Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565 (transcr. Busoni, 1888)

Prelude and Fugue in D major, BWV 532 (transcr. Busoni, 1899)

Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

Ten Variations on a Prelude of Chopin (1885 rev. 1922)

Sonatina (1910)

Sonatina seconda (1912)

Fantasia Contrappuntistica for two pianos (1922)

Peter Donohoe (piano), Karl Lutchmayer (piano, Fantasia)

rec. 2024, Wyastone Concert Hall, Monmouth, UK

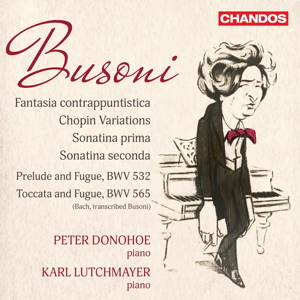

Chandos CHAN20342 [83]

Busoni’s Fantasia Contrappuntistica, his largest solo piano work, has really come into its own. I have reviewed three recordings of it in almost as many months. Moreover, each has been of a different version of the work, but more on that later. The Fantasia is here the culminating work in a skilfully planned recital, which begins with some of Busoni’s most accessible works, those based on Bach, and ends with some of the most advanced.

We begin with two Bach transcriptions, in fact the first and the last of Busoni’s transcriptions of Bach’s organ works, though in reverse order. Both of these immediately raise the question of authenticity. The issue is not the ethics of transcribing organ works for the piano: Bach frequently transcribed his own works. As for the use of the piano, Charles Rosen pointed out that Bach expected players to use any keyboard instrument available, which might have been a clavichord, harpsichord, organ, or indeed, in his later years, a piano. Busoni has transcribed these works in the spirit of Liszt’s own transcriptions of Bach’s organ works, in a massive late Romantic style. Clearly, an authentic performance of Bach-Busoni is going to be in that style and not in the historically informed manner in which Bach and other baroque composers are usually performed nowadays. This Donohoe offers. Indeed, if this version of the celebrated D minor Toccata and Fugue sounds so rich it suggests Stokowski’s orchestral version, then we should remember that Stokowski based his version, not on the organ original, but on Busoni’s version. (Later, Ronald Stevenson completed the circle by transcribing Stokowski’s version back for piano.)

Then we have Busoni’s Variations on a theme of Chopin, specifically the C minor Prelude from Chopin’s Op. 22 set. The original version of this work was one of Busoni’s earliest works, written in 1884. This followed the theme with eighteen variations and a fugue. In 1912 Busoni reworked it, cutting eight variations and the fugue, though reusing some of the latter in the new finale. He also lightened the texture, making it less Brahmsian. The variations are very free and the original theme often disappears completely. One variation is marked En carillon and another Hommage à Chopin Tempo di Valse and the whole is a clear demonstration of how Busoni rethought earlier composers.

Next we have the first two of the set of six Sonatinas, which Busoni composed between 1910 and 1921. This I consider the most important of the several cycles of piano works that he wrote. Their title is accurate in that they are not particularly long – each is a single movement. However, the writing is often harmonically and polyphonically rich and also challenging to play and these are not beginners’ pieces. The two we have here are also the most adventurous. The first starts out deceptively gently and then we have what is in effect a set of variations, which get progressively more complicated. They feature cross-rhythms and polyrhythms, the whole-tone scale and a good deal of virtuosity and taking us to some very strange places before subsiding to a quiet ending. The second sonatina is even stranger, beginning with a theme in single notes which is subjected to constant variation and elaboration. There is no key signature or time signature and there are some amazing passages. Busoni was to incorporate much of this work into his opera Doktor Faust.

Finally, we reach the Fantasia Contrappuntistica, and I need to clarify my opening remark about versions. This work is based on the final, unfinished fugue from Bach’s Art of Fugue and also incorporates the combination of the three themes which Bach expounds with that of the motto theme of the whole of the Art of Fugue. Busoni was shown this combination by Bernard Ziehn during his time in New York in 1910. He devised his own continuation and conclusion, including much material of his own as well as Bach’s, and titled the work Grosse Fuge. This was the first version and it has been recorded by Holger Grosschop in his collection of Busoni transcriptions on Capriccio. However, later that year and back in Europe, Busoni revised the work, adding as an introduction a version of a Bach chorale prelude he had already used in his set of piano Elegies. He titled this second version Fantasia Contrappuntistica and said that this was the edizione definitiva. This is, indeed, the version which is most commonly played and there are many recordings. I was recently very impressed by the reissue of that by Alfred Brendel, one of his earliest recordings (review). In 1912 Busoni issued a third version, an edizione minore, which has a revised opening and a simpler conclusion. This is a rarity, but it has been recorded by Wolf Harden in volume 11 of his complete Busoni series (Naxos 8.573982). Then in 1922 Busoni arranged the work a fourth time, now for two pianos, and this is what we have here.

Although in all these versions, Busoni incorporates Bach’s unfinished work, he does not take it over unaltered. He makes cuts and adds chromatic elaborations and variations in his own chromatic and mysterious idiom. This fourth version has more of these than the edizione definitiva and it also combines the versions of the introductions and has various other improvements but also more cuts. Busoni did say that he intended to make yet another version for solo piano, into which he would incorporate the improvements from the two piano version, but he did not live to do so. This has now been done by Victor Nicoara, and I think this version should become the standard solo one (review). Be that as it may, the two piano version is very satisfying: not only do we get the improvements Busoni made to the earlier versions but the use of two players and instruments clarifies the polyphony and also allows octave doublings of some lines. I also noticed that Donohoe and Lutchmayer were not averse to adding a few thoughts of their own, not in the score, but these are entirely in the spirit of the work.

I had not greatly cared for Donohoe’s previous Busoni disc, though I find I was in a minority there (review ~ review). This one I like much more. Donohoe brings the same formidable technique but, or so it seems to me, more subtlety and refinement, very necesssary in the Fantasia where there is a temptation to bang away too hard at the relentless polyphony. Lutchmayer, of whom I had not previously heard, proves an adept partner in this work. There are notes by the conductor and Busoni expert Antony Beaumont, the recording is good and altogether this is a worthwhile contribution.

Stephen Barber

Buying this recording via the link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.