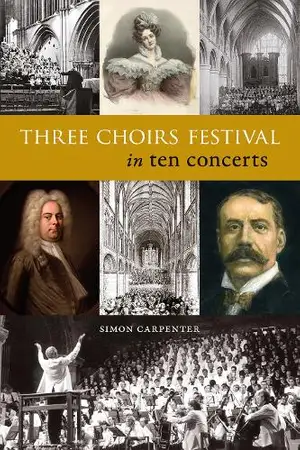

Three Choirs Festival in Ten Concerts

By Simon Carpenter

First published 2024

162 pages, including appendices and index

With colour and black & white illustrations

Paperback

ISBN: 978-1-9108-3975-1

Logaston Press

There is already a detailed history of the Three Choirs Festival, compiled by Antony Boden and Paul Hedley (review). It might be wondered, therefore, if there is room in the market for a second history of the Festival. I think the answer to that is yes, because Simon Carpenter has taken a different approach. The history which Boden and Hedley wrote was comprehensive and chronological. Carpenter, by contrast, has chosen to tell the story of the world’s oldest music festival through the prism of ten concerts which he has identified as being among the most significant in the Festival’s long history. His scheme is to discuss the concert in question and then to use that event as a ‘peg’ for outlining more of the Three Choirs history. It’s an approach that works well.

Carpenter is well qualified to undertake this task. For one thing, his musical roots go deep; he was a chorister at Guildford Cathedral under Dr Barry Rose. Since moving to Gloucestershire, he has sung in amateur choirs and he has combined his twin enthusiasms for history and music by acting as volunteer archivist and historian of the Three Choirs Festival.

By way of background, I think it’s a fairly safe bet to say that the Three Choirs Festival is the oldest music festival in the world. It’s generally accepted that the first Meeting of the three cathedral choirs of Gloucester, Hereford and Worcester took place in Gloucester in 1715. Since then, the gatherings have taken place annually, though a few have been lost to national emergencies: the festivals were suspended during the two World Wars and 13 festivals were lost; more recently, the 2020 Festival fell victim to Covid restrictions. The original purpose of the choral Meetings was to raise funds for the support of widows and orphans of clergy in the three dioceses. The three choirs combined in order to sing services but gradually the scope widened, concerts were put on and the gatherings lasted for three days and eventually were extended further into the now long-established one-week format.

Simon Carpenter’s first selected concert is the Three Choirs premiere of Messiah in 1757; this took place in the city of Gloucester. Interestingly, the oratorio was given not in the cathedral, as one might have expected, but in a large nearby hall, the Boothall, which was not demolished until 1957. In 1757, Handel’s oratorio was deemed to be a secular work; only liturgical music sung by the cathedral choirs during services could be performed in the cathedral. Messiah immediately became an annual fixture at Three Choirs; it was performed, in whole or in part, at every festival until the 1950s. It was later joined as an immovable object in the programme planning by Mendelssohn’s Elijah, first performed at a Festival in 1847. Carpenter offers a succinct, lively narrative of the inaugural Messiah performances and what it led to; he gives us a good flavour of how different were those early festivals by comparison with what gradually became the norm. Incidentally, performances of Messiah and other such works were allowed in Hereford Cathedral from 1759; Worcester and Gloucester adopted the same procedure within a few years.

Carpenter devotes a chapter to the relationship between the Three Choirs Festival (especially those held in Gloucester) and Sir Hubert Parry, whose family had a magnificent country house just outside Gloucester. The first Parry piece heard at a Festival was a short orchestral work, Intermezzo Religioso, which was performed at the 1868 Gloucester Festival. Carpenter tells us that the piece, which was one part of the excessively long programmes so readily inflicted on nineteenth century audiences everywhere, met with a “muted response”. Notwithstanding that, further Parry pieces were featured in later programmes, starting with Prometheus Unbound at the 1880 Gloucester festival. I’m afraid I can’t quite agree with Simon Carpenter’s implication that this work can be ranked among the composer’s “finest works”; when I eventually got to hear it in 2023, through its premiere recording, it struck me as distinctly uneven, especially in terms of the choral writing (review). After Prometheus Unbound another 13 works by Parry were premiered at Three Choirs between 1881 and 1912; as Carpenter remarks, “Clearly, the Festival couldn’t get enough of him, or he the Festival. Or he just couldn’t say no”.

Arguably, a much more significant relationship was the one between Three Choirs and Sir Edward Elgar. Carpenter uses the first performance of the overture Froissart, conducted by the composer during the 1890 Worcester Festival, as the spur for his discussion of this relationship. Froissart was a success but it did not immediately open the flood gates for Elgar’s music at Three Choirs, despite the burgeoning reputation of the Worcester-born composer. Carpenter makes a very interesting point (which was news to me) when he says that a prime factor was that Three Choirs commissions were honorary, whereas festivals such as those in Leeds and Birmingham offered fees. Since Elgar was impecunious in those days, I suppose it’s unsurprising that he should have given his bank balance priority over local loyalty. However, as the years went by Elgar’s music, and The Dream of Gerontius in particular, became part of the Three Choirs staple diet and he frequently conducted his own works.

Four other notable English composers each have a chapter: Ralph Vaughan Williams, Herbert Howells, Gustav Holst, and Gerald Finzi. Unsurprisingly, Carpenter uses the 1910 first performance of Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis as the basis for his discussion of VW’s long involvement with the Festival. The Fantasia was cooly received by the press; the well-chosen extracts that Carpenter reproduces from contemporary reviews range in tone from incomprehension to hostility. As I read the various quotations, I realised that they offer a salutary reminder to all critics of how perilous an undertaking it can be to pass judgement on new music on the basis of the first performance. I expected that the chapter on Howells would focus on the belated premiere of his masterpiece Hymnus Paradisi at the 1950 Three Choirs in Gloucester. However, Carpenter takes a different path; he selects instead the 1922 premiere of a much less familiar work, Sine nomine for (wordless) soloists and chorus with orchestra. It’s a work that I’ve only once heard in concert – when it was revived at the 1992 Festival – but Carpenter was right to select Sine nomine,not least because it demonstrates the willingness of Three Choirs, even then, to afford a shop window to composers of the younger generation. Significantly, it was Elgar who was instrumental in the Festival’s decision to offer major commissions that year not only to Howells but also to Arthur Bliss (A Colour Symphony) and Eugene Goossens.

Holst’s connection with the Three Choirs Festival was not quite so deep – nor so long lasting – as that of his great friend, Vaughan Williams. In that regard, perhaps it’s significant that the performance selected by Simon Carpenter is that of a very short work which is little-known even today. The motet The Evening Watch for unaccompanied choir and two soloists was premiered at the 1925 Festival; I’m not sure that it has been revived all that often at subsequent Three Choirs Festivals. By contrast, Carpenter reminds us of a number of Three Choirs performances of the visionary Hymn of Jesus in the 1920s and 1930s, three of which were conducted by the composer. The chapter on Finzi takes as its starting point the lovely Clarinet Concerto which was unveiled, under the composer’s direction, at the 1949 Three Choirs Festival. Carpenter then describes in excellent detail Finzi’s connection with Three Choirs, going back to the early 1920s and including the composer’s close friendship with Herbert Sumsion (1899-1995), who was Organist of Gloucester Cathedral from 1928 to 1967. In the past, I have read two detailed biographies of Finzi but seeing everything related to Three Choirs gathered together in a concentrated form, as here, brought home to me more fully just how deep was Finzi’s affection for and involvement in the Festival over the years.

Carpenter has an interesting chapter on women composers at the Festival. It came as a bit of a welcome surprise to learn that in the nineteenth century two female composers managed to make some headway, albeit limited, at Three Choirs. The names of two of the three women referenced in this book will probably be as unfamiliar to other readers as they were to me. Alice Mary Smith (1839-1884) was clearly a prolific composer; she has the distinction that in 1882 her Ode to the passions, for soloists, chorus and orchestra was the first work by a female composer to feature in a Three Choirs programme. At the same (Hereford) festival, Rosalind Ellicott (1857-1924) sang a song which she had composed. Then, in 1886, her Dramatic Overture for orchestra was introduced to the Gloucester audience. The third female composer discussed by Carpenter is rather better-known; the redoubtable Dame Ethel Smyth. Not only was her music heard at Festivals in the 1920s, but she also became the first female conductor to grace the Three Choirs podium, in 1925 and again in 1928.

One event merits a dedicated chapter: the first occasion on which a Three Choirs performance was greeted with applause. To me – and I’m sure to most other people – it seems distinctly odd that performances of such works as The Dream of Gerontius, Elijah and Messiah, to say nothing of the premieres of Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis and Hymnus Paradisi could be followed by stoney silence, but such was the case until the late 1960s. Simon Carpenter provides some illuminating detail concerning how the applause ‘taboo’ was finally broken. It nearly happened after a 1965 performance of Belshazzar’s Feast when a few brave souls accorded the performance a smattering of applause; but the dam finally burst at the 1969 Festival when the audience showed its appreciation of the various items in a concert by the National Youth Orchestra. Carpenter is surely right to point out that the audience was not a typical Three Choirs assembly but, rather, contained a lot of family and friends of the NYO. Good for them, we may say. Audiences were inconsistent in the matter of applause at further concerts during that week in 1969 – and Sir Adrian Boult specifically requested that there be no applause at the concert which he conducted – but a line had been crossed; for the future, audience appreciation became the order of the day.

The end of the applause taboo gives Simon Carpenter the springboard to give an overview of how the Three Choirs Festival has continued to evolve and develop since 1969. He includes in this sectionsome reflections by Gloucester Cathedral’s Director of Music, Adrian Partington (whose connections with Three Choirs, albeit not unbroken, go back to 1969) and from Alexis Paterson, who stepped down as the Three Choirs Festival CEO in 2024. However, I think this concluding section is slightly disappointing, not least because it’s rather condensed. I wish the book had outlined in a bit more detail the way in which the Three Choirs Festival has embraced music of our own and recent times, not least through commissions. Not all the new works played at recent Festivals have been uniformly successful – Malcolm Williamson’s Mass of Christ the King (1977-78) seems to have sunk without trace, for example. But in the last twenty years or so notable scores by the likes of John Adams, Eleanor Alberga, Jonathan Dove, Gabriel Jackson, John Joubert, James MacMillan, Colin Matthews, Judith Weir and many other contemporary composers have not only been performed but also have been warmly received. I mention this to counter the old canard that the festival is dominated by conservative tastes.

That said, Simon Carpenter’s overall narrative serves as a welcome reminder that throughout its history the Three Choirs Festival has willingly embraced music that was new at the time it was first heard at Three Choirs, even if many pieces were, to our twenty-first century ears, very conservative. Messiah was given at a Festival less than 20 years after its first performance, while Elijah and The Dream of Gerontius became part of the Festival tradition within a couple of years of their respective premieres. Arguably, the Festival remained excessively bound to some core repertoire; Messiah and Elijah are both great works but they were regularly included, to the exclusion of other pieces, for too long. However, in the twentieth century and the present one the Festival has demonstrated an ever-increasing willingness to support living composers and to expand its repertoire horizons. Carpenter reminds us that the various cathedral Directors of Music from the start of the twentieth century onwards have all played their part in this regard. My eye was caught by a remark, which he quotes, made by Sir Herbert Brewer, Organist of Gloucester Cathedral from 1896 until he died in 1928. Looking back on the programme he devised for his first Festival, in 1928, Brewer said this: “I pointed out that if musical interest was not maintained, and if the programmes contained no novelties, the Festivals would soon cease to attract, and would pass away like other worn-out institutions”. Well, the Three Choirs Festival has not passed away; it remains in good heart nearly 100 years after Brewer’s death.

I enjoyed Simon Carpenter’s book very much. He has a clear, engaging style and his narrative is succinct. The book is evidently the result of a lot of careful and detailed research. As I read it, I felt I was in the hands of an experienced guide, who knows his subject very well and is keen to share his knowledge. His history of the Three Choirs Festival does not supersede the Boden/Hedley volume – such was not his intention, I feel sure – but it nicely complements that earlier survey. It is generously illustrated with a wide selection of relevant and evocative pictures.

This excellent book offers a lively and perceptive introduction to the world’s oldest music festival.

John Quinn

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free