Edvard Grieg (1843-1907)

String Quartet in G minor, Op 27 (1877-78)

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957)

String Quartet in D minor, Op 56 ‘Voces intimae’ (1908-09)

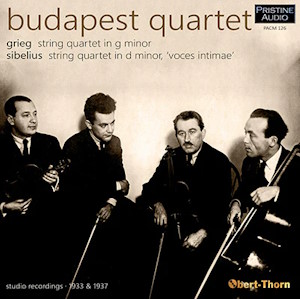

Budapest Quartet

rec. August 1933, Beethovensaal, Berlin (Sibelius): February 1937, Abbey Road Studio No.3, London (Grieg)

Pristine Audio PACM126 [61]

One of the entertaining spectator sports of recent years has been the sight of two of the remastering industry’s big beasts in accidental competition with each other. Exactly thirty years ago, Ward Marston transferred both these quartets for Biddulph (LAB098) adding Wolf’s Italian Serenade, for good measure. Here it’s the turn of Mark Obert-Thorn, though the Wolf isn’t here as it’s already been transferred on PACM113.

These were two of the great pre-war examples of the Budapest Quartet’s art. The Grieg was made with the all-Russian formation in place, in London in 1937. Though isolated movements had been recorded before this was the first complete recording, and it set a remarkable standard for ensuing groups. All the issued sides were first takes, by the way, something over which contemporary quartets can mull at their leisure. The playing is zesty, naturally phrased and virtuosic, though without seeming overbearingly so. Perhaps, to be hyper-critical of the Abbey Road recording, it draws slight attention to thinness in the upper strings – Joseph Rosman and Alexander Schneider – but there’s little or nothing else about which to complain. The Andantino fits two sides of a 78 perfectly and there are trenchant unisons in the vitalising finale. Side joins are seamless and even when one knows where they are – one fortuitously falls in the rests in the first movement – one doesn’t ‘feel’ them.

The Sibelius had never been recorded before this 1933 Berlin recording which featured the then sole remaining Hungarian, the embattled violist István Ipólyi. Cast in a Beethovenian, or proto-Bartók, arch form of five movements, with the slow movement in central position, this quartet is performed almost as well as the Grieg. It’s certainly at its most intense and powerful in that Adagio di molto which allows the Budapest Quartet to explore the full extent of its expressive depth.

There is, as customary, a one-page note from Obert-Thorn that sets the recordings in context.

As for the transfers, these new ones are more vivid and bite more viscerally than the older remasterings by Ward Marston. The Victor ‘Gold’ sets used have been transferred at a rather higher level than the copies Marston used, whilst preserving such surface noise as there is, and I can’t swear to it, but they seem to be slightly better pitched.

Jonathan Woolf

Availability: Pristine Classical