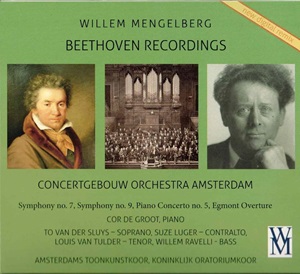

Willem Mengelberg – Beethoven Recordings

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Cor de Groot (piano), To van der Sluys (soprano), Louise Luger (contralto), Louis van Tulder (tenor), Willem Ravelli (bass)

Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam/Willem Mengelberg

rec. 1940-42, Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

The Willem Mengelberg Society, The Netherlands WMS2023/01-02 [2 CDs: 155]

This all-Beethoven 2-CD set is one of two which have arrived from a source previously unknown to me as one which issued CDs. The present incarnation of The Willem Mengelberg Society, The Netherlands, took over from a previous Mengelberg Society in 2014, and publishes magazines several times a year. There are downloads of all issues from the first one in 1987 to 2021 (issue 131 on the society’s website. They are, of course, entirely in Dutch, which certainly limits my own ability to access their contents, but they appear to be full of very interesting content if you are able to do so. The Society Webshop lists this and the Mahler and Strauss issue to be reviewed shortly, and also the 1939 Bach St Matthew Passion, which, as I write, has not been submitted for review. All the items in this set have been issued before, so I do not intend to review them musically at great length, though I will give an opinion on the transfers of this new issue at the end.

The first CD begins with the 7th Symphony, which is one of the three Beethoven symphonies which Mengelberg did not record commercially (the others being the 2nd and the 9th, this latter being the other symphony in this set). Both of the symphonies here are from the complete cycle he gave in the Concertgebouw in 1940. The full cycle was, I think, first issued by Philips on LP in 1977 (6767 003) and reissued on CD (462 626-2) in 1998. Music and Arts issued the full cycle in about 1997 (MACD1005), Archipel in 2003 (ARPCD 0192), Andromeda in 2007 (ANDRCD 5040) and Pristine in about 2010/11 (PABX008). There will undoubtedly have been other issues as well, though as far as I can find, none of the previous incarnations of any of the performances on these CDs has been reviewed on MusicWeb.

The introduction to the first movement of the 7th Symphony has a marvellous trenchancy and character, with surprisingly little rubato, and the Allegro itself is full of vitality. There is less rubato and string portamento than might have been expected, but it is an entirely convincing performance. The basic tempo of the Allegretto is quite swift, and here we see more of the Mengelberg of popular perception. In the first statement of the theme there is plenty of rubato and a pesante accent on the first note of each phrase, which I don’t find particularly convincing. Fortunately, the agogics are used far less as the movement progresses and the music flows much more convincingly. It is a very emotionally overt performance, rather than the melancholy of most performances. The Scherzo again has tremendously vitality and momentum, and though rubato continues to be used relatively lightly, the trio is taken considerably slower than the rest of the movement. The Finale is of a piece with the rest; there is a little more freedom with tempo, but the same excitement and momentum. The accelerando in the final bars is a very Mengelbergian moment. I find this one of the most convincing and enjoyable of Mengelberg’s Beethoven performances.

The Emperor Concerto performance was discovered only in the late 1990s and issued by APR in 2001. The notes for the APR CD (APR 5612) tell us that the performance came from a tape copy of the original acetates requested by the pianist “just before one of the original discs kept at the Dutch Radio Archive was broken.” Unfortunately, the present issue does not give any information about the original sources of any of the performances, but the sound quality is considerably better than the APR issue. So whether the Netherlands Society had access to the surviving acetates I do not know. What I can say is that there is no section where the sound is noticeably poorer than anywhere else, so perhaps I am mistaken in my assumption that they had access to the acetates. But this transfer allows a much more vivid and direct engagement with the performance than the APR.

Mengelberg was always a superb accompanist – I know of no better performance of the orchestral part of the Bruch Violin Concerto than that of his live 1940 performance with Guila Bustabo. Cor de Groot and Mengelberg, despite a 43-year age difference, apparently got on very well, and certainly de Groot’s piano playing is entirely of a piece with Mengelberg’s conducting. According to the booklet with the APR CD issue, Mengelberg told his young pianist, “Play as you like, we will not argue,” and, indeed, there seems to be an absolute meeting of minds in this performance. De Groot employs exactly the same sort of tempo and dynamic flexibility as his conductor. This can be seen from the very start in Mengelberg’s very dramatic first chords, continued perfectly by de Groot’s free, improvisatory cadenzas. Although de Groot was born in 1914, this is a performance with a greater similarity to the Lisztian tradition of the late 19th century, as exemplified on record by the Emperors of Frederick Lamond and Eugene d’Albert, than to the Schnabel-inspired rethink which had become the norm by 1940. It is impossible to imagine its like being given today. In the slow movement the tempo is quite swift and flowing, and, like the slow movement in the 7th Symphony, is more overtly emotional than the sort of introspective reflection which Schnabel embodies. De Groot is much more rhetorical, and the downside to this is that at times, for example in the accompanying piano passage work beginning at 5:50 into the slow movement, the result can seem a little perfunctory and uninflected. The transition from the slow to final movements is absolutely Lisztian in its drama. There is no gradual awakening in the bridge passage; the first two piano phrases are played at the same quiet dynamic level and almost uninflected. Before the third phrase, de Groot makes an agogic pause and then explodes into the finale proper like a greyhound out of the traps. Throughout the movement, de Groot gives unexpected chords a similar explosive treatment – this really is Beethoven in what used to be called his “unbuttoned” mood, almost manic in its excitement and dynamic force. However the two interpreters also give a performance full of detail – for example, in the phrasing of the string chords between 5:22 and 5:40. This is a remarkable, fascinating performance.

The second CD begins with the Egmont Overture from 1943. In the introduction, Mengelberg makes great contrast between the imperative string phrases and their keening woodwind responses, slowing considerable for the latter and moulding them with real emotional weight. When the Allegro begins, we see again the conductor’s wonderful ability to generate momentum; it has the trenchancy of Toscanini without the inability to relax. The coda is positively cataclysmic.

The 9th Symphony is a marvellous performance. The first movement is highly dramatic, almost violent; there is none of Furtwängler’s metaphysics in the opening, Mengelberg is far closer in feel to Toscanini, though, of course, with a constant rhythmic flexibility that would have given the Italian an attack of the vapours. The rubati, however, never dissipate the momentum; the movement flows inexorably throughout. The Scherzo continues the dramatic momentum of the first movement. The slow movement, while slow by the standards of today’s jog-trot performances, at 15.38 is far closer to Toscanini’s fourteen minutes than to Furtwängler’s nineteen. The tempo remains flexible, most startlingly in the sudden increase in speed at 9.33 into the movement. My own taste is for a slow tempo in this movement, so this is less to my taste than the other movements, but there is still much of interest and beauty. The Finale has the drama, momentum and flexibility that the other movements would lead one to expect; it is a superb performance (if you ignore the absurd transformation of the final bars into the motto theme of the 5th Symphony’s first movement. This is more than even I can accept). The solo quartet of Dutch singers, who were pretty-well unknown outside Holland even in their day and are now barely names even to enthusiasts for historic performances, are actually pretty good. The tenor line severely strains Louis van Tulder at times, and Willem Ravelli is not the most resonant of basses. But then is there ever a flawless performance of the impossible solo parts outside the multiple takes possible in the studio? I’ve heard many a bigger name make much more of a mess of this movement.

I expect that, like me, many of you who are reading this review will already have these performances and are reading this review largely to find out whether the new transfers are worth investing in. Well, I can sum up my judgment of them in one word: outstanding. In all honesty, I had no expectation that they would be better than (or even as good as) the Pristine issues, but to my astonishment they are. As I mentioned earlier, there is no information at all about the provenance of the originals from which these transfers were made, only that they were made originally by Hans van Ispelen, who died in 2014, who was a “fervent music lover, amateur musician and gifted sound restorer. However, to take advantage of new advances in digital technology, they were treated or restored anew by Jochem Geene… [who] brought back the original acoustic of the hall and created with State-of-the-Art software a quasi-stereo image to get as close as possible to the original listening experience.” This is somewhat vague, to say the least, but I was able to do direct A/B comparisons with the Philips CD and Pristine issues of the 7th Symphony, and the APR issue of the Emperor concerto.

From the source information on the Pristine CD, it seems that Andrew Rose’s sources were the Philips LP issues, which by now must be getting on for 50 years old. He has, of course, made an excellent job in his restoration, but the congestion to be found in orchestral tutti is there on the Philips issues, and is not, I think, anything that he could substantially mitigate. I can only come to the conclusion that the present issue had access to the original acetates and was able to make much better transfers of them. There is no surface noise at all – something that the Philips issues did not bother about (I seem to remember in places some very annoying scratches which ticked a number of times and which would not have been difficult to remove even 50 years ago) and the tuttis have markedly cleaner sound with almost no congestion. The dynamic range is very wide and the sound picture generally is remarkably realistic. The “quasi stereo image” mentioned in the extract above from the liner notes is very apparent, and very convincing, in a number of places, for example about three minutes into the first movement of the 9th. I have only one slight reservation about the transfers. On occasions where there is a silence in the music it becomes a total, anechoic-chamber-type silence, as though the signal had been cut off, which I would think is the result of over-filtering. It is really quite disconcerting, and is particularly noticeable in the Scherzo of the 9th Symphony (e.g. 4:37, 9:08, 9:12 and 9:25).

To sum up, if you do not have these performances already, then do not hesitate to buy this issue: these are marvellous performances in the best available sound. Even if you do have them, I don’t think you will regret buying this issue, given the sonic improvement.

Paul Steinson

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site

Also available from : The Willem Mengelberg Society, The Netherlands

Contents

CD 1

Symphony No 7 in A major, Op 92, rec. 25 Apr 1940

Piano Concerto No 5 in E-flat major, Op 73, Cor de Groot (piano), rec. 9 May 1942

CD2

Egmont Overture, Op 84, rec. 29 Apr. 1943

Symphony No 9 in D minor, Op 125, To van der Sluys (soprano), Louise Luger (contralto), Louis van Tulder (tenor), Willem Ravelli (bass), rec. 2 May 1940