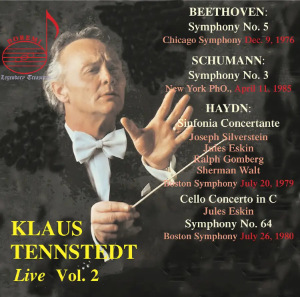

Klaus Tennstedt (conductor)

Live Volume 2

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Symphony No 5 in C minor, Opus 67 (1804-8)

Robert Schumann (1810-56)

Symphony No 3 in E flat major “Rhenish”, Opus 97 (1850)

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

Sinfonia Concertante in B flat major (1792)

Cello Concerto in C major (1761-5?)

Symphony No 64 in A major “Tempora mutantur” (c1772-3)

Joseph Silverstein (violin); Jules Eskin (cello); Ralph Gomberg (oboe); Sherman Walt (bassoon)

Chicago Symphony Orchestra (Beethoven); New York Philharmonic Orchestra (Schumann)

Boston Symphony Orchestra (Haydn)

rec. 9 December 1976, Chicago (Beethoven); New York 11 April 1985, New York (Schumann);

20 July 1979 (Sinfonia Concertante) & 26 July 1980 (Haydn Concerto and Symphony) , Tanglewood

Doremi DHR-8243/44 [2 CDs: 147]

This compilation of live broadcasts is perhaps not an obvious purchase unless one is a dedicated Tennstedt collector, but his high level of musicianship is very evident throughout. This marvellous, inspirational conductor, an impression confirmed by those who played under him, was generally more celebrated for his Mahler, Strauss and late-Romantic repertoire. When he became chief conductor of the LPO in 1978, he wasn’t completely unknown, but his appointment was a surprise to many and, as it turned out, a remarkable coup. These performances are all live broadcasts with American orchestras.

The Beethoven performance is strong, virile and clearly belonging to the older tradition of big, full-blooded, majestic interpretations. This is fine if approached on its own terms, and if one has not become too attached to the modern tendency towards leanness. The opening movement, played with repeat, is tense and gripping, while there is a subtle degree of relaxation for the lyrical second subject. To my mind the slow movement sits back a little too much – is arguably too leisurely, even bordering on ponderous, especially at the forte tuttis. Beethoven’s Con moto is neglected. Tennstedt’s indomitable overall approach is renewed in the scherzo and trio, played with great vitality. The pizzicato passage is particularly effective, though the transition to the finale ideally should be more mysterious. In the finale itself, with repeat omitted, Beethoven’s essential heroic quality is amply realised in Tennstedt’s vigorous and incisive reading. Throughout the symphony, there is no doubting his strong sense of purpose and total conviction.

Schumann’s Rhenish Symphony receives an uplifting performance, beginning with a first movement which is on the weighty side but nevertheless buoyant. Most importantly, the music’s joyful exuberance is tangible. The second and third movements are lyrical and affectionate, though the latter could have benefited from a little more phrasing – i. e. little breathing spaces. In the Cologne Cathedral movement, Tennstedt is majestic without being in the least overweight and the finale, which can easily sound sluggish, is exhilarating. It would be remiss of me not to stress this conductor’s feeling for beauty of sound, a quality which struck me many times incidentally – i. e. never seeming an end in itself. Tennstedt could not be described as an instinctive conductor of Schumann, a composer whose musical language is admirably conveyed by Hans Gál in his slim BBC Music Guide: “… his soul is in every expressive phrase he shapes”. Yet an outstanding and inspirational musician such as Tennstedt, especially in live concerts – is capable of producing such an energised and musically satisfying performance as the one recorded here.

The Haydn Sinfonia Concertante is, along with most pieces of chamber music, the kind of work which benefits from being performed by musicians who regularly play together. Here we have the principals of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, who give a most engaging performance. This is a wonderfully genial work. Simply for its existence, we have to acknowledge the significant influence of Johann Christian Bach, who was developing the sinfonia concertante genre many years before Haydn’s example. If we can ignore the voice from another radio station, we can hardly fail to thoroughly enjoy this work – one which used to be more overshadowed by Haydn’s symphonic output – in such an involved performance as recorded here.

In Haydn’s C major Cello Concerto Jules Eskin, the Boston Symphony principal of that time and for more than half a century, plays eloquently with magnificent tone. The tempo for the central movement is slow, though this is an Adagio, while the final Allegro molto is stirring without being – as in some recordings – breathless.

The Haydn symphony is an intriguing choice – unexpected repertoire for this conductor and in any case a very rarely performed work. For once, this is Haydn’s own nickname, “Tempora mutantur” being part of an epigram by the Elizabethan poet John Owen, translatable as “The times are Chang’d, and in them Chang’d are we; How? Man, as Times grow worse, grows worse, we see.” Probably this relates to the Largo. Tennstedt’s reading is thoroughly engaging and affectionate, but the slow movement will seem dreamlike to some, comatose to others. Its essential feeling of mystery is conveyed, however. This Largo, incidentally, is among the weirdest movements in Haydn’s symphonies – and there is no shortage of eccentricity in his wonderful body of work. This particular Largo does not seem to be one in which Haydn deliberately exercises his humour or relishes surprising the listener. Rather, it is a baffling movement in which expectations are constantly thwarted, phrases are left hanging and musical grammar seems to be forgotten – altogether creating an absent-minded impression, though nothing like the farcical slapstick in Haydn’s Symphony No 60, Il Distratto. Tennstedt performs the faster movements of the symphony – which also have some eccentricities – with vitality.

These recordings, rather harsh-toned, show their age. Some of the broadcasts are not helped by some distant but audible muttering – unfortunate interference from another station. Never mind! The noises are audible only when there is a rest in the music. Hopefully one becomes accustomed to, and can tolerate, inferior sound when the performances have so much to offer. There are no booklet notes.

Philip Borg-Wheeler

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free