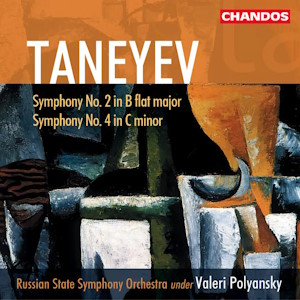

Sergey Ivanovich Taneyev (1856-1915)

Symphony No. 2 in B flat major (1877/78?)

Symphony No. 4 in C minor (1898)

Russian State Symphony Orchestra/Valeri Polyansky

rec. 2001, Grand Hall of the Moscow Conservatory

Presto CD

Chandos CHAN9998 [75]

This disc was first issued in 2002, when it was reviewed by Rob Barnett. Now, thanks to Presto Classical, it has been restored to circulation as part of their expanding on-demand catalogue.

Teneyev composed four symphonies in all. His early Symphony in E minor was written, I believe, in 1873-74 but was unpublished in his lifetime; in fact, not until 1947. The date of composition of the Second symphony is a little uncertain – and not stated in the Chandos booklet. However, in his valuable notes David Nice says that the work “took shape just before Taneyev’s life-changing discovery of Josquin Desprez, Lassus and other masters of strict counterpoint in 1878”. So, perhaps 1877/78 is a reasonable guess. Another symphony, this time in D minor, followed in 1884, though that work also lay unpublished until 1947. What was to be Taneyev’s final essay in symphonic form, his C minor symphony, was completed in 1898.

Three of Taneyev’s symphonies were cast in four movements. The outlier is the B flat symphony, which has only three movements; it lacks a scherzo. David Nice speculates that the omission “might have been rectified if Taneyev had gone any further with the prospect of a performance in mind”. To me, the symphony as we have it seems somewhat unbalanced by the lack of a third movement and because the finale plays (in this performance) for just 7:56, whereas the first two movements take 14:54 and 13:01.

The first movement opens with a brooding introduction; the music is clothed in dark orchestral hues; David Nice draws an apt parallel with the Friar Laurence music in Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet. When the main Allegro is reached the predominant nature of the music is vigorous. I think the movement as a whole seems well argued and also well imagined for orchestra. The Andante which follows is described by David Nice as an “epic song”. The music is mostly cantabile in nature but I think two things hobble the movement to some extent. One is that, as Nice says, the melodic material is “hardly memorable”, though he goes on to say that the melodies are “impressively sustained”. I agree with him and the nature of the melodic basis of the music is something of a handicap. Add to that my sense that the movement is just too long – and particularly too long for its material. As I mentioned earlier, it plays here for 13;01; if Taneyev had shaved off about three minutes a tauter structure might have resulted. I chuckled when I read David Nice’s term for the finale; he describes it as “stout and steaky”. Actually, I think that’s a bit unfair. The music is energetic and outgoing; Nice correctly draws a parallel with Glazunov in celebratory vein. It’s the sort of music that makes its best impression if conductor and orchestra really go for it and that happens here.

Despite the reservations I’ve expressed above, I think the Second symphony is an interesting work. It may not be a ‘Great Russian Symphony’ but it’s well worth hearing, especially when played with the fine conviction that Valeri Polyansky and his orchestra bring to it.

Composed some twenty years later, the Fourth symphony represents a distinct advance in many ways. The work is cast in four movements, the first of which is marked Allegro molto. This opens very dramatically with an attention-grabbing three-note figure which will have great significance. The music that follows is big and powerful – David Nice refers to “angry chromaticism”. There’s a brief respite from the tumult at 1:14 when a waltz-like subject is heard; however, that respite is to some extent vitiated by Taneyev’s decision to employ quite dark orchestral colourings for this episode, as he does when the material reappears later in the movement. After the waltz Taneyev engages in a rigorous exploration of the three-note motif. The development section is characterised by urgency, which is all the more evident in this full-on performance.

The Adagio which follows offers welcome contrast; as in the Second symphony’s comparable movement much of the music is cantabile in nature. As was the case in the preceding Allegro molto movement, there is a good deal of dark orchestral colouring but this time that darkness takes on a rich hue. There’s a brief unsettled passage partway through but for the most part I sense a positive tone to the movement. That said, the second half of the Adagio features some typically yearning Russian lyricism. Unlike in the Second symphony, there is a Scherzo. The movement is marked Vivace and that is reflected both in the music and in this performance. The principal oboe takes a leading role within the woodwind section. You may feel, as I do, that the player’s tone is rather pinched but he or she is certainly very agile, as are the rest of the woodwinds. Indeed, the entire performance is agile and this essentially light-footed movement is a very good foil to the Adagio.

David Nice points out that in the finale Taneyev revisits material from earlier in the symphony. The music is vigorous and determined; Polyansky leads a driving performance, which comes to something of an abrupt halt with some thunderous timpani rolls. Immediately after this (6:27), Taneyev reprises the waltz that we first encountered in the opening movement. This time, however, the waltz is treated to a major-key apotheosis clad in full orchestral raiment. This paves the way for a big, celebratory finish to the symphony. To be honest, I think the ending is a bit overblown but in context that’s forgivable.

These are two most interesting symphonies. I don’t think Taneyev matches the symphonic stature of Tchaikovsky (at least in Manfred and the last three numbered symphonies) nor of Rachmaninov, but on this evidence he was far from a negligible figure. Valeri Polyansky and the Russian State Symphony Orchestra make a very strong case for both works with performances that are accomplished and committed.

The recordings were not made by the Chandos in-house team; rather, they were made by Russian producers and engineers. The sound is spacious and has good presence.

I’m glad that Presto Classical have made this disc available once again.

John Quinn

Previous review: Rob Barnett (October 2002)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free