The Boy and the Magic – L’enfant et les sortilèges

Maurice Ravel, Colette and Gerard Hoffnung

by Len Mullenger

L’enfant et les sortilèges was Ravel’s second opera/ballet set to a libretto by Colette and premièred in 1925. It is total fantasy.

When I sat down with Annetta Hoffnung to prepare the MusicWeb’s Hoffnung site, she told me that Gerard had known this opera from an early age as his mother was so fond of it. Gerard found it so entrancing that he painted some imaginary scenes in full colour instead of his usual line drawings. He showed them to Colette and she wrote a short text to each painting so they could be published in a book. They had some difficulty finding a printer because they were in colour. Eventually, the book was published by Dobson Books in 1964. Used copies are expensive because it is the sort of book nobody willingly gives up. Annetta gave me my copy but she did say that two of the paintings had gone missing following an exhibition, so are not in the book.

I intend to go through the opera, scene by scene, illustrating it with Gerard’s paintings, extracts of the text in English translation and sound excerpts. I got to know this work through the 1961 recording conducted by Lorin Maazel and I will be using extracts from that recording to illustrate this article. I came across this recording in the record library in Leeds when I was just finishing my sixth-form studies. It had a beautiful gatefold cover bearing the libretto on the inner sides. When I bought my own copy, it had just a standard LP slipcase and I was very disappointed, so, I wrote to DG who replied that I must have seen the German cover and they sourced one for me. Are record labels so accommodating these days?

Unfortunately, it is no longer sold as a CD single, only as an mp3 file. However, Decca have a marvellous complete edition of Ravel on 14 CDs (4783725) and it is included in that. I waited for Presto’s box set sale to get mine in the first lockdown and have never regretted a penny of it; it is full of treasures (Ed. – it seems the CD version of the box set is no longer available but used copies of the single DG CD are readily available). I was recently lent by a MusicWeb reviewer a DVD of the Glyndebourne production. This, too, is difficult to source. However, I played all of it to a music group I run, who were totally unaware of the work and found it charming. That was when I decided to write this article to introduce it to a wider public.

The opera opens with a gentle meandering theme on two oboes. It is a warm afternoon and the plants and animals in the garden are at rest because there is no little boy to taunt and bother them.

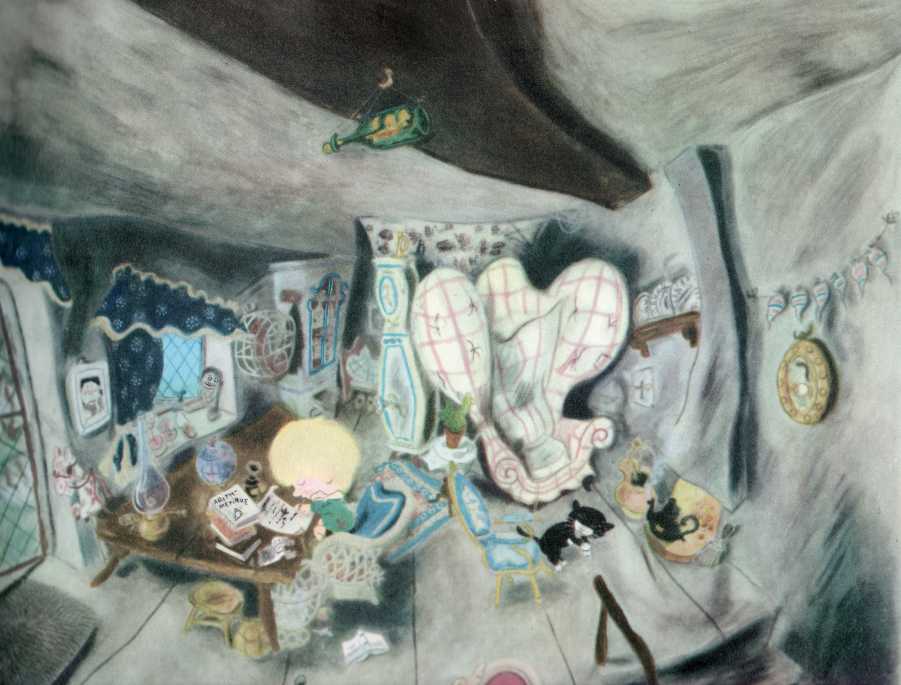

But inside the house, a very disconsolate child is being forced to get on with his homework.

The child is bored, so scratches away with his pen, but all he achieves is a large inkblot on the paper and the carpet. His mother comes in with some tea and is cross at what she sees. The child puts out his tongue at her, so is told he must stay in the room until supper time, with just dry bread and no sugar in his tea.

The child shouts:

I don’t want to learn my lesson

I want to go for a walk

I’d like to eat up all the cakes

I’d like to pull the cat’s tail.

And to cut off the squirrel’s.

I want to roar at every one

And put Mother in the corner

The child becomes very angry and destructive. He smashes the cup and teapot off the table and they break into pieces. He assaults the caged squirrel with his pen nib. He pulls the cat’s tail.

I don’t like anyone

I’m really very naughty!

Naughty! Naughty! Naughty!

He climbs into the grandfather clock and swings on the pendulum until it breaks off in his hands. He tears the pages out of his school book and exercise book, all the time screaming

‘Hurrah! Hurrah! No more lessons, no more homework, I am naughty and free!’

He pokes the fire and empties the kettle into it, producing clouds of steam and ash, then grabs the wallpaper, pulling away great strips of it. This is where the magic happens, to teach the child a lesson. Things come unexpectedly to life. When he tries to sit in the armchair, it shuffles away from him and dances a stately sarabande with a Bergère – a Louis XV chair.

ARMCHAIR

Your humble servant, Bergère!

BERGÈRE

Your servant, Armchair

ARMCHAIR

Now we’re forever

rid of this child

with his wicked heels

BERGÈRE

You see how relieved I am

etc.

Their sentiments are approved of by the Sofa, Settle, Ottoman and Wicker Chair. If the director has been imaginative enough, actor/dancers wear these pieces of furniture. They look real enough but the actor/dancers can still move around the stage.

The clock has lost his pendulum, so wheels onto the stage complaining that he no longer knows what time it is. Both his hands are whirling round and he is chiming uncontrollably. He asks if he can hide his shame by standing in a corner, facing the wall.

Ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding!

And again, ding, ding, ding!

I can’t stop myself from chiming

I no longer know the time!

He’s taken away my pendulum!

I have a terrible tummy ache!

And a draught right in my middle

And I am beginning to wander!

etc.

George Gershwin had visited Ravel for composition lessons but when Ravel learned how much Gershwin made in a year, he said Gershwin could teach him a thing or two. As a result, Ravel included some Americanisms.

We reach the scene where the tea pot and mug come together, and as the teapot is Black Wedgwood and the cup is Chinese, we get a foxtrot but with Chinese malapropisms and sung in strangled English. The teapot threatens to punch the boy.

TEAPOT

How is your mug

CUP

Rotten!

TEAPOT

Better had

CUP

Come on!

TEAPOT

Black and costaud

Black and chic, jolly fellow,

I punch, Sir, I punch your nose.

I knock you out, stupid chose!

Black and this and vrai beau gosse (real handsome)

I box you, I marm’lade you.

CUP (pointing at the boy threateningly)

Keng-ça-fou, Mah-jong

Keng-ça-fou, puis’-kong-kong-pran-pa,

Ça-oh-râ, Ça-oh-râ …

Cas-ka-ra, harakiri, Sessue Hayakawa,

Hâ Hâ! Ca-h-râ toujours l’air chinoâ

CUP and TEAPOT

Hâ! Ca-h-râ toujours l’air chinoâ

Ping, pong, ping

THE CHILD (horror-stricken)

Oh! Ma belle tasse chinoise!

The boy sees what he has done and goes to the fire for comfort but the fire leaps out of the fireplace and announces that it warms only good children, not bad, and chases the boy round the room.

Away! I warm the good but burn the bad!

Foolhardy little savage! You’ve insulted all the friendly household gods who held the barrier between you and misfortune! You’ve brandished the poker, upset the kettle, and scattered the matches!

Beware! Mind the dancing flame!

You’ll melt like a snowflake on its scarlet tongue!

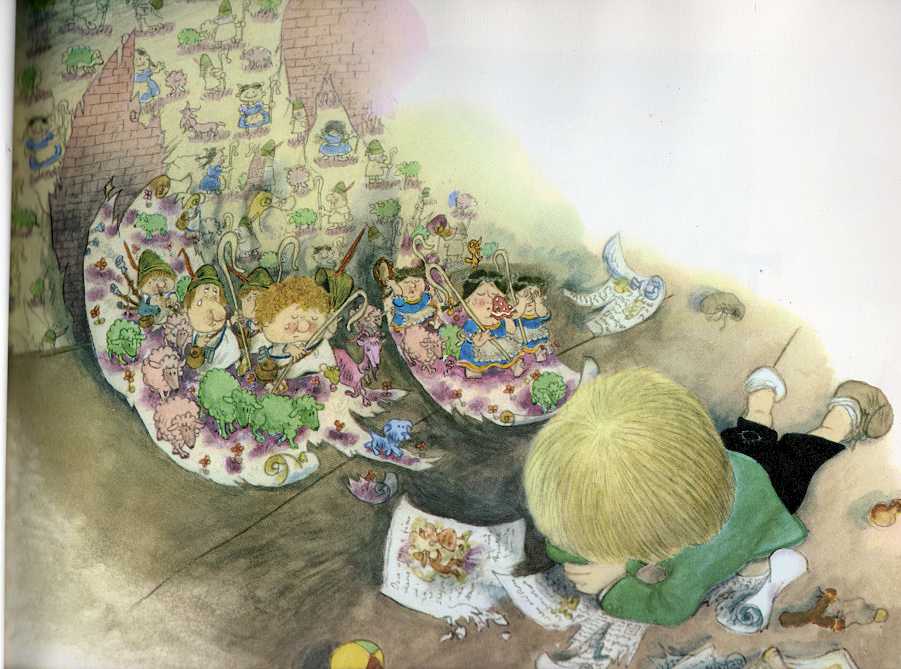

From the shredded wallpaper comes a procession of shepherds and shepherdesses with multi-coloured animals accompanied by pipe and tambourine. They say farewell to each other because they have been separated by the ripped wallpaper.

Farewell Shepherdesses

Shepherds farewell

No longer shall we pasture our green sheep

on the purple grass

Alas our violet goat

Alas for our gentle pink lambs

Alas for our purple cherries

and our blue dog!

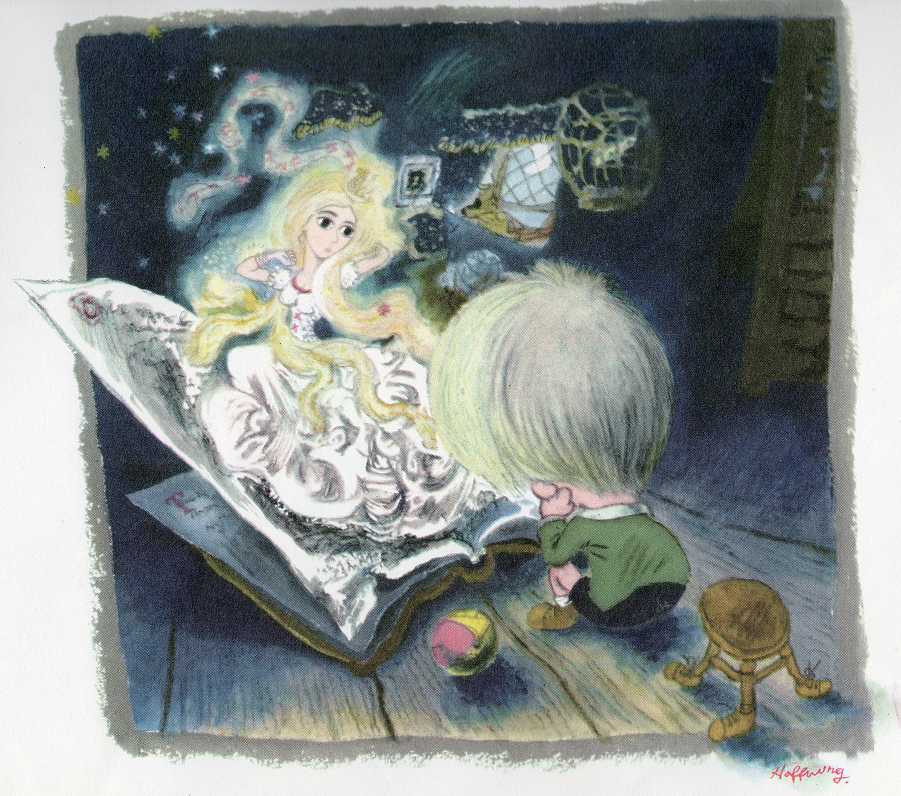

The distraught child is lying on the floor, on bits of torn paper from a book with his head in his hands. From one piece of paper rises a princess whose tale he had been reading. But he has torn up the book so what is going to happen to her? There is no end to her story. Is the evil enchanter going to get her? The child says he would defend her with his sword, if only he had one. The floor opens up and the Princess calls out, ‘Help, Sleep and Night want to take me back again’.

CHILD

Ah! ”tis she! ’tis she!

PRINCESS

Yes, ’tis she, your fairy princess

She for whom you called out in your dream

Last night.

She whose story, begun yesterday,

Kept you awake so long

You were singing to yourself ‘She is blonde

With sky-blue eyes’

You sought me in the heart of the rose

And in the scent of the lily

You sought me, little love,

And since yesterday I’ve been your

first love.

CHILD

Ah! ’tis she! ’tis she!

PRINCESS

But you’ve torn up the book

What is going to happen to me?

Who knows if the evil enchanter

Isn’t going to put me to sleep for ever

Or dissolve me into cloud

Tell me, aren’t you sorry never to know

The fate of your new love?

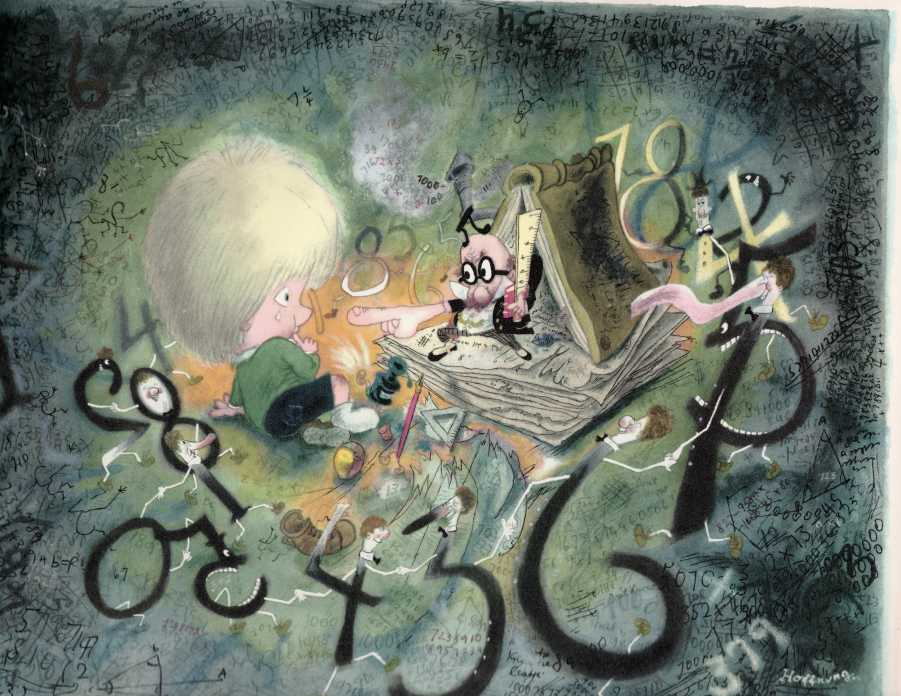

The boy is disconsolate and shoves some books with his foot. ‘Dull and dreary,’ he says. Along comes Arithmetic – a funny little man with a Pi on his head, a tape measure for a belt and armed with a ruler, with numbers dancing round him. He torments the boy with manic, quick-fire arithmetic.

CHILD

Nothing .. all these are school books

Dull and dreary

ARITHMETIC

Two taps run into a tank!

Two slow trains leave a station

At twenty minutes intervals

Val, val, val

A peasant woman,

Woman, woman, woman

Carries all her eggs to market!

Once a haberdasher,

Dasher, dasher, dasher,

Sold six yards of cloth!

CHILD

Good Lord! It’s Arithmetic!

ARITHMETIC AND A CHORUS OF NUMBERS

Ticker, ticker, ticker!

Four and four, eighteen

Eleven and six, twenty-five

Seven times nine, thirty -three

CHILD

Seven times nine, thirty-three?

NUMBERS

Seven times nine, thirty -three?

CHILD (Boldly exaggerating)

Three times nine, four hundred!

ARITHMETIC

Millimeter,

Centimeter,

Decimeter,

Decimeter,

Hectometer,

Kilometer,

Myriameter, not a miss!

Oh, what bliss!

Millions,

Billions,

Trillions,

And frac-cillions

NUMBERS

Two taps run into a tank etc.

Three nines, thirty-three!

Twce six, Twenty-seven!

Four and four! Four and four!

Four plus six, fifty-nine!

Twice six, thirty-one

Five fives, forty-three!

Seven and four, fifty-five etc.

The child has been dragged into a giddy dance and collapses on the floor as Arithmetic and numbers fade away.

Four plus four, eighteen!

Eleven and six, twenty-five!

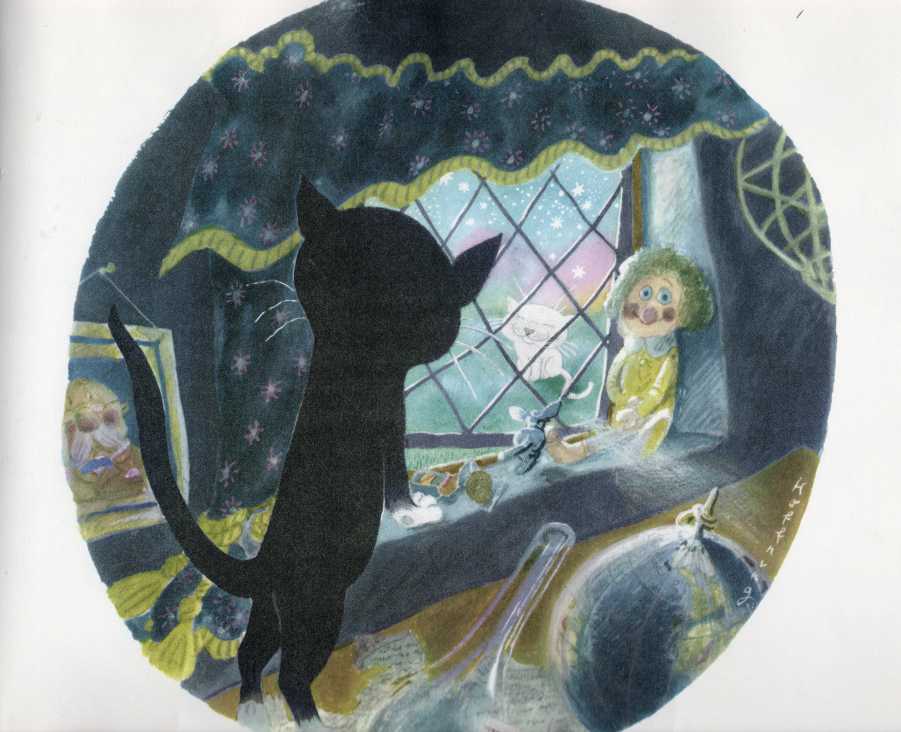

We now come to the most famous scene in this opera: the cat duet. The stage instructions are that the black cat crawls out from under the armchair. He stretches himself, yawns and starts to wash his fur. Then he plays with a ball of wool. He approaches the child to try to play with his blond head as with a ball.

CHILD

Oh! My head! My head!

It’s you, pussy. How big and dreadful you are. You speak, too, no doubt?

The cat shakes his head because he is not able to speak and then spits at him. He leads the way to the garden where he has spied a white Lady cat.

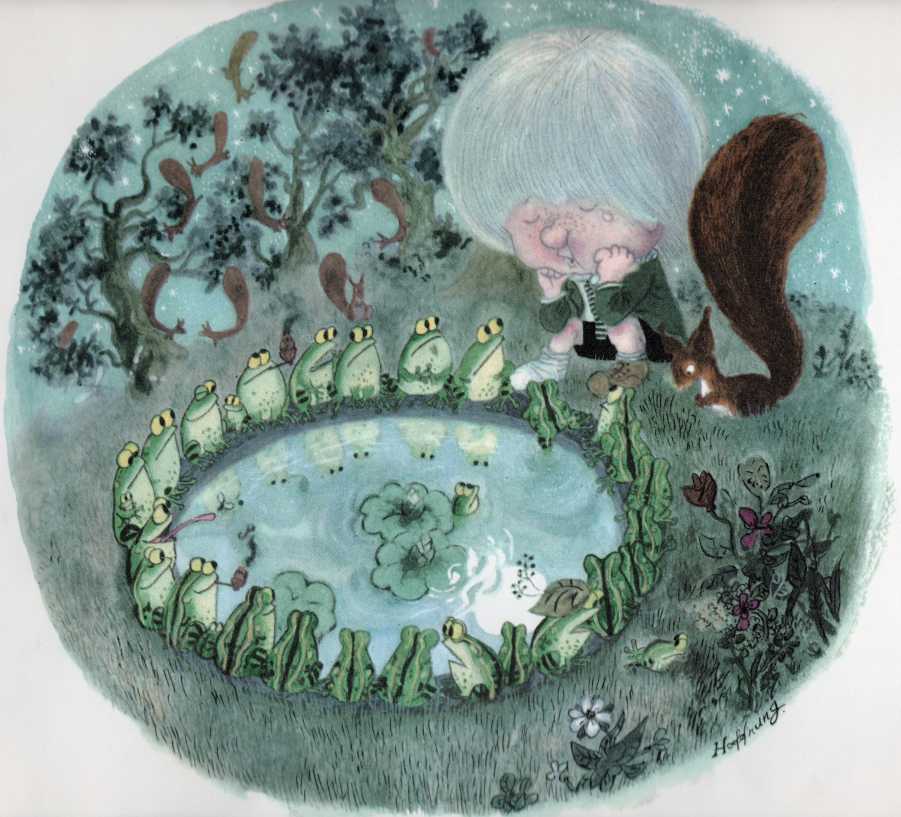

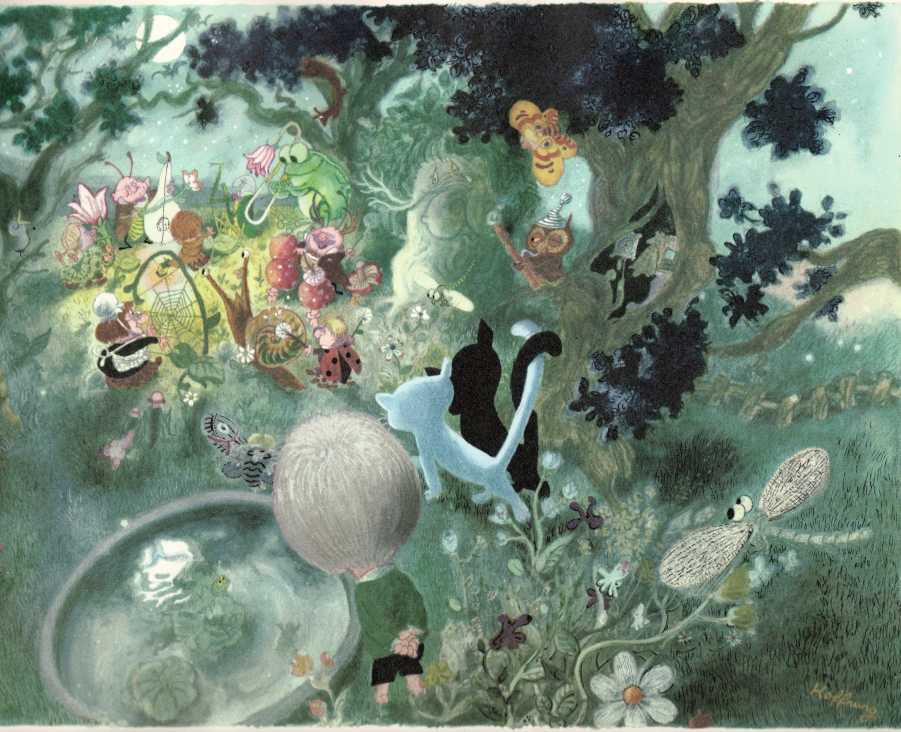

The whole scene changes to the garden which is flooded by moonlight. A chorus of frogs can be heard from behind the scenes.

Trees, flowers, a little green pool, a fat tree trunk covered in ivy. The music of insects, frogs and toads, the laughter of screech owls, a murmur of breeze and nightingales.

Ah! What happiness you find again in the garden.

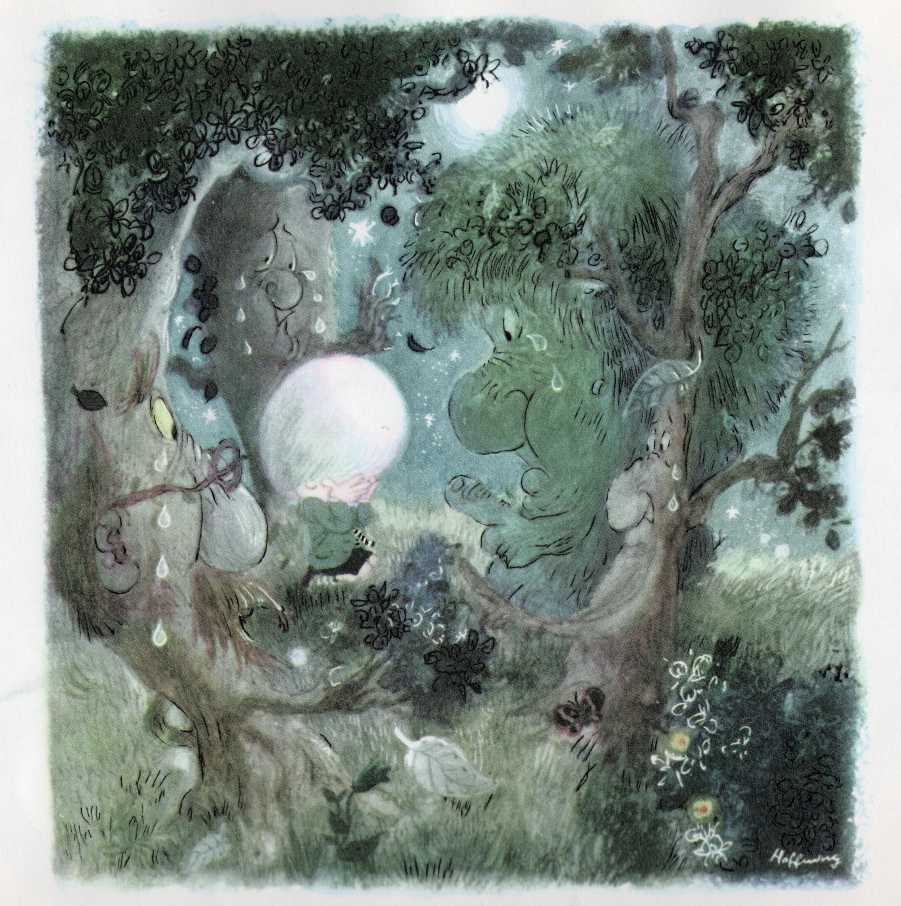

The child leans against a tree trunk, which groans.

TREE

My wound! my wound!

CHILD

What wound?

TREE

The wound you inflicted yesterday on my

side, with the knife you pinched. Alas!

It’s still bleeding sap

OTHER TREES groaning and swaying

Our wounds, our wounds. They’re still fresh and go on bleeding sap.

Naughty Child!

The child leans his cheek against the tree in sympathy. A dragonfly is appealing for her mate she has lost, as is a bat. The boy had impaled the dragonfly on a pin and pinned it to the bedroom wall. The child had also killed a bat and is now frightened and cries out for mercy.

The child realises that all the animals are happy in the garden and he feels remorse and suddenly lonely. He calls out ‘Maman’. On hearing that, the trees and animals turn against him, menacingly.

Ah it’s the child with the knife!

It’s the child with the stick!

The bad child with the cage!

The bad child with the net!

The child who loves no-one!

Shall he escape?

No he must be punished!

I’ve my talons!

I’ve my teeth!

I’ve my clawed wings!

Let’s unite, let’s unite!

There is a big struggle, with all the animals pushing and pulling to get to the boy. He is passed from animal to animal and then they seem to forget about him, casting him to one side whilst they carry on fighting among themselves. A wounded squirrel flops beside the boy with a sharp cry. The animals are shamed and stilled, and all pull back. The boy takes out a handkerchief and dresses the squirrel’s paw but the he himself is also injured.

AN ANIMAL

He has dressed the wound

ANOTHER ANIMAL

He has dressed the wound. He has bound the paw, stopped the bleeding

OTHER ANIMALS in chorus

He has dressed the wound

He’s in pain. He’s wounded, he’s bleeding

… He dressed the wound. His hand must be bound up, the bleeding stopped. What’s to be done

He knows how to cure ills. What’s to be done? We’ve wounded him.

What’s to be done?

AN ANIMAL

A moment ago he was calling

ANIMALS

He was calling

AN ANIMAL

He cried out a word, just one word

“Mama!”

AN ANIMAL

He’s silent. Is he going to die?

ANIMALS

We don’t know how to bind his hand…to stop the bleeding.

AN ANIMAL pointing to the house

That’s where we will find help! Let’s take him back to the nest!

They should hear there the word he cried out a moment ago

Let‘s try and call it.

The animals lift the boy and carry him to the house, shouting “Mama” louder and louder.

The opera ends with the child simply calling “Mama”.

The “Maman” that ends Colette’s libretto is a cry of loss and pain: Colette’s, when she wrote the text, Ravel’s, when he came to compose the music. It was the cry of all those wounded soldiers that Colette saw at her hospital, that Ravel saw at the front. And it was the cry that gave this extraordinary opera an even more extraordinary afterlife. … Margaret Reynolds The Guardian July 2012

Recording

The Child: Françoise Ogéas

Maman, the Chinese cup, the dragonfly: Jeanine Collard

The sofa, the female cat, the squirrel, a shepherd: Jane Berbié

Fire, the princess, the nightingale: Sylvaine Gilma

The bat, the owl, a shepherdess: Colette Herzog

The armchair, the tree: Heinz Rehfuss

The clock, the male cat: Camille Maurane

The teapot, Arithmetic, the frog: Michel Sénéchal

Maitrise de la R.T.F, Choeurs de la RTF

L’Orchestre National de la RTF/Lorin Maazel

rec. 1961