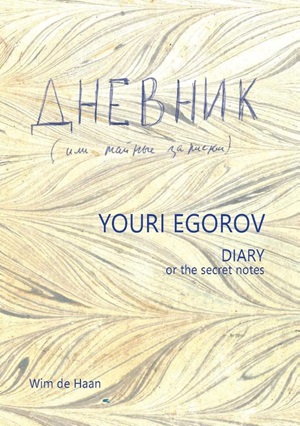

Youri Egorov: Diary, or the secret notes

Edited by Wim de Haan

Published 2024

296pp. Softcover

ISBN 9789090393520

Private release

Soviet classical pianist Youri Egorov (1954-1988) began keeping a diary in 1986 and continued it until his untimely death two years later on 16 April 1988. Diaries had always fascinated him, especially that of Russian writer Ivan Bunin. The diary enabled the pianist to pour out his soul in a frank and honest way. It wasn’t the first time he’d committed his personal thoughts to a diary. In 1976, after receiving an invitation to perform two solo concerts in Italy, on two consecutive evenings (17 and 18 May), the pianist took the opportunity to defect to the West. He sought political asylum and went into hiding in a refugee camp at the Abbey of Farfa near Rome. Here he remained from 19 May until 15 June, from where he was sent to Brussels, finally ending up in Amsterdam, the city he eventually made his home. During his month-long sojourn in Rome, he kept a diary charting his innermost thoughts. It remained hidden until after his death, when it was discovered by his partner, Jan Brouwer, concealed behind a photo frame. This 1976 diary was published in 2020 by Wim de Haan, who maintains the Youri Egorov website. A review of that diary can be found here.

This latest diary under review was written in Russian and translated into English by Claire Obolensky. She was the pianist’s best friend. The two first met in 1975, and they remained close until Egorov’s death. Throughout the diary, he refers to her as Svetunka, and occasionally as his princess. He would allow Claire to read his diary, such was their closeness.

Conveniently laid out, the diary itself is displayed over two hundred and fifty-nine pages, with a facsimile of the original Russian on the left and an English translation on the right. There are useful, detailed and informative notes at the foot of each page.

Many colleagues are praised, like Richter “a musician(s) I appreciate”, Gilels who “had a magnificent sound, never harsh or metallic” and Horowitz whose sound he liked “it is never metallic nor harsh” He went on to praise the singing qualities in his playing. Having said all of that, he prefaces it with “he is an old, spoiled clown….”. He greatly admired cellists Lynn Harrell and Mischa Maisky, the latter he collaborated with on more than one occasion. Yet, he’s deeply critical of others, and sometimes one detects a hint of envy in his words. “Pogorelich, or Ashkenazy or Barenboim, who behave as if they were archbishops. I am just a musician (talented)”. Of Brendel, he comments that “his sound is not nice and he lacks sincerity”. Perahia and Gavrilov also get the thumbs down.

Egorov was a keen football fan, and throughout he reveals his enthusiasm for the game. Watching matches on TV was often accompanied by drinking sessions. He drank heavily now and again and savored a joint on occasions. In a diary entry of 30 April 1986 he writes: “I am drunk. I plan to make a joint with the last bit of hash I brought with me”. His drinking was frequently accompanied by a bout of depression: “My heart is heavy and I often think: God save me. I often want to cry. I am drunk……..”. All of this would regularly result in a bad hangover.

Throughout the diary, Egorov reflects on his homosexuality and living as a gay man. He’s very explicit at times, too explicit to quote here. Jan Brouwer was his partner, and the two were very much in love. Brouwer also died from Aids four months after Egorov. The pianist’s musings relate incidents meeting gays on crowded trams. Then there was a steward on an aircraft “(300% gay) doesn’t smile at me”. At a disco, he relates: “I liked two guys there. Long hair and probably gay. One of them kept looking at me all the time”.

The pianist’s death from complications of Aids in April 1988 was a tragedy. His first mention of the disease is very early on in the diary. On 27 March 1986 he remarks: “this new disease has become known as AIDS. A damned virus”. By the end of September of the same year he comments that he has lost 1 kg and this is a source of worry. By now, he’s convinced he’s contracted this “horrible disease”. From his hospital bed in February 1988 he relates how he got pneumonia, then meningitis. In an entry written on 10 February 1988 he writes; “When I die I give all my belongings to Jan Brouwer, my friend”.

A supplement concludes the book. It begins with some background on Claire Obolensky, and discusses her first meeting and the blossoming of her relationship with the pianist. There’s also an article reproduced from De Telegraaf, dated 10 February 1987, and a concert review from De Volkskrant of 30 November 1987.

I have nothing but praise for this beautifully produced diary and the sterling work of Wim de Haan in keeping the candle burning for this remarkable artist. Anyone who reads this book will come away feeling they have gained a valuable insight into the life of this truly talented musician.

Stephen Greenbank

Postscript:

The following disclaimer appears on the rear of the book by author Wim de Haan, and he has asked me to include it in the review:

Who is the intended reader of this book?

If you are interested in Youri Egorov’s music and do not need to know who he really was, this book may not be for you. Youri certainly was a very lovable person, sweet and genuinely good, but as you might be aware of, he occasionally drank (too much) and smoked hash. Furthermore, the manner he managed his life as a gay man may cause concern and take away from your listening pleasure. These points are certainly confirmed in this book. Of course, music and other musicians also came up. This book gives an unusual perspective on Youri Egorov’s life, which was filled with doubts, uncertainty, discomfort and difficult decisions.

Availability: Youri Egorov website