George Frederic Handel (1685-1759)

The Handel Project

Keyboard Suite No 2 in F major HWV 427

Keyboard Suite No 5 in E major HWV430

Keyboard Suite No 8 in F minor HWV 433

Keyboard Suite No 7 in B-flat major HWV440: III Sarabande

Suite in B-flat major HWV 434: IV Minuet (arr. Wilhelm Kempff)

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Variations and Fugue on a theme by Handel, Op 24

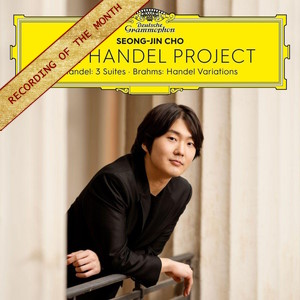

Seong-Jin Cho (piano)

rec. 2022, Siemens-Villa, Berlin

Reviewed as a digital download from a press preview

Deutsche Grammophon 4863018 [65]

I have been a big fan of Korean pianist Seong-Jin Cho since making the acquaintance of his magical 2017 Debussy disc for DG. Whilst his 2020 Schubert/Liszt/Berg recital left me a little cold, his 2018 Mozart recording was the work of a prodigious and mature talent. Even though I am still counting down the days until he adds more Mozart to his discography, this new Handel themed recital is most welcome and it doesn’t disappoint.

Handel’s keyboards suites have always languished in the long shadow of Bach’s (perhaps rightly) more celebrated keyboard music, often being relegated to fodder for student pianists. Many collectors will, like me, have an indelible association with the irresistible recordings made by Sviatoslav Richter and the chronically under-appreciated Andrei Gavrilov dividing the suites up between them. Those accounts were all about romping enthusiasm and vigorous rhythms. Cho’s conception of them is very different, as light as air and full of wit where the Russians are all about earthy good humour.

It might seem an odd epithet to apply to music making but the presiding quality of Cho’s playing seems to me to be compassion. In the minor key movements, it takes the form of a consoling, comforting manner. In the major key ones, a confiding open heartedness. These are not especially profound works, at least not in comparison to Bach, but in Cho’s hands their relative simplicity becomes a real virtue.

His manner is, probably not coincidentally, reminiscent of that other great Mozart player, Murray Perahia. The latter’s approach is a little more dreamy, Cho’s a bit more perky. Comparing them in the most famous section of the Handel keyboard suites, the variations on ‘The Harmonious Blacksmith’ that conclude the fifth suite, finds Perahia more introverted than the Korean if no less dazzling in his virtuosity. The way Cho’s fingers trip through the increasingly decorated variations is an absolute joy. Like Perahia he maintains a wonderful line between technical brilliance and elegant decorum.

That mini set of variations provides a nice link to the recital’s other big work, the Brahms Handel Variations. Whilst there is an obvious connection, this involves quite a stylistic shift even if, for his era, Brahms was quite the musical antiquarian. It might have been nice if Cho had included the suite (No 1 in B-flat) from which Brahms drew his theme but Cho’s programming of his ‘project’ is so unerring I gladly put my trust in him knowing better than me.

If I say that Cho makes light work of Brahms’ piano writing, I mean that most literally. Even the most congested of textures in the concluding fugue are light and spry. There is definitely a place for a more thunderous stampede through these pages such as Katchen gave but in its very different way this is just as exhilarating as though Brahms had been off shedding the pounds in some Austrian health spa.

Much the same spirit as informs the Handel is at work in this most unbuttoned of Brahms’ scores: dazzling finger control; a thoroughly recreative attitude to thinking about how the score can be played; and a puckish sense of humour. But above all this a sense of placid calm reigns. This is no young tyro in too much of a hurry. Initially, I thought the early variations lacked a little in cumulative momentum but Cho knows where he is going and, more importantly, how he is going to get there. The work as a whole emerges as grander and more significant. Such is the range of his fantasy that I found myself daydreaming about imaginary orchestrations of the variations in the manner of the Haydn Variations. And if all of this sounds a little too earnest, sample the Hungarian spree of Variation 14 or the hide and seek games of No 16. But Cho is at his best when Brahms lets his poetic muse take wing as in the brief twenty first variation. Cho is having nothing to do with the notion of Brahms as a gruff old bear! And even though the 28-year-old composer (the same age as the pianist) is trying his level best to come across as an old professor in the concluding fugue, Cho draws out the youthful high spirits that can’t be suppressed in the piano writing.

After the magnificence of the conclusion of that fugue, resplendent in DG’s trademark piano sound, two brief movements from Handel act as an appropriate envoi, tying up the programme neatly. Cho even allows himself the slightest soupçon of romanticism in the last track of all, the Minuet from the unnumbered B flat suite, in an arrangement by Wilhelm Kempff, like a sly allusion to the Brahms.

It will be more than obvious by now that this is piano playing of rare distinction and a major addition to a young pianist’s already illustrious recording career. Looking at the steady flow of recordings from Chandos of John Wilson and his merry band, I can only wish DG would get Cho into the studio more often but, as evidenced by this superlative recording, good things come to those who wait.

David McDade

Help us financially by purchasing from