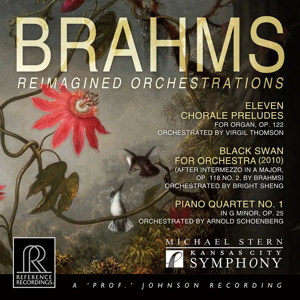

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Reimagined Orchestrations

Eleven Chorale Preludes, Op 133 (1896; orch. Thomson 1957)

Intermezzo, Op 118 No 2 “Black Swan” (1893; orch. Sheng 2007)

Piano Quartet No 1, Op 25 (1861; orch. Schoenberg 1937)

Kansas City Symphony/Michael Stern

rec. 2019, Helzberg Hall, Kauffman Center for Performing Arts, Kansas City, USA

Reference Recordings RR-152 [79]

This album not only explores the lasting significance of the composer Lionel Barrymore called “the genius with the whiskers”, but also the multifaceted ways in which posterity has interpreted his legacy.

For Virgil Thomson, whose Gallic orchestration of the late Eleven Chorale Preludes opens this disc, Brahms was the Apollonian defender of classical proportion and restraint – or neoclassical, I should say. Listen to how he propels “Herzlich tut mich erfreun” merrily along with pizzicato strings, accented by glockenspiel; or “Schmücke dich, O liebe Seele”, scored for woodwinds led by muted trumpet. Stravinsky’s music, especially that of the Canticum Sacrum and “Vom Himmel hoch” Variations, is never far away. The latter, composed about a year before Thomson began his orchestration, is a likely model here. Wielding his instrumental colors with far more delicacy than Brahms was ever capable of, Thomson fashions the German composer into a Boulangerist avant la lettre, anticipating her school’s retour à l’ordre priorities.

On the other side, geographically and aesthetically, was Arnold Schoenberg, whose declaration that he “credit[ed] [himself] with having written truly new music, which being based on tradition, is destined to become tradition” staked his claim as inheritor of Brahms’ legacy.

Schoenberg makes that emphatically clear in his orchestration of the Piano Quartet No. 1, whose possessiveness contradicts his outwardly modest statement that he went no further than Brahms himself would have done – had he been alive at the time this orchestration was made, that is. That dangling proviso opens up the use of instrumental colors that would have left Brahms’ head spinning, including divided strings, stopped horns, and topped in the finale by a giddy xylophone. A decade later, Schoenberg, in his essay “Brahms the Progressive”, lauded the elder composer for having inaugurated “progress in the direction towards an unrestricted musical language”. This orchestration not only manifests that belief in sound, but by its very eclectic colors looks forward to a world neither Brahms nor Schoenberg would ever know, wherein composers were freed of dogmas and allowed to roam wherever they please.

Bright Sheng’s orchestration of the Intermezzo in A major, Op. 118, no. 2, renamed Black Swan here, is the program’s pivot; it resulted from a commission for Gerard Schwarz’s farewell season as music director with the Seattle Symphony. Placed between this program’s two big works, Sheng’s rendering makes a tellingly contrasting statement of postmodern regret. Whereas Thomson and Schoenberg each attempted to claim Brahms for themselves and on behalf of a future they were actively defining, Sheng is altogether different. His gravely beautiful orchestration, with touching use of brass and harp, seems to look longingly at Brahms’ music as a kind of Eden, from which posterity was cast out and fated never to return. We can view Brahms with appreciation and affection, Sheng suggests, but we must ultimately concede that the passing of time has made him too distant, too estranged from us.

This is the latest in a series of interpretively engaging and sonically outstanding discs by the Kansas City Symphony for Reference Recordings. Conducted by its longtime music director, Michael Stern, the works on this program offer much opportunity for the orchestra to show off its formidable flexibility, beauty, and power, not to mention the quality of its section leaders. Brahms: Reimagined Orchestrations is a fitting valedictory to a twenty-year partnership, which ended last season, that has led to the rise of an orchestra that can now boast of being among the finest in the United States.

Néstor Castiglione

Previous review: Jim Westhead (August 2024)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free