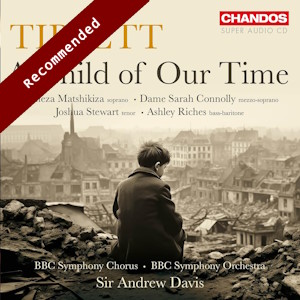

Sir Michael Tippett (1905-1998)

A Child of Our Time (1939-41)

Pumeza Matshikiza (soprano); Dame Sarah Connolly (mezzo-soprano); Joshua Stewart (tenor); Ashley Riches (bass-baritone)

BBC Symphony Orchestra & Chorus/Sir Andrew Davis

rec. 2023, Phoenix Concert Hall, Fairfield Halls, Croydon, UK

Text included

Chandos CHSA5341 SACD [64]

If you had asked a group of music lovers to name the conductor most closely associated with the music of Sir Michael Tippett, I suspect that most of them would have referenced Sir Colin Davis; that would have been my answer. However, shortly after the death of Sir Andrew Davis in April 2024, I read a warm, affectionate tribute to the late conductor by the Tippett biographer, Oliver Soden; this caused me to revise that view. Soden rightly recalled how effective Sir Colin had been in championing several of Tippett’s major pieces, including The Midsummer Marriage, and especiallyin the 1960s, when his advocacy got several works properly noticed. However, he went on to relate that Sir Andrew conducted even more works than Sir Colin – twenty-five – and maintained a strong interest in Tippett’s music throughout his life. Among his notable achievements was what I believe was the UK premiere of the vast cantata The Mask of Time, which was subsequently issued as a recording – I confess, I found both words and music utterly baffling; maybe I should try again. Soden said that Sir Andrew was planning to revive that work in 2025. A couple of days after reading that appreciation I came across a social media post by Soden in which he said that he had learned that Sir Andrew was listening to the slow movement of Tippett’s Concerto for Double String Orchestra when he died.

How poignant, then, that Chandos should have scheduled – some time ago, I’m certain – the release of this studio recording of A Child of Our Time just a few weeks after Sir Andrew’s death at the age of 80. I think I’m right in saying that the recording sessions were held shortly after a live performance at the Barbican in London; certainly, what we hear on this SACD sounds well ‘run in’ as a performance.

I first encountered A Child of Our Time (on LP) in Sir Colin Davis’s 1975 recording, made with a luxury cast of soloists (review). Much later, I acquired his 2007 LSO Live version, which I think is now only available in an anthology of a selection of Sir Colin’s recordings for that label (review). In between those two Colin Davis versions I heard the composer’s own 1991 recording with the CBSO (review) and also Richard Hickox’s recording, made the following year (review). Interestingly, Tippett’s own recording is quite expansive, playing for 69:19 while Hickox takes even longer; his performance takes 73:17. I must say, I have never thought that either of these performances drags but it’s notable that the two Colin Davis performances are, in terms of the stopwatch, rather tauter: the 1975 studio recording plays for 64:28 and the 2007 live version occupies a remarkably consistent 63:59. Simply in terms of duration, the new Andrew Davis account comes in at 63:48, which is pretty similar overall to Sir Colin’s timings.

Sir Andrew, like Sir Colin, was an extremely seasoned opera conductor and I feel that’s significant when we consider the pacing of their respective recordings. Neither of them neglects the reflective side of the work but both of them invest the music with a fine sense of urgency and drama when words and music demand it.

Though the background to the work is pretty well known, I think it’s worth summarising. Tippett, a lifelong pacifist, wrote A Child of Our Time between 1939 and 1941. He was inspired by an event which took place in 1938. A young Polish Jewish boy, Herschel Grynszpan, murdered a German diplomat in Paris and this was the excuse for the horrifying series of pogroms in Germany and Austria known collectively as ‘Kristallnacht’. (Mervyn Cooke details the background very thoroughly in his booklet essay.) Tippett devised his own libretto which reflects on these events and their consequences. An important element which Cooke brings out is that the tripartite structure of the libretto of Handel’s Messiah was to some extent Tippett’s model. A key structural device is Tippett’s inspired decision to weave into his work five African-American Spirituals in a way which is comparable to Bach’s use of chorales in his Passions.

Sir Andrew Davis has the benefit of a fine quartet of soloists. The one who was new to me is the South African soprano, Pumeza Matshikiza. I liked her very much. She employs quite a lot of vibrato to warm her tone, but never excessively so. And, unlike many sopranos that I’ve heard in the past, I didn’t find that the vibrato clouded her diction. She impressed me with her very first solo, ‘How can I cherish my man in such days…?’ Her touching rendition of the music brings out the sadness in both words and music and the top range of her voice is just gorgeous. As that solo draws to a close, she sets up quite beautifully the first Spiritual, ‘Steal away’, over which her keening decoration is ideally floated. Elsewhere in the work, Ms Matshikiza is no less impressive, even if she doesn’t shake my allegiance to the unforgettable Jessye Norman on the 1975 Colin Davis recording. Dame Sarah Connolly is ideally cast. All her solos are delivered with a fine understanding of the words and the musical idiom. I particularly admired the blend of rhythmic drive and expressiveness that she brings to ‘The soul of man is impassioned’ in Part III.

I thought the name of the American tenor Joshua Stewart rang a bell and then I read in his biography that he’d sung the work in a Birmingham performance conducted by Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla. I remembered then that I’d reviewed the concert in question for Seen and Heard; revisiting my review, I saw that Stewart impressed me on that occasion. He’s very good indeed in this recording. He brings ideally clear tone and diction to everything he does, including his contributions to the Spirituals. In his first aria, ‘I have no money for my bread’, he transmits the anguished mood in a very credible performance. Later, in Part II, he gives a heartfelt, eloquent rendition of ‘My dreams are all shattered in a ghastly reality’. Stewart’s involvement in this project is an excellent piece of casting. The bass soloist largely functions as the Narrator. Ashley Riches brings authority and fine commitment to his role, though I don’t think he matches the smouldering intensity of John Shirley-Quirk who sang for Colin Davis in 1975. He has a commanding presence in ‘Go down, Moses’. Towards the end of the work comes the Scena for the bass and the chorus, ‘The words of wisdom are these’. In many ways, this is, dramatically and emotionally, the dark heart of A Child of Our Time. This number is strongly delivered by Riches and the BBC Symphony Chorus; it’s very affecting.

Andrew Davis is no less well served by his chorus and orchestra. The BBC Symphony Chorus, trained for this assignment by Wesley John, sings excellently. Their contribution is full of commitment and attention to detail. That latter quality is in evidence right at the start in the first chorus, ‘The world turns on its dark side’. Here, I very much admired the choir’s attentiveness to dynamics and accents. With the BBC Symphony Orchestra being just as on-point, this means that the tension and foreboding in Tippett’s music registers powerfully. Just as noteworthy is the intensity which the BBCSC brings to the chorus ‘A star rises in mid-winter’ which opens Part II. In other places, the choir’s incisiveness in fast-paced music is very impressive. Crucially, they sing the five Spirituals excellently, ensuring that these numbers register as the emotional and structural pillars of the work. The BBC Symphony Orchestra is on top form, both collectively and individually, throughout. They bring out all the light and shade in the music and, above all, project the drama in the music very powerfully.

Presiding over all this is Sir Andrew Davis. He had a reputation for his genial manner – deservedly so, by all accounts – but this didn’t come at the expense of focus. As I indicated earlier, it seems to me that he paces the music very well indeed. His is a powerful, biting reading but he doesn’t in any way neglect the reflective side of the music. And his keen eye and ear for detail ensure that, working in collaboration with the Chandos engineers, the listener gets an excellent aural picture of Tippett’s score. Above all, it seems to me, Davis embraces and conveys the vision of Tippett’s words and music which are, dare one say, especially potent in these present days when our troubled world seems indeed to be turning ‘on its dark side’.

The recording was engineered by Ralph Couzens and produced by Adrian Peacock. They’ve ensured that we hear Tippett’s music projected with impact and clarity. Mervyn Cooke contributes an exemplary booklet essay.

I have to admit that, even though the work is relatively early Tippett, I struggled with A Child of Our Time for a long time. In recent years, however, I’ve come to appreciate it much more and this recording is one which, for me, along with the 1975 Colin Davis version (which still sounds very fine, nearly 50 years on) emphasises the musical and moral stature of the work.

This, then, is Sir Andrew Davis’s final completed recording project, though it was not intended as such: I understand that he and Chandos had another project in mind but, sadly, that was not to be. Since his death I’ve read that Chandos have some recordings ‘in the can’ of Sir Andrew conducting his own orchestrations of Bach organ pieces, but these are not sufficient to fill a disc; I hope a way will be found to issue them. This recording of A Child of Our Time is an impressive achievement and serves as a fine memorial to a distinguished British conductor.

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free