Richard Rodgers (1902-1979)

Carousel – A Musical Comedy in Two Acts (1945)

Based on the play Liliom by Ferenc Molnar, adapted by Benjamin F Glazer

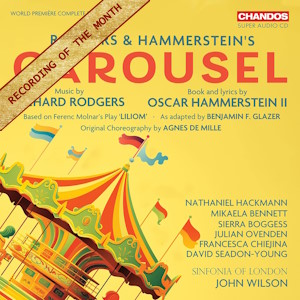

Nathaniel Hackmann (tenor – Billy Bigelow); Mikaela Bennett (soprano – Julie Jordan); Sierra Boggess (soprano – Carrie Pipperidge); Julian Ovenden (tenor – Enoch Snow); Francesca Chiejina (soprano – Nettie Fowler); David Seadon-Young (baritone – Jigger Craigin)

Carousel Ensemble

Sinfonia of London/John Wilson

rec. 2023, Susie Sainsbury Theatre, Royal Academy of Music, London

Text included

Chandos CHSA5342 SACD [2 discs: 107]

In 2023 we published a review by my colleague Paul Corfield Godfrey of John Wilson’s 2022 recording of Oklahoma! Paul’s enthusiasm convinced me that I should buy a copy and I was glad I did. Perhaps in this review of this brand-new recording of Carousel I’ll be able to return the favour and tempt Paul – and other readers, of course – into a purchase.

Oklahoma! (1943) was the first show which Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II created together. David Benedict explained in his booklet essay accompanying that recording just how ground-breaking that show was. That said, as Benedict puts it in his excellent essay in the booklet for Carousel the latter show was “the musical and dramatic zenith of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s near-two-decade-long collaboration”. When you consider that the partnership went on to produce, amongst other shows, South Pacific (1949), The King and I (1951) and The Sound of Music (1959), that’s quite a claim, not least because all three of those musicals contained at least as many, if not more, individual ‘hit’ numbers than Carousel. However, in the time I’ve been listening to this new recording, I’ve come to think that Benedict may well be right.

This recording gives us the complete score, including several numbers that have never been recorded before. It is true that adopting such a ‘complete’ approach means that there are a number of stretches of music, sometimes quite lengthy, that underpin dialogue; as an example, the track on which ‘If I loved you’ makes its first appearance lasts for 11:30 but the song itself doesn’t begin until 3:17 (when Julie Jordan sings it) and thereafter there are further passages of orchestral music underneath dialogue before Billy Bigelow has his turn with the song. At first, I wondered about this approach but I quickly realised that this completeness is essential in order to contextualise the song – and what a song it is! Furthermore, the orchestral score beneath the dialogue is anything but routine. The degree of completeness in this recording can be gauged by the fact that David Benedict mentions that the Original Broadway Cast recording of Carousel runs to 55 minutes and the film sound track is eight minutes shorter; Wilson’s recording plays for just over 107 minutes.

I learned a lot from David Benedict’s essay, not least the fact that both Puccini and Kurt Weill tried to persuade the Hungarian playwright Ferenc Molnár (1878-1952) to allow them to adapt his play Liliom (1909) for the operatic stage: one wonders what the results might have been in either case. According to the booklet credits, the play was adapted in 1921 by Benjamin F Glazer (1887-1956). I’m not entirely sure of Glazer’s role – the booklet is silent on this point – but I suspect that it was Glazer’s work (and translation into English?) that enabled the play to be a big hit on Broadway. Eventually, Molnar relented; Rodgers and Hammerstein got to work. Benedict tells us that when Carousel was first put on in a pre-Broadway performance in New Haven, Connecticut, the show ran for an epic four hours! Clearly, a musical of such Wagnerian dimensions would not be well received on Broadway and Benedict says that two songs and several choruses were excised. In addition, “almost half” of the Act II ballet (choreographed by Agnes de Mille, no less) was cut. After further surgery, following more performances in Boston, the show opened on Broadway to great acclaim in April 1945.

Of course, in a recording such as this we lose quite a lot of the ‘action’ which involves only spoken dialogue. However, David Benedict provides a really good synopsis so it’s easy to trace the action and put the musical numbers in context. Personally, I prefer the first Act where the characters and the story are being fleshed out very credibly. I find the second Act rather less credible; in the later stages of that Act, after Billy has killed himself to escape arrest, the plot verges on sentimentality as Billy returns to earth and, by finally revealing his good side, achieves redemption. Hereabouts, the plot has some loose affinities with Frank Capra’s film It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). However, Rodgers and Hammerstein just about avoid sentimentality in this last section of the score and, in fact, this recorded performance is rather moving.

The show has some great numbers. You could say that Richard Rodgers reveals his hand right at the start: he doesn’t make us wait for the celebrated Waltz; instead, he treats us to it in the Prologue. Then there’s ‘You’ll never walk alone’. This has been covered by so many artists and in so many ways over the years that, with all due deference to fans of Liverpool FC, it has become rather hackneyed. But when you experience its first appearance in Carousel, very simply accompanied and sung with unforced directness first by Mikaela Bennett (Julie) and then by Francesca Chiejina (Nettie) it emerges as the sincere and rather lovely song which its creators intended. ‘When I marry Mr Snow’ may not match the stature of ‘You’ll never walk alone’ but it’s a delightful, attractive number, especially as sung here by Sierra Boggess (Carrie). And then there’s ‘If I loved you’, which is the musical and emotional backbone of the show. It’s a wonderful song. On its first appearance Mikaela Bennett sings it touchingly and thereafter whenever the song, or just the melody, reappears it makes a fine impact; I’m rather pleased that the last thing we hear on this recording is an orchestral reprise of the song as the Exit Music, rather than the apotheosis of ‘You’ll never walk alone’ with which Act II concludes.

There are two extraordinary numbers in the score. One is the ballet in Act II. In nineteenth-century operas composers were often obliged to shoehorn ballets into their works, holding up the action just for the sake of a bit of display, whether or not the ballet was in any way relevant. The ballet in Carousel is a world away from such distracting conceits. The libretto, which Chandos reproduce, makes clear that the ballet, far from holding things up, actually advances the action. I’ve no idea what music – and, perhaps, dramatic incident – was lost in the post-New Haven pruning of the score but the ballet which survives seems to me to be taut, purposeful and musically inventive. The other significant number is Billy’s famous soliloquy towards the end of Act I. As David Benedict remarks, this sort of extended soul-searching number is fairly common in musicals these days but in 1945 it was a major innovation. It’s a very fine composition, not just in terms of the music and of Hammerstein’s lyrics but also in terms of the depths of emotion that the collaborators portray. Billy, who has learned that Julie is pregnant, contemplates fatherhood and, typically, he just assumes the baby will be a boy and he sets out his hopes for him in a blokeish fashion. But then he’s struck by the blindingly obvious: ‘What if he is a girl?’ Thereupon, the manly Billy switches to the proud, protective Billy. In this recording Nathaniel Hackmann gives a terrific and very credible performance.

There isn’t a weak link in the Chandos cast. Two of the excellent principals from the Oklahoma! recording, Nathaniel Hackmann and Sierra Boggess (Carrie) make welcome reappearances. Both are first class; not only do they sing very well and authentically but both of them make their characters come to life. Mind you, that’s true of all the other principals. Mikaela Bennett is genuinely touching as Julie Jordan; I really enjoyed her performance. Francesca Chiejina (Nettie) has a more opulent voice than her colleagues but her sound works beautifully in this context, not least because it differentiates Nettie from the rest of the cast. I enjoyed Julian Ovenden’s richly characterised portrayal of the rather strait-laced Enoch Snow while David Seadon-Young shows us just what an unscrupulous, conniving piece of work Jigger is.

The chorus is given the title of the Carousel Ensemble. There are twenty-two singers and they sing with punch and gusto; they’re ideal. John Wilson’s Sinfonia of London do the orchestral honours. They relish the score, playing with pizzazz and incisiveness in the many passages which require such treatment but also displaying a great deal of finesse in the more sensitive passages – of which there are a lot, especially underneath the dialogue. Incidentally, one should pay tribute to Don Walker (1907-1989) who orchestrated the score for Rodgers and Hammerstein. He did a fantastic job; the scoring is consistently colourful and inventive and the Chandos recording allows us to enjoy his work to the full.

John Wilson has given us many excellent recordings of concert music by a very wide range of composers, including Eric Coates, Kenneth Fuchs, Rachmaninov, Ravel and Respighi to name but a few. However, I feel that his true métier is music such as we hear on this album. His conducting is stylish and full of vitality; above all, he seems completely in tune with the spirit of the score.

The recording was made in the same venue as the recording of Oklahoma! The Susie Sainsbury Theatre at the Royal Academy of Music seems to be an ideal venue for such a venture. The SACD sound – I listened to the stereo layer – is clear, crisp and presents the music ideally. As I’ve indicated, the documentation – the essay and synopsis by David Benedict and the full libretto – is first class.

Overall, this first complete recording of Carousel is a terrific listening experience; Wilson and his colleagues do full justice to this Broadway masterpiece.

But, after giving all the justified plaudits to the musicians and the engineers the real heroes of this enterprise are, of course, Rodgers and Hammerstein. Oscar Hammerstein’s lyrics are witty and so inventive – it takes some doing to conjure up entertaining lyrics on the subject of meals and ingredients (‘This was a real nice clambake’). Importantly, though, there’s genuine emotional depth in the lyrics of many of the numbers, Billy’s Soliloquy, ‘You’ll never walk alone’ and ‘If I loved you’ being the prime examples. Rodgers’ music is inventive, original and ear-catching. Like his partner, he writes with real emotional depth. Between them, they conjured up a truly great show. No wonder the fifteen-year-old Stephen Sondheim, who was present at the New Haven premiere, was moved – and, clearly, influenced by Carousel when he came to write his own shows.

The booklet contains a number of session photos in which, almost without exception, the musicians are smiling. It would seem that they had, in Hammerstein’s words, ‘a real good time’ making this recording. If you buy these discs, I think you will have just as good a time.

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free