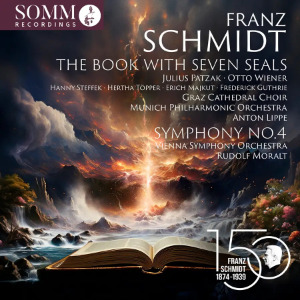

Franz Schmidt (1874-1939)

Symphony No. 4 in C Major (1933)

Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln (The Book with Seven Seals) (1937)

John: Julius Patzak (tenor); Voice of the Lord: Otto Wiener (bass)

Hanny Steffek (soprano); Hertha Töpper (alto); Erich Majkut (tenor); Frederick Guthrie (bass)

Franz Illenberger (organ)

Graz Cathedral Choir

Munich Philharmonic Orchestra/Anton Lippe

Vienna Symphony Orchestra/Rudolf Moralt (symphony)

rec. 7 September 1954, Musikverein, Vienna (symphony: mono); January 1962, Stefaniensaal, Graz (Book: stereo)

Somm Ariadne 5026-2 [2 CDs: 157]

In 2024 the musical world is marking the bicentenary of the birth of Anton Bruckner and the 150th anniversary of the birth of Arnold Schoenberg; so, the anniversary of another Austrian composer, born in the same year as Schoenberg, might easily be overshadowed. This CD release of what I understand are the premiere recordings of two of Franz Schmidt’s most important works is therefore timely.

Understandably, SOMM give precedence to Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln but I’d like to begin with the symphony, if only because that was the first work by this composer that I got to know. That was many decades ago (on LP) through Zubin Mehta’s fine Decca recording with the Vienna Philharmonic. Here, it’s the Vienna Symphony Orchestra who do the honours under the baton of the German conductor Rudolf Moralt (1902-1958). This recording was made under studio conditions, in the Musikverein, Vienna on 7 September 1954 and, SOMM tell us, it was first released on an LP by the Epic label. The recording is in mono but I don’t think that’s an issue.

The symphony is in one continuous movement, though this is divided into four clearly defined sections, each of which is separately tracked. At the very start a lone trumpet plays a theme which will pervade the symphony (except in the second section). The contours of the theme and the fact that the trumpet is unaccompanied mean that the tonality is very hard to discern immediately; the tonality only becomes clearer as other instruments join in. The initial tempo marking is Allegro molto moderato and Moralt takes careful note of the ‘molto moderato’ part of that instruction. He unfolds the music spaciously, though by no means too slowly; he gives Schmidt’s melody, and all that flows from it, room to breathe. In fact, now is a good time to say that throughout the performance I found his tempo selections convincing and I also admired the flexibility that he adopts, where desirable, within a given tempo. He takes 14:57 to play this first section; of the versions I know, only Mehta (15:34) takes longer. Moralt’s overall timing is pretty close to the 14:27 of Paavo Järvi (review) whereas Kirill Petrenko (review) and Franz Welser-Möst in his 1994 EMI version with the LPO are swifter. I mention these other recordings simply to contextualise Moralt’s interpretation; as I said, I have no issues at all with his tempi.

In his valuable notes, Lani Spahr reminds us that the symphony’s second section (Adagio – Più lento – Adagio) was designated by Schmidt as ‘A Requiem for my daughter’. It’s surely not without significance that the elegiac principal theme is voiced firstly on Schmidt’s own instrument, the cello. The VSO’s cellist is a very fine player who delivers this extended solo with dignified eloquence. Again, in this section Moralt gives the music the time and space that it needs; it all seems very natural. This section is the heart of the symphony and it receives a fine, heartfelt performance. The third section (Molto vivace) is, in effect, the Scherzo. Moralt takes this at a sensible pace which invests the music with life and allows his orchestra to articulate the music crisply. The section is well done, although the effect of the brief cathartic climax close to the end is rather constrained by the recording. The trumpet’s motto theme has been in evidence during the Scherzo and it’s even more to the fore in the closing section which mirrors in many ways the opening part of the symphony. I think Moralt handles this last section very convincingly. Eventually, in the last couple of minutes, the solo trumpet returns to play his melody; he’s discreetly accompanied this time but eventually the accompaniment dies away and the trumpeter is left to play his last notes unaccompanied; that has always seemed to me to be a most satisfactory musical QED.

I think this is a very good performance. Moralt has the measure of the score and communicates it convincingly. The Vienna Symphony plays very well for him. Overall, Moralt’s timing of 47:06 is on the generous side: of the versions I know, only Mehta (49:02) is longer. Just for reference, Paavo Järvi’s version takes 44:34. Welser-Möst comes in at 43:36 and Petrenko seems to be the swiftest at 40:52. But the stopwatch can be a fallible guide; I’ve admired all of those versions in the past – and continue to do so. Moralt’s interpretation is worthy to stand beside them.

The recording does betray its age at times, most of all in the climaxes which do sound somewhat congested. Also, I suspect that the recording doesn’t flatter the tone of the VSO’s violins; in real life, I bet the edge which is sometimes in evidence when they play loudly was not a factor. The recording took place in a resonant acoustic, which blurs inner detail quite a bit (you can really experience the resonance at 11:02 into the first section, where there’s a general pause in which the music echoes). All that said, this seventy-year-old recording has come up very well in Lani Spahr’s restoration and I found that both through loudspeakers and headphones the sound is no impediment to enjoyment of the performance.

The oratorio Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln (The Book with Seven Seals) was an extremely ambitious undertaking, the composition of which occupied Schmidt between 1935 and 1937. The subject is a huge one: a musical setting, in German, of eight chapters from the Book of Revelation, in which St John tells of the Apocalypse. Everything is on a vast scale: the work is scored for no fewer than six vocal soloists, a large SATB choir, orchestra and organ; the latter instrument is not only an essential part of the accompaniment in many places but also has two solo movements. The length of the piece is substantial: this performance plays for 110:40, which is on a par with the three other recordings I know (by Dimitri Mitropoulos (1959), Franz Welser-Möst (1997), Kristian Järvi (2005)).

This recording, made in January 1962 in the Stefaniensaal in the Austrian city of Graz, was the first commercial recording of the work; it was issued on LP, and subsequently, I understand, on CD, by the Amadeo label. (An incandescent live recording, conducted by Dimitri Mitropoulos, of a performance at the 1959 Salzburg Festival was issued by Sony. However, according to my copy of the recording, it was published in 1995. So, as far as I’m aware, the present recording, made in stereo and, I understand, under studio conditions, justifies the ‘premiere recording’ tag.) The conductor, Anton Lippe (1905-1974) had quite a connection with the work, it seems. From what I’ve been able to learn of Lippe through some web research, he was the conductor of the choir of Graz Cathedral (1935-1964), after which he occupied a similar position at St Hedwig’s Cathedral, Berlin until his death. At some stage during his time in Graz I believe he began a tradition of annual performances of Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln. More than that, he had been a composition student of Schmidt at the Vienna Conservatory. So, too, was Julius Patzak (1898-1974), who sings the principal role of St John. I have a recollection of reading somewhere that the role of St John was one which he performed a lot. Perhaps doing so was, in part, a kind of homage to Schmidt, who taught him composition before his singing career began.

By the time of this performance Patzak was nearly 64 and he deserves great credit for being able to sustain such a substantial and demanding role. His voice could fairly be described as individual. A few years ago, I acquired a live recording of a German-language performance of Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius in which Patzak sang the title role. That was given two years earlier, in 1960. In my review, I noted a number of positive features of his performance but I also made this comment: “His tone is something of an acquired taste; it’s certainly nasal, one might call it pinched. To my ears some of his notes sound insufficiently supported and often there’s a definite tendency to sing notes on the flat side.” Here, the voice again strikes me as narrowly focussed and, yes, pinched. However, I’m happy to report that I detect no pitching problems this time. In fact, if you can ‘get past’ the tonal quality – and I think you should try to do so – Patzak sings with terrific clarity – his diction is crystal clear – and command. He gives a highly committed performance and seems tireless in his singing. True, I miss a degree of subtlety at times – I wish, for example, he had been more tender at the start of the passage in Part II where he describes the appearance of a woman about to give birth (‘Ein Weib, umkleidet mit der Sonne’ CD 2, tr 10) – but overall, his performance compels admiration; at all times his singing has the ring of conviction.

The other vocal soloists all make good contributions: Otto Wiener (1911-2000) is suitably imposing as the Voice of the Lord and his final majestic solo (‘Ich bin das A und das O’) is commandingly delivered. All six vocal soloists can be clearly heard and appreciated because they’re forwardly placed in the recording: I’m sure they were positioned in front of the orchestra, on a level with the conductor’s rostrum.

The Graz Cathedral Choir, Lippe’s own ensemble, sounds to be a large body of singers; I wonder if Graz Cathedral perhaps boasted a large choral society-like choir and a smaller body of singers for the services? The recording presents two issues as far as the choir is concerned. Firstly, they were recorded in a substantial and resonant acoustic and secondly, it sounds as if they were positioned – as one would expect – behind the orchestra. All this means that their sound is a little more recessed than one would ideally like (and more so than would be the case on a recording made nowadays). Furthermore, they aren’t helped by the fact that Schmidt’s contrapuntal choral writing is sometimes very dense – a prime example is the extended choral/orchestral depiction of the War in Heaven in Part II (CD 2, tr 11). But – and it’s an important ‘but’ – there is absolutely no denying the commitment with which they sing Schmidt’s often challenging music. If indeed Anton Lippe did perform Das Buch annually in Graz then most of his singers will have been familiar with the music; frankly, it shows. Even though I would have liked to hear them with even more clarity, it was evident to me that this was an accomplished, well-prepared choir, dedicated to the task in hand. Only once did they seriously disappoint: in the grandiose ‘Hallelujah’ chorus near the end of Part II, not all the sopranos successfully negotiate the extremely high notes that Schmidt expected them to sing fortissimo and in alt; the pitching of those high notes is, shall we say, somewhat democratic.

The Munich Philharmonic does a very good job for Lippe. Again, the recording – and the acoustic – muffles a lot of internal detail, especially in the louder passages. However, I noted, for example, the tension the orchestra generates in some of the passages where Schmidt conveys hushed awe. They offer exciting playing during the War in Heaven episode and there are many instances of delicate, refined playing. I must not omit to mention organist Franz Illenberger. The instrument he plays has quite a reedy sound – at least as recorded – but I don’t find this unsuitable. The organ can be heard quite well in the passages where it combines with the orchestra and in the two solo movements it comes into its own. The way Illenberger builds the first of these solos from a hushed start to the grand sound of the organ in pleno is very impressive.

The score is complex and as such constitutes a significant test for the conductor. It seemed to me that Anton Lippe has full command of the music and he directs a performance that is convincing on all fronts.

With the exception of Patzak, Otto Wiener and Hertha Töpper you may not recognise the names of many of the participants; other subsequent recordings have featured more stellar names. However, don’t be concerned; this is definitely not a provincial affair. This recording was made in 1962, since when standards of choral singing, orchestral playing and the engineering of recordings have all risen significantly. However, this is a performance – and recording – that significantly exceeded my expectations. As I listened, I had the distinct impression that everyone involved was completely committed to the cause. The recording may not be perfect; it is over sixty years old, after all. But the sound has come up very well in Lani Spahr’s skilled restoration and I didn’t find that the recorded sound inhibited my appreciation of the performance in any way.

SOMM haven’t included the text or translation in their booklet – there’s a QR code instead (which I haven’t used). I can understand why the label has done this; printing such a substantial libretto and translation would have added significantly to the size of the booklet and therefore to their costs. In any case, I doubt anyone will buy this set as their only recording of Das Buch. Rather, collectors are likely to acquire it as an archive set in addition to one of the modern recordings which include the libretto in their booklet; that’s how I followed the piece when playing the SOMM discs.

Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln isn’t to everyone’s taste. It’s a very long work, for one thing and there’s an argument, I think, that Part II is more dramatically and musically impressive than Part I. However, the oratorio contains a significant amount of fascinating music; at its best I think the term ‘visionary’ is not too strong. All admirers of Schmidt will want a modern recording in their collection in order to appreciate the score in optimum sound. Anyone who cares about the work should also try to hear the inspired Mitropoulos recording. However, I’m not sure that it’s currently available (though you might pick up a second-hand copy). But even if that version were readily available, I’d still encourage you to hear Anton Lippe’s fine performance.

With this 150th anniversary release, SOMM have done a signal service to Franz Schmidt in making available these two archive recordings in excellent transfers. Not only do both have a claim on our attention as the premiere recordings of the respective works; each of them is a fine achievement in their own right.

John Quinn

Previous review: Stephen Greenbank (May 2024)

If you purchase this recording using a link below, it generates revenue for MWI and helps us maintain free access to the site