Déjà Review: this review was first published in September 2005 and the recording is still available.

Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915)

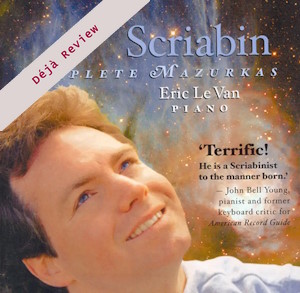

The Complete Mazurkas

Ten Mazurkas, Op. 3 (1888-1890)

Nine Mazurkas, Op. 25 (1898-1899)

Two Mazurkas, Op. 40 (1903)

Eric Le Van (piano)

rec. 2002, Studio 2, Bayerischer Rundfunk, Munich, Germany

Music & Arts CD1125 [73]

This is an exceptional recording of Scriabin’s 21 Mazurkas. In the booklet notes, the Scriabin scholar John Bell Young is quoted as saying of Le Van, “Terrific! He is a Scriabinist to the manner born”. After listening to the Music & Arts recording, I certainly agree with Mr. Young and have greatly enjoyed these illuminating interpretations.

I should relate that John Bell Young and I have corresponded in the past, and I have learnt a great deal about Scriabin through Young’s expert counsel, speeches and articles. Young talks about being a Scriabinist. Just what is a Scriabinist, and can a pianist well convey the music without being one?

In the interests of time, I’ll only offer short and simple answers. A Scriabinist has tapped into the psychology of the composer and his music through study and the performing/listening process. As an example, study tells us that Scriabin was highly critical of how other pianists played his music. He complained that most pianists did not offer the rhythmic elasticity his music required and also played in too heavy a manner. He insisted that his works needed frequently changing fluctuations in tempo and dynamics to reflect his numerous changes in emotional content. We also know that Scriabin performed his own music in the same manner in which he talked about it, because there are recorded documents of his interpretations such as on the Russian Season disc noted in the heading.

The above might appear to bring up the issue of whether Scriabin was the best judge of how to interpret and convey his compositions. Personally, I don’t think this is an issue at all. If you want to hear the ‘real Scriabin’ through other artists, those artists will have to play in the Scriabinist style and reflect his sound-world. You might personally enjoy an alternative type of interpretation, but you will only be listening to Scriabin’s notes. We can’t be sure how Bach wanted his works to be performed, but we are on solid ground with Scriabin.

What is the Scriabin sound-world? Perhaps the most crucial element to keep in mind is musical tension. I am not referring to an overt display of tension, but a subtle display that is founded on articulation, inflection and brooding bass lines. Playing the music with insufficient tension is the “kiss of death” for a performance of Scriabin’s music.

Cross-rhythms are another major part of Scriabin’s sound-world, creating much of the beauty and interest in the music. Melancholy is also a strong component, and you won’t find a composer who conveys it more effectively or frequently; in excellent performances, the sadness pierces the heart at every turn. Suspended notes, naive and unfettered joy, playfulness and rhythmic elasticity of both the horizontal and vertical variety are important ingredients as well.

Then we have all those emotional outbursts so characteristic of Scriabin’s compositions. Where do they musically come from? – the tension, melancholy, and cross-rhythms. If the pianist does not convey these qualities, the outbursts have no meaning and sound entirely self-indulgent.

Lastly, there is the matter of spacing between notes. Scriabin did not take kindly to his music being played with empty spaces. He used spacing to carry-over the previous thought and act as a conduit for the next idea. This is where extremely slow performances of Scriabin’s works run the risk of cluttering the musical landscape with empty space, a trait that ruins the Scriabin series of piano works played by Gordon Fergus-Thompson on ASV. Does Scriabin’s music sound best when the above features are covered? Most assuredly. To ignore them makes his music entirely generic in the worst sense of the ‘international style’.

I have been hitting the byways of this review and should turn my attention to Eric Le Van’s background. He was born in Los Angeles and started playing the piano at the age of five and the violin when he was seven. One of his teachers was Earle Voorhies who studied with the Liszt pupil Alexander Siloti. Eventually, Le Van received a Fulbright grant to study with Professor Karl-Heinz Kammerling in Hanover. Le Van already has a few recordings under his belt, including highly acclaimed discs of the solo piano music of Brahms and Raff. He currently resides in France, performs often in public, and is the Artistic Director of the International Franz Liszt Festival.

To give a clear idea of how Le Van treats the Scriabin Mazurkas, introducing the recorded performances of Michael Ponti and Artur Pizarro is just the ticket. Although both pianists are excellent, their approaches are worlds apart. Ponti is quick and light on his feet with exuberant rhythmic patterns and exceptional vertical elasticity. Pizarro is quite slow and rich with outstanding articulation and freely flowing rhythms. Ponti places high priority on clarity and the detail of inner voices, while Pizarro follows the long line of the music.

If we think of Ponti and Pizarro as occupying opposite ends of the musical spectrum, Le Van is positioned right in the middle. His clarity and detail are exemplary, although less well-defined than Ponti’s. Le Van’s tempos are moderate as well as his rhythmic bounce and vertical/horizontal elasticity. Essentially, a look at any of his musical features shows his approach to be one of moderation.

Of course, a moderate approach does not reveal how effectively the artist portrays Scriabin’s sound-world. The following is my assessment of how well Le Van handles some of the basic Scriabin parameters:

Tension – Le Van’s application is superb in each of the 21 Mazurkas. This makes for very compelling interpretations, the consistent urgency of his readings rendering the emotional outbursts as natural and inevitable releases of energy.

Rhythmic Elasticity – Although different listeners would have a range of opinions concerning many of Le Van’s interpretative stances, I can’t imagine anyone not agreeing that his elasticity is very fluid with a great sense of the composer’s long musical lines and structural coherence. Le Van’s horizontal elasticity is particularly stunning, although the vertical lines certainly stream upward in enticing fashion.

Heaviness – As mentioned earlier in the review, Scriabin often complained that pianists used too heavy a touch in their performances. He definitely would not complain about Le Van’s touch which is feathery and delicious. For a good example, check out the first section of Op. 3 no. 4 where the melody line glides effortlessly over the foundation created by the lower voices.

Fluctuations in Tempo and Dynamics – Not as strong in this area as Ponti, Le Van nevertheless displays a fine degree of adaptation and well handles the sudden nature of Scriabin’s ever-changing musical environment.

Melancholy – Le Van carries Scriabin’s pervasive melancholy with incisiveness and beauty. Pieces such as Op. 3/3 and 3/5 are heart-stoppers in his hands, and I think it fair to say that no other recording of the Mazurkas captures the musical sadness as thoroughly.

Add in a superb soundstage of clarity, depth, and richness, and we have one of the most successful Scriabin piano recordings in the past few years. It is not an easy task to be competitive with the greatest Scriabin pianists of the past such as Vladimir Sofronitsky, Samuel Feinberg, Sviatoslav Richter, Roberto Szidon, Vladimir Horowitz, and Scriabin himself. Le Van deserves to be placed in this exalted company, and he enjoys the best sonics that modern recording techniques can offer.

In conclusion, Scriabin’s piano music gets only a fraction of the exposure it warrants, and I personally place the blame on the generic style used by most pianists of the modern era. Many listeners have formed their opinion of Scriabin from the Piers Lane recordings on Hyperion and the lifeless Fergus-Thompson interpretations mentioned earlier in the review. These recordings do not give us a true and compelling picture of Scriabin’s sound-world, but Eric Le Van offers a full-course dinner of the composer’s musical personality. He is inside Scriabin’s complex and self-oriented psychology, and that’s 90% of the battle. Grab up this Music & Arts release and enjoy Scriabin’s unique and transcendent music performed by a “Scriabinist to the manner born”.

Don Satz

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free