Déjà Review: this review was first published in September 2007 and the recording is still available.

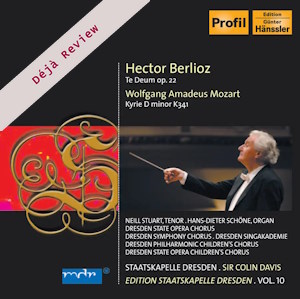

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869)

Te Deum, Op 22 (1847-49)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Kyrie in D minor, K341 (?1780/81)

Neill Stuart (tenor), Hans-Dieter Schöne (organ)

Dresden State Opera Chorus, Dresden Symphony Chorus, Dresden Singakademie, Dresden Philharmonic Children’s Chorus, Dresden State Opera Children’s Chorus

Staatskapelle Dresden/Sir Colin Davis

rec. 1998, Kreuzkirche, Dresden, Germany

Profil PH06039 [60]

It seems quite incredible that Sir Colin Davis will celebrate his eightieth birthday on 25 September. It’s timely, therefore, that this CD should be issued now as it lets us hear him conduct music by two composers with which he’s been very closely associated during his highly distinguished career. Fittingly, the performances on the CD also marked another important anniversary because they were given as part of the second programme of the 450th anniversary season of the Staatskapelle Dresden and this disc contains live performances recorded then.

Sir Colin has had a long association with the music of Mozart and he’s been a great servant and interpreter of the music of several other composers, among which we may number Tippett, Elgar and Sibelius. But for all his distinction in other composers’ music the one name with which he’s become pretty much synonymous is that of Berlioz. I’m far from blind to the excellence of several other conductors in Berlioz – Gardiner, Monteux and Munch to name but three – but I think Davis stands apart from all others not just on account of the consistent excellence of his Berlioz performances but also on account of the sheer range of the works he’s taken on. I can’t think off hand of a single major work by Berlioz that he hasn’t performed frequently, with the possible exception of the early Messe Solenelle, and he’s recorded just about every work of significance, in most cases more than once. Such dedication to a composer is remarkable.

During his tenure at the helm of the London Symphony Orchestra Sir Colin’s concert performances of most of the major Berlioz pieces were issued on CD on the LSO Live label. A couple of works – the Te Deum and the Grande Messe des Morts – seem to have slipped through the LSO Live net, though one lives in hope. Therefore, this fairly recent live recording of the Te Deum was one that I was particularly keen to hear, especially as I don’t have on CD Sir Colin’s 1969 recording for Philips with the LSO, the recording through which, on LP, I first came to know the work.

The Te Deum, which the composer himself referred to as the “little brother” of the Grande Messe des Morts (see review of the concurrently released Davis recording of this on Profil PH07014), is firmly in the unique French tradition of grand public pieces on a monumental scale. It’s an inspiring work but to do it justice requires substantial forces and a comparably large performance space, which is what happens here. Thus concert performances of it are relatively rare and, in fact, I’ve only ever attended one as a member of the audience, though singing in two performances of it as part of a large combined Anglo-French choir in 1998 was an experience I shall never forget. By it’s very nature it’s also difficult to “compress” into a recording and then reproduce satisfactorily under domestic listening conditions although, in fact, there have been a few successful recordings over the years.

Even if I’d had available to me the CD version of Davis’s first recording of the work I’m not entirely sure I’d have used it for comparisons since it was made under studio conditions. For that same reason on this occasion I didn’t refer to Sir Thomas Beecham’s fine 1953/4 recording. Instead I made some comparisons with two other recordings that derive form concert performances: Claudio Abbado’s 1982 reading for DG and a Delos version from 1996 on which Dennis Keene conducted the Voices of Ascension

The monumental aspect of the score is apparent from the very start, where Berlioz achieves a great coup through the simple device of huge alternating chords first on the organ and then from the orchestra. Berlioz famously likened the effect to “Pope [the organ] and Emperor [the orchestra]”. These massive chords make their full effect here though the DG recording – in the slightly smaller acoustic of St. Alban’s Abbey – is also very powerful and the organ tone is a little brighter, while the huge beast that is the organ of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York, the venue for the Delos performance, makes a stunning sound. The first movement, ‘Te Deum laudamus’, is a paean of praise and we may wonder how much Berlioz expected the separate lines in his two three-part choirs to be heard clearly or if, in fact, he sought more of a tumultuous effect. Be that as it may, Sir Colin and the engineers between them ensure that a considerable amount of detail can be heard – with one rather important exception.

In the first and last movements Berlioz included a separate unison line for a third choir of treble voices, ideally comprised of children. These have a crucial role to play but I’m afraid that on this new recording it’s not easy to hear them – nor is the line especially distinct on the Delos recording. In the DG version the children’s choir cuts through the texture like a knife. It’s an absolutely thrilling sound and I’m sure it’s just what Berlioz would have wanted. An important score in Abbado’s favour. Otherwise, Sir Colin controls the vast first movement very impressively indeed. There’s power and momentum and a great sense of occasion in his reading.

Although the Big Moments in the Te Deum are hugely exciting I find some of the quieter moments even more original and impressive, in the same way that I think the Offertorium movement, ‘Domine Jesu Christe’, is in many ways the most original section of the Grande Messe des Morts. So the movement in the Te Deum which I most admire is the second one, ‘Tibi omnes’. Here the quiet chords on the word ‘Sanctus’ [track 2, from 2:02 in this recording], against which the wind chatter, are most atmospheric and Berlioz builds this material, each time it comes, to a huge and impressive climax. Sir Colin brings these passages off splendidly and he realises perfectly the marvellous quirks in Berlioz’s orchestration such as the gentle strokes on bass drum and cymbal and “hairpin” notes on the trombones that colour the second singing of ‘Sanctus’.

I thought the performance of the third movement, ‘Dignare’ was just a little less successful. It seems from the booklet photograph taken during the performance that the Kreuzkirche, where these concerts were given, is a huge building and I imagine that it must have been a challenge to co-ordinate the ensemble. I suspect that lies behind the occasional slight imprecisions of ensemble that I detected in this movement. It’s the most difficult music that the choir has to sing but there were some occasions in the first few pages when I thought that the sopranos and tenors of Choir I were marginally out of synch with each other and with the orchestra. Another very slight imperfection comes with the choir’s attack on the very first chord of the fourth movement, ‘Christe rex gloriae’, which some singers anticipate by a whisker. It’s only a small thing in itself but it’s the sort of thing that might become wearisome with repeated listening – and such slight slips are absent from the Abbado and Keene versions, both of which are also live. However, I must say immediately that this is the only blemish – and a tiny one at that – on Davis’s account of the fourth movement. Overall it’s magnificent, achieving a blazing climax at cue M in the vocal score [track 4, 4:12].

The fifth movement, ‘Te ergo quaesumus’, introduces the tenor soloist in a role that’s not dissimilar to the tenor solo in the Grande Messe des Morts, not least in the often cruel demands made on the singer. Neill Stuart has a firm, ringing tone and I admired the clarity of his diction and the accuracy of his pitching – every note is hit bang in the middle. Unfortunately, his singing is pretty one dimensional in the sense that there seems to be little attempt at dynamic variety and contrast. I think that, in fairness, two points should be made. Firstly he’s clearly working hard to project into a very large acoustic. Secondly I don’t think the engineers have done him any favours for I strongly suspect the microphone was placed too close to him; a little bit of distance might have worked wonders. For Abbado, Francisco Araiza, also singing live in a big church it must be remembered, gives an object lesson in how this solo should be delivered. He too has the necessary heroic ring but he shades the music beautifully and imparts a good amount of sensitivity to the dynamics. Furthermore, it doesn’t sound as if he’s singing straight into the microphone. John Aler, on Delos, is somewhere between the two. The movement ends with a rapt unaccompanied choral passage, which is marked ppp in the score. Sir Colin’s singers, though very good, don’t quite achieve this. Keene’s wholly professional choir are superb here and Abbado’s chorus runs them close.

The final movement, ‘Judex crederis’ is like an implacable juggernaut. Sir Colin keeps the music moving very well, achieving the grandeur – and, in one or two places, the menace – without sacrificing rhythmic precision and drive. His male singers are impressively strong at ‘Per singulos dies’ [track 6, 3:38] and the whole movement is superbly brought off. One very small point is that there’s a crucial part for side drum (s) as this movement rolls on its way. The Dresden drums are conventional side drums. On the Abbado and Keene recordings either the snares are relaxed or tenor drums are used. However the effect is achieved one gets the feel of a dull military tattoo and I find that adds an extra frisson to the texture.

One or two slight reservations aside, Sir Colin’s performance of the Te Deum is a hugely impressive account of a great pièce d’occasion. It’s one that I shall be very glad to add to my shelves as a more or less up to date representation of our greatest Berlioz exponent in this superb score. Pressed to choose amongst those versions under consideration, however, I’d say that on balance the Abbado version still represents the best choice. It’s tighter overall than either of its rivals and Abbado has the very significant advantage of the best tenor soloist and the most telling children’s chorus.

The Profil disc contains a filler in the shape of Mozart’s D Minor Kyrie. I assume that the full adult choral forces took part (the booklet notes tell us that there were some four hundred performers involved in the Berlioz.) It’s certainly a big scale Mozart performance and Sir Colin does very well to keep the performance on the move. I gather that in the concert itself the Mozart preceded the Berlioz and I think that ordering might have been preferable on disc as well.

The recorded sound derives from a radio tape made by Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk and it’s of very good quality indeed. It must have been a significant challenge to the engineers to capture the vast ensemble employed in the Berlioz but they’ve made a most convincing job of it. The booklet notes, in German and with an English translation, are serviceable but no texts or translations of either work are provided.

John Quinn

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free