Antonin Dvořák (1841-1904)

Cello Concerto in B minor, Op 104 (1895)

Valentin Silvestrov (b. 1937)

Prayer for the Ukraine (2014)

Other contents after review

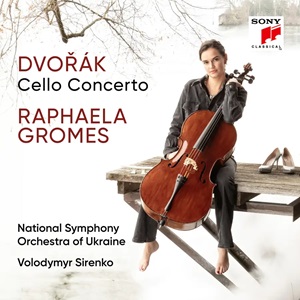

Raphaela Gromes (cello)

National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine/Volodymyr Sirenko

rec. 2024, Filharmonia Lubelska, Lublin, Poland

Sony Classical 1 98028 25742 [53]

In December 2023, the German cellist, Raphaela Gromes, gave a concert in Kyiv with Volodymyr Sirenko and the National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine. The concert is described in the booklet note – a fascinating discussion between the cellist and Ukrainian musicologist, Adelina Yefimenko – as ‘a show of solidarity’ with the Ukrainian people following the Russian invasion of their country. Gromes then wanted to continue working with the ensemble: ‘The present album is the outcome’. Gromes believes that the limited rehearsal time available for international soloists’ guest appearances has led to uniform performances that have rather lost touch with the way the Dvořák was played a generation ago, especially by Czech performers. The opportunity to record the work allowed for more rehearsal, producing ‘a genuinely shared experience that sticks closely to Dvořák’s score and to his often very brisk tempos.’ The autograph score, she tells us, is available for study, and this performance seeks closer adherence to it, the better to respect the composer’s original intentions in respect of ‘dynamic markings, rhythms, articulation markings and even individual notes’. I don’t have access to the original, of course, but my Eulenburg miniature score has served me well for more than 50 years. I was happy to settle down with it, in the company of Raphaela Gromes, to experience once again this sublime work.

Studying the score more closely than I had for a long time, I was struck, first of all, by the abundance of dynamic and other markings. It would be quite impossible for performers to respect them all, yet the soloist’s insistence on fidelity to the score rather obliged me to do a few checks. The opening of the concerto is marked Allegro, crotchet = 116. I know of few performances that are as rapid as that at the outset, and this one is no exception – they are closer to 94. The second theme, first announced by the solo horn, is almost always subjected to significant slowing down. The score is ambiguous here, only requiring something ‘a little sustained’, with the crucial extra words ‘in time’. These performers follow tradition, and slow down markedly. Following this, the orchestra initiates a crescendo that rises to a highly rhythmic, fortissimo dance-like passage. The score stipulates that this should go at exactly the same tempo as the opening of the work. But in this performance there is a sudden kick on the accelerator that produces a speed certainly faster than what is marked, and very much faster than the opening of the work. All this is to speak only of the orchestral introduction, and it can be argued that, throughout the work, these performers do not always respect the letter of the score. Yet the music flows exactly as it should, expressive yet apparently spontaneous. Only the third instance cited above came as something of a shock to this listener.

How important is this kind of analytical listening? I only bothered with it after reading of the soloist’s wish to rediscover the composer’s exact intentions through greater fidelity to the score. I believe that in such a work as this one the players are bound to respect the score’s principal indications, and that these will allow them to express the spirit of the music in their own way. Gromes and Sirenko achieve this beautifully.

Their performance of the Dvořák is quite different in some respects from others, yet is deeply satisfying and easily finds its place among the finest of them. Gromes’s playing is forthright, sometimes even uncompromising. She is equal to the score’s monstrous technical demands, and her tone is rich and beautiful, remaining so even in the loudest passages. If I occasionally wish for more quiet playing, the reading is, nonetheless, consistent and unified, so that the more inward passages are beautifully executed. The famous closing passage is very fine indeed. Gromes finds a way of injecting a spirit of defiance into the music alongside its tenderness, before leaving the orchestra, so moving and inspired on the composer’s part, to close the work without her. The orchestral playing is very fine, and Sirenko keeps a sure grip on proceedings. You won’t hear the silk-like strings of the Berlin Philharmonic, but many might think that a good thing. There is playing of much character, and a special word for the all-important first flute does not detract from the excellence of the rest of the ensemble. Sadly, though, some of the solo woodwind work is hidden because of the extremely close placing of the soloist. I seldom hear a new concerto recording where I don’t think the soloist is too close, but this is an extreme example. At her first entry, after the orchestral exposition, Gromes seems to be placed directly under our noses. We frequently seem to hear her fingers striking the fingerboard, and there are passages where the cello’s subsidiary figuration conceals more important material in the orchestra. This is my only negative observation about this disc, and others may hear it differently. For me, though, it is a pity.

All listeners will have their favourite versions of this adorable concerto. Rostropovich is unique, his astonishing technical command and total commitment to the music pretty much unrivalled anywhere. For many years I found his reading with Karajan (DG) the most satisfying, but more recently I have come to prefer a 1952 performance with Václav Talich, now available on Pristine Audio. This is, however, to compare one instance of the sublime to another. Of the innumerable other admirable versions I have on the shelves, I will cite just one, by Janos Starker and Antal Dorati with the London Symphony Orchestra on Mercury. Many more recent performances are also deeply satisfying, of course, and this one from Raphaela Gromes, which does indeed bring something new and powerful to the work, merits a place very high on the list.

The rest of the disc is made up of four pieces by Ukrainian composers, each of less than five minutes in length, originally written for other forces and performed here in arrangements by Julian Riem. Hanna Havrylets died in February 2022 on the fourth day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Tropar, then, predates that event, but Gromes’s singing line must surely be heard now as a cry for peace. The work is based on a short motif centred around the first three steps of the minor scale. Some light, and even hope, is allowed into the music when the melodic line moves away from these restricted limits, but the work ends in profound sadness, perhaps even despair.

Yuri Shevchenko also died in early 2022 and was thus spared the worst of the Russian invasion of his country. We Are is a free paraphrase of the Ukrainian national anthem. There is nothing defiant about it, neither in its original form nor in this arrangement, but many will hear national pride and confident steadfastness. I prefer to think of the work as the ‘quiet prayer’ that the booklet tells us was the composer’s aim.

Stepan Charnetsky’s Oi u luzi Chervona Kalyna (its title translated as Oh, the Red Vibernum in the Meadow is very different. Its origins are difficult to pin down, but over the years it has become a patriotic song, and one that has been proscribed by occupying forces. Charnetsky was above all a poet who, in 2005, produced a version of it to honour the Sich Riflemen, a Ukrainian military unit during the First World War. The fruit of the viburnum is a Ukrainian national symbol, and at the beginning of the song the plant is bent low, apprehensive for the future. The Ukrainian military will prevail, however, and the viburnum will stand erect and proud once again. Raphaela Gromes writes that choosing this work to close the disc was motivated by the need of ‘a more optimistic ending and a ray of hope.’

When Gromes played the Dvořák in Ukraine, Silvestrov’s Prayer for the Ukraine, placed first on the disc, was given as an encore. It was composed in 2014 as part of a larger choral work, but can be heard today as a prayer for peace. Gromes writes that at the concert, ‘many people were in tears, including the musicians on stage.’ I can well imagine how emotional that moment will have been. Gromes again: ‘Images emerge and disappear again as if in long-held breaths’. In not quite four minutes, the work’s simplicity and directness express a world of emotion and expression. The four-note phrase on which it is built has haunted my mind since I first heard it.

William Hedley

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site

Other contents:

Hanna Havrylets (1958-2022)

Tropar, Prayer to the Mother of God (2018)

Yuri Shevchenko (1953-2022)

We Are (2014)

Stepan Charnetskyi (1881-1944)

Oi u luzi Chervona Kalyna (2005)