCA, which is congested at climaxes, and I noted that the important E flat clarinet line is not as clear as it should be. Still, as this is Rubinstein’s only recording of the work, it should be cherished.

Finally, as a kind of encore, we have Rubinstein’s performance of four of the Op. 50 Mazurkas. These derive both from the example of Chopin and from Polish folk music and were also dedicated to him. These are nicely done, and applause is included.

This reissue is very convenient but there is no booklet and no documentation other than what I have supplied at the top of this review. Szymanowski fans will want or have already more modern recordings of all these works, but these versions are classics and their return is to be welcomed.

Stephen Barber

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free