Edvard Grieg (1843-1907)

String Quartet in G minor, Op 27 (1877-78)

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957)

String Quartet in D minor, Op 56 ‘Voces intimae’ (1908-09)

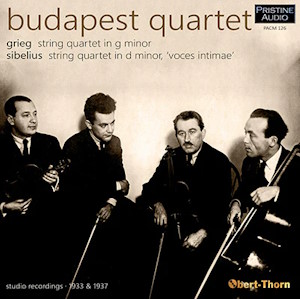

Budapest Quartet

rec. August 1933, Beethovensaal, Berlin (Sibelius): February 1937, Abbey Road Studio No.3, London (Grieg)

Pristine Audio PACM126 [61]

The Budapest Quartet was active from 1917 to 1967 with several changes of personnel and of operating base during that period. As the name implies, the initial members were all Hungarians, but these were gradually replaced by players from elsewhere in Central Europe, all then dominated by Russia, so they are often considered Russians. Hence Heifetz’s joke: ‘One Russian is an anarchist. Two Russians are a chess game. Three Russians are a revolution. Four Russians are the Budapest String Quartet.’ The makeup of the quartet for these recordings was Joseph Roisman, from Odessa in Ukraine, leader – he had previously played second violin in the quartet; Alexander Schneider from Vilnius in Lithuania, second violin; István Ipólyi, from Újvidék in Hungary and a founder member of the quartet, viola for the Grieg, but Boris Kroyt, a Jewish Ukrainian, initially from Odessa but later based in Berlin, for the Sibelius; and Mischa Schneider, the older brother of the violinist Alexander Schneider, cello.

The quartet was initially based in Budapest but moved in 1921 or 1922 to Berlin, where they remained until the Nazi threat forced a sudden departure to Paris in 1936. Although they toured a good deal, from 1938 they made the USA their base. From this time their reputation grew, and they became one of the best-known quartets active, and they made many recordings. Although they had a large repertoire, in their recordings they concentrated mainly on the core Viennese tradition.

The Grieg and Sibelius quartets are the best-known Nordic quartets and have often been coupled together. These are the first complete recordings of either. Grieg actually worked on three quartets. The first was a student work which has disappeared. The present work is his only published quartet; he began another one but completed only two movements of it. (It was completed after his death, from his sketches, by his friend, the composer Julius Röntgen; this has been recorded by the Raphael quartet. There is also a more recent completion by Levon Chilingirian, which his quartet has recorded.) Sibelius wrote three quartets in his youth but the one here, subtitled Voces intimae, is the only mature one.

The Grieg is a serious and full-blooded affair, which rather belies Grieg’s reputation as a composer primarily of attractive miniatures. There is a sonata-form first movement, a lyrical Romanze, a scherzo marked Intermezzo and a finale which, after an introduction, is marked Presto al Saltarello. The writing is very full, with a good deal of double stopping – indeed, for this reason Grieg’s first proposed publisher refused to take it. I consider it stays this side of an orchestral sonority, though perhaps only just. But it is a good work, not very characteristic of the composer.

The Sibelius is restless and disturbed throughout, and also very fully scored. It is in five movements. The first is in sonata form but quite condensed. There follows a scherzo which goes at a hell of a pace and must be very tricky to play. There follows a slow movement, marked Adagio di molto, which recalls to me the mood and some of the phrasing of the Cavatina from Beethoven’s late quartet in B flat, Op. 130. It is a measure of Sibelius’s stature that he does not collapse under the comparison. The subtitle Voces intimae (intimate voices) arises from the fact that the composer wrote these words under the three chords of E minor which occur shortly after the start of this movement. There follows a scherzo-type movement in which a clod-hopping main theme is contrasted with a second theme in fast triplets. The finale is practically a moto perpetuo, with snatches of themes tossed across the instruments against constant fast running passages.

The Budapest Quartet play with great force and confidence. The playing is perhaps slightly rougher than we expect nowadays, but full of fire and passion. Occasionally, scoops in the phrasing remind us that this is an ensemble from early in the last century. Mark Obert-Thorn has done a splendid job restoring the sound from the originals on 78s. Curiously, the Grieg, recorded in London, needs more allowances made than does the Sibelius, recorded in Berlin, though the latter is the earlier recording.

This is a historic issue, of interest to connoisseurs of quartet playing and perhaps particularly also of these two quartets.

Stephen Barber

Previous review: Jonathan Woolf (November 2024)

Availability: Pristine Classical