Déjà Review: this review was first published in September 2002 and the video is still available.

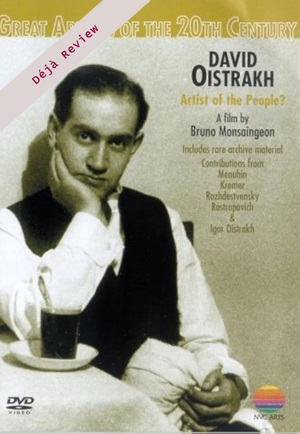

David Oistrakh: Artist of the People?

A film by Bruno Monsaingeon made in 1995

NVC Arts DVD 3984-230302 [75]

David Oistrakh died in 1974, and one of the more frustrating regrets of my life was not hearing him play live. Frustrating on two counts: first, I had the chance, and second, he was, on this occasion, playing in concert with Sviatoslav Richter.

I was at boarding school and a violin playing teacher had managed to get tickets for a rare recital by the two great Soviet artists at the Royal Festival Hall. It must have been a Saturday because I was running in an athletic competition at another school. I’d agreed to rendezvous back at my school in time for us to catch a train to Waterloo station for the concert. The team bus didn’t arrive. By the time I did get back, the teacher, my ticket and the opportunity of a lifetime had gone.

At the time, Oistrakh, who was already over 50, had only recently been discovered by the West. I knew about him because the first LP I ever owned (and the only one for a while) was of him playing the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto. In my youthful conceit, whenever the subject of violinists or violin music came up, I would take the opportunity of saying, “… but have you heard Oistrakh?”.

Later, when I went to College, an era when students conformed by plastering their walls with posters of Che Guevara and the Beatles, I had a violin playing friend who only had one thing on his wall. It was a picture of Oistrakh in full flow at what I assumed to be a rehearsal. He was in shirtsleeves with braces holding up trousers, the waist band of which was hoisted above a substantial paunch. The violin was thrust into a double chin and jowls dangled at either side of a sweat drenched face. Not a pretty sight, you may say. My friend and I thought it majestic.

This film, made in 1995 by Bruno Monsaingeon, himself a violinist, is released on DVD/Video for the first time. I had not seen it before and found it absolutely riveting (but then I do have a special interest as implied above). The format is the standard one of distinguished people reminiscing, interspersed with musical and newsreel clips, together with some voice-over quotes from what are presumably Oistrakh’s diaries and letters. Most of the clips come into the category of what is usually termed “rare footage”. Ferreting out material for the film, Monsaingeon says, took him over 15 years.

All is edited together with great skill, following Oistrakh’s life chronologically grouped into ten cued chapters from cradle to grave. The cast list of anecdoters is wisely kept short, chosen for both their own distinction and articulate skill in reminiscing. There is Menuhin the friend, Rostropovich and Rozhdestvensky the Soviet colleagues, Gidon Kremer the pupil and Igor the son. No mean violinist himself, Igor clearly remained posthumously in awe of his father, while Kremer is the only one who displays a sense of unease in his relationship with his master. He tactfully gives an impression of feeling stifled by Oistrakh’s teaching methods, which were of the “this is how you do it” school. We can see this from clips in chapters devoted to Oistrakh “as teacher” and as “conductor”. Rehearsing a Mozart violin concerto as conductor, Oistrakh runs the session as if it were a master class, showing the strings what to do with violin in hand. However, all is done with a disarming, self-effacing smile. Nevertheless, he was regarded as a great teacher and was for most of his life on the staff of the Moscow Conservatory with, in a wonderfully incestuous arrangement from 1958, Igor as his assistant.

All the others, however, depict a much loved man, none more so than Menuhin, who developed a very close relationship with Oistrakh on the occasions they were able to meet. Menuhin offers as explanation of their bonding the fact of shared Russian/Jewish roots. Anecdotes of Soviet repression and bureaucracy abound and Menuhin tends to cast himself as saintly hero and at one point (in a story about getting an exit visa for an out of favour, grounded Rostropovich to leave the USSR for a concert) as a victorious David against the world’s totalitarian Goliath, contacting Brezhnev direct and threatening him. “He got his visa the next day. There’s only one way to treat bullies…”, says the giant slayer. Great anecdotal stuff, this. It is Menuhin though who comes up with some of the most generous remarks about Oistrakh in the whole film, “I am sure I would have loved at some stage of my life to have studied with him”, and, “he was a darling”.

Of course a running theme throughout the film is that of the horrors of Soviet repression and how that forced sincere and upright personalities to compromise their integrity. Oistrakh had witnessed first hand, when living with his family in an apartment before the war, the 4 a.m. knock on the door and the subsequent disappearance of neighbours, fearing the knock himself. Rostropovich tells a story in the film of how Oistrakh used this experience as an explanation. He took the cellist aside one day to admit that he had signed an attack on his friend that would appear in Pravda the next day. “I can only plead with you to understand, and have the courage to forgive me”. This is where the anecdotal stuff becomes unbearable. Yet somehow, Rostropovich and Rozhdestvensky, who both have a superb sense of imagery, manage to try to look on the bright side. “Music was all we had left … a kind of opening, a window to the sun, to fresh air, to life”, says Rostropovich. And Rozhdestvensky: “You can compare us to a vine. If the vine grows in a thankless, chalky, stony soil, the wine is better. How much it costs is another question”.

Oistrakh was forced to play a game and dance as a puppet to the tune of the Soviet régime. But as Rozhdestvensky, who comes over as a world-weary philosopher who’s been through it all himself, pragmatically points out, “If he had not kept his mouth shut we would not have heard his violin”, and, “He never really believed in totalitarianism otherwise he couldn’t have played the way he did”.

And hear him play we do. Twenty-five different pieces are heard in all too short extracts. People will have their favourites. Although transfixed by them all, clips from a 1965 Moscow performance of the Brahms Double Concerto with Rostropovich particularly moved me by its unique Russian intensity and the sense of committed teamwork. Rostropovich’s eyes glued on Oistrakh, his forgiven betrayer, with occasional glances at the conductor. Then there is the hair-raising performance of the cadenza from Shostakovich’s Second Violin Concerto (a present to Oistrakh from the composer for his 60th birthday) filmed at its world premiere. We are then treated to a recording of a phone conversation between the two. Oistrakh apologises for struggling at one point because the music was so fast. No, no, says Shostakovich, I only heard a great performance. And then, in a rare manifestation of Shostakovichian dry wit, “I couldn’t have played it better myself “.

Monsaingeon has done a magnificent job in unearthing and editing the musical extracts and we get a good overview of Oistrakh’s style – that of combining breathtaking virtuosity with a selfless non-showy dedication to the music and deep, insightful intensity. However, music lovers are bound to be frustrated at not being able to hear a whole movement or even a complete work. In this age of DVD, one could reasonably expect some of these to be available as appendices. As compensation, it would have been handy to be able to return to choice extracts, but although there is a list of these in the booklet, they are not cued. All we get out of the DVD technology is the chance to choose a subtitle language. This, in my opinion, is not good enough.

However, this is a moving film about a very great musician and it also serves as an important document in the context of the history of 20th century music.

John Leeman

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site

Available as a download or streaming at: vimeo ~ medici.tv ~ mezzo.tv