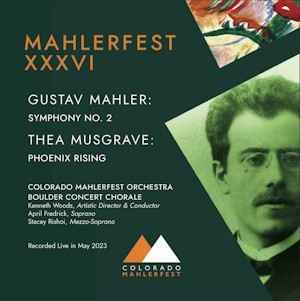

Thea Musgrave (b. 1928)

Phoenix Rising (1997)

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 2 in C minor ‘Resurrection’ (1888)

April Fredrick (soprano); Stacey Rishoi (mezzo-soprano)

Boulder Concert Chorale

Colorado MahlerFest Orchestra/Kenneth Woods

rec. live, 21 May 2023, Macky Auditorium, Boulder, USA

Colorado MahlerFest [2 CDs: 105]

Before considering this recording, it may be helpful if I just sketch in the background to the Colorado MahlerFest. It was founded in 1988 by the conductor Robert Olson, who had been a pupil of Hans Swarowsky in Vienna in 1973, as a Fulbright scholar. After his Vienna studies, Olson joined the staff at the College of Music at the University of Colorado in Boulder. He became the music director and conductor of the opera programme and associate conductor of the orchestras. Each year the festival which he founded presents a performance of one Mahler symphony and there’s also a programme of chamber concerts, lectures, symposia and other activities, with Mahler and his music as the principal, but not sole, focus. Olson continued as artistic director and conductor of the orchestra until 2015 when he retired at the conclusion of the 28th Festival. The following year, Olson was succeeded as artistic director by Kenneth Woods. The MahlerFest has become sufficiently highly regarded that in 2005 the International Gustav Mahler Society presented the Festival with its Gold Medal. The performances here preserved were given at a concert during MahlerFest XXXVI in 2023.

I think I should also say something about the orchestra that we hear in these performances. I made some enquiries, to which Kenneth Woods himself replied. I quote from his reply with permission. “We started to re-structure [the orchestra] in 2018 based on models I’d seen work well at Aspen, Scotia Festival and a few others. The orchestra is led by a group of “Festival Artists” who are experienced, top-tier professionals. Some are orchestra principals, some are professors at music schools or conservatories, some are chamber musicians. They serve as principals in the orchestra, with quite a lot of say in how their sections develop and in recruiting, and also play chamber music and do some masterclasses. Most of the rest of the orchestra is a mixture of conservatory/music school students and early career professionals, for whom MahlerFest provides a chance to learn some great repertoire and make connections with both their peers and mentors. At this point, the orchestra has a strong family vibe, and I would guess that we get about 85% of the orchestra returning year-to-year. Of course, for some of the younger players, they ‘graduate’ as they pick up jobs or family commitments. The consistency year-to-year is important because it means we’ve got an orchestra that knows a lot about Mahler’s style and the peculiarities of Mahlerian performance practice (including my own views on it!). It’s been wonderful to see how each year, we seem to pick up right where we left off and are able to build on what we did over the previous years. It’s mostly a US group but we generally have a small contingent of UK colleagues each year, and quite a few of the American-based students are originally from elsewhere around the globe.” I think that extensive quote is very relevant as background. Having listened to these performances, I can attest that the standard of playing is highly accomplished. Furthermore, there’s a palpable sense of commitment and that the orchestra is relishing the experience of exploring Mahler’s music collectively.

Before the Mahler performance, though, there’s another work to consider. Nowadays, it’s quite usual for a work of the length of Mahler’s Second to form an entire concert programme. However, Kenneth Woods and his players prefaced their account of ‘Resurrection’ with a performance of a demanding late twentieth-century score, Thea Musgrave’s Phoenix Rising. The opportunity to experience this Musgrave score again was a considerable draw for me. I first got to know it when I reviewed the 2018 Lyrita studio recording, which was the work’s debut on disc. I was seriously impressed by that 2018 recording and the present account led by Kenneth Woods has further increased my admiration for the work. I had forgotten, until I looked again at the Lyrita booklet, that Phoenix Rising was a BBC commission and that its premiere in 1998 was one of many important first performances led by the late Sir Andrew Davis.

The score is in five sections – ‘Dramatic’ – ‘Desolate’ – ‘Aggressive’ – ‘Mysterious’ – ‘Peaceful’; these are followed by a short coda, ‘Flowing and luminous’. The work is scored for a large orchestra and contains important solo roles for two players. As the composer explained in her programme note for this performance, “Throughout the work, timpani represent the forces of darkness, and a solo horn (at first off-stage) the distant voice of hope that eventually grows to signify rebirth and life.” She also tells us that “The use of physical spacing in the positioning of the orchestra underlines the drama; accordingly, soloists are positioned both on and off stage, and four percussion players are widely spread around the back of the orchestra.” One thing she doesn’t mention is that the ‘Desolate’ section includes a key role for solo cor anglais. I was interested to see that Thea Musgrave puts the length of the piece at “about 23 minutes”. I mention that because William Boughton takes 21:05 in his Lyrita performance and Kenneth Woods takes 19:23. I don’t suggest for a second that either conductor is “wrong” but the timing disparities from the composer’s estimation are interesting. Never did I feel that the Woods performance was unduly hasty; rather, I admired greatly the dramatic urgency and intensity of his conducting.

I described the piece in some detail in my aforementioned Lyrita review. So, on this occasion I will content myself with saying that when I looked again at that review after hearing this Colorado performance, I found that my notes tied in nicely with what I had written back in 2019. This performance led by Kenneth Woods is gripping and the orchestra play the piece incisively and with great virtuosity. Phoenix Rising is a terrific piece and I’m delighted that it has achieved a second recording – and such a fine one. I hope that anyone acquiring these discs for the Mahler and encountering Musgrave’s score for the first time will be as impressed by it as I am.

After the intermission, Woods and his orchestra returned to play Mahler’s huge symphony. To the best of my recollection, though I’ve heard Kenneth Woods conduct many times, both live and on disc, I’ve not previously experienced him in Mahler. In this performance he shows very impressive Mahlerian credentials.

Right from the outset, he establishes great tension in the first movement, tension which is sustained throughout. I liked his approach to the first few minutes of the work; his pacing seems very well judged and he ensures that the playing is weighty and strong. When Mahler diverts for a while into a nostalgic reverie (6:05 and again just after 17:00) I wondered if Woods’ tempo was just a fraction on the slow side and again, he is very measured indeed in the short episode at 12:09. However, these are isolated examples; overall, I found myself thoroughly convinced by his tempo selection, by his approach to the movement and by his evident grip on its structure. The orchestra is very fine indeed; not only is the playing exciting but in addition countless little nuances are observed, hugely to the music’s benefit. This is a considerable account of Mahler’s great funeral march; it made me eager to follow Woods on the rest of this journey.

The Andante moderato is taken quite swiftly. Some might feel the speed is a little too fleet but I like it, not least for the flow which is imparted to the music. The impression is affectionate and I admire the lightness of touch that I hear in the music making. The stronger episode (4:28 to 7:00) is vigorously projected and then Mahler reverts to the graceful mood in which he opened. This is a delightful account of the movement. The third movement is no less successful. Here, the pithy, sardonic nature of Mahler’s writing comes out in an ideal and idiomatic fashion. There’s lots of well-pointed playing to admire as well as excellent attention to detail. At the premonition of the finale (7:53), Woods whips up the tempo excitingly. Thereafter, the concluding pages are expertly handled.

In ‘Urlicht’ we hear the mezzo, Stacey Rishoi, who is American, I think. I’ve not encountered her before (though I have heard and admired her fellow soloist, April Fredrick on several occasions). Ms Rishoi sings well. Her tone is warm, the voice is focussed and her words are clear.

Woods unleashes the vast finale in thrilling fashion. His account of this huge movement is dramatic, as one would hope, and, crucially, he never loses sight of the overall structure. The various off-stage effects, including the grosse Appell, are very well managed. At 9:58 the two percussion crescendi are thrilling; Woods makes the first one particularly long and suspenseful, which I like; I always feel cheated if a conductor doesn’t make the most of this moment. The extended quick march that follows is highly energetic. Later in the movement, the point at which Mahler tips us over the abyss (16:16) is tremendously dramatic; the pages leading up to that point have been a proper white-knuckle ride. I’m afraid I find the first entry of the choir (‘Aufersteh’n, ja aufersteh’n wirst du, mein Staub’) a little disappointing. The singing is distinct, as it should be, but it’s not sufficiently hushed; there’s not enough of a sense of awe. I don’t know whether this happens because the Boulder Concert Chorale sing fractionally too loudly or because the microphones were placed too closely to them but the necessary frisson isn’t quite achieved. Soprano April Fredrick sings beautifully – at the risk of an outrageous pun, I’m tempted to say that her voice emerges from the choir like a Phoenix rising. Having been a bit critical of the choir I should balance that out by saying that towards the movement’s end, when they proclaim fortissimo ‘Aufersteh’n, ja aufersteh’n wirst du mein Herz, in einem Nu!’ they give their all, singing as if their lives depend on it; that is a properly spine-tingling moment, as it should be. The symphony’s tumultuous conclusion is greeted with a prolonged and vociferous ovation, including, I’m afraid, plenty of the ‘whoops’ which seem to be so de rigeur these days. I’m not surprised by the audience reaction; I’m sure the performance made a terrific impression in the hall. And, indeed, it impresses on disc too. Kenneth Woods conducts a very fine and exciting account of ‘Resurrection’ and his musicians respond to his galvanising and idiomatic direction with great skill and commitment.

The recorded sound is very good indeed. Audio engineer Joathan Galle has done a fine job, conveying the impact of the performances and also making a great deal of detail audible. As far as I’m aware, the CD version does not have a booklet per se but if you purchase either the CD or the download version of this album from the Colorado MahlerFest website you can access the full Festival programme, which includes detailed notes on both works.

This concert was clearly a great occasion in Boulder, Colorado and I’m delighted that these two very fine performances were recorded and are now preserved and available to a wider audience. The Mahler performance is well worth the attention of all devotees of the composer while the coupling of Thea Musgrave’s exciting piece adds considerable extra value.

My colleague, Lee Denham has already reviewed very favourably the recording of the 2021 MahlerFest performance of Mahler’s Fifth, also conducted by Kenneth Woods. I hope to appraise some other recordings from this source in the coming weeks.

Availability: Colorado MahlerFest