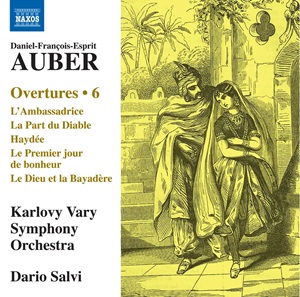

Daniel-François-Esprit Auber (1782-1871)

Overtures Vol 6

Karlovy Vary Symphony Orchestra / Dario Salvi

rec. 2022, Lidový dům, Stará Role, Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic

Naxos 8.574532 [87]

Anyone old enough to recall the 1960s will remember the ubiquity in those days of collections of lighter classical music on disc. New mass markets created by higher standards of living, along with the development of long-playing records, encouraged HMV, Decca, RCA and all the rest to churn out a seemingly endless supply of classical “pops”. Collections of mainly-19th century overtures proved especially popular, with tyro conductors using them to make their reputations and more established names wanting to be seen letting their hair down. A few of Auber’s works were regular features of such compilations, which is how many of us first made the acquaintance of the likes of La muette de Portici, Fra diavolo, Le cheval de bronze and Les diamants de la couronne.

This new volume in Naxos’s ongoing exploration of Auber’s operatic overtures and other orchestral music written for the stage leads us, though, into far less familiar territory. Auber Overtures 6 proves to be just as enterprising as the six previous discs in this ongoing series (volumes 1 to 5, plus a single oddly un-numbered entry, all but one conducted by Dario Salvi). The works on which it throws its spotlight are something of a mixed bag, composed at various points over nearly 40 years and, as Robert Ignatius Letellier’s usefully informative booklet notes make clear, addressing a typically eclectic range of subject matter. As well as five overtures that will probably be unfamiliar to most listeners, the disc includes three of those often quite substantial dance episodes that, at the demand of audiences, were frequently shoehorned – often entirely incongruously – into mid-19th century Parisian operatic productions.

In a musical era characterised by the rise of the cult of the star/virtuoso musical performer (Paganini, Liszt et al.), stories featuring celebrated artists are the focus of both L’ambassadrice and La part du diable. While the former, a great commercial success, centres on a fictional retired singer’s return to the stage, the latter depicts the real-life 18th century castrato Farinelli attempting to cure a king’s depression through the medium of song. Both operas are represented here by their overtures and the pair make a good contrast in displaying different facets of Auber’s compositional skill. While L’ambassadrice’s is a breezily jaunty little number, that to La part du diable is more memorable for its episodes of lyricism.

Auber’s Haydée takes us even further back in time, embellishing its 16th century setting of Adriatic politics and nautical derring-do with a love story that’s first complicated by, but ultimately transcends, differences in both race and social class. Its overture is, typically, something of an episodic pot-pourri, yet its engaging tunes make an effective introduction that would have settled audiences into their seats and put them in an appropriately receptive mood for the opera. It certainly fulfilled that aim, if we are to judge from the fact that Haydée (“one of Auber’s most significant and serious scores”, in the opinion of Mr Letellier) clocked up a remarkable tally of just shy of 500 Paris performances by the end of the 19th century.

Three other Auber compositions, Le premier jour de bonheur, Le dieu et la bayadère and La fiancée du roi de Garbe, are all set in Asia. They reflect – at least in their subject-matter – the 19th century’s growing fascination with that continent’s perceived exoticism. However, if you had expected non-European settings to introduce some novelty into the music, you would be rather disappointed. Experienced composers like Auber knew that the conservative audiences of the Second Empire wanted their entertainment delivered in a comfortable, conventional manner. In 1867 the writer and social commentator Charles Yriarte regretfully observed that “[t]he man of fashion at the Opéra… has a horror… of anything artistic, which must be listened to, respected, or requires an effort to be understood” (Ivor Guest The ballet of the Second Empire 1847-1858 [London, 1955], p. 14). Unlike their more adventurous children, who thrilled to gamelan orchestras and Cambodian music at the 1889 Paris World’s Fair or their grandchildren, who positively revelled in the radicalism iconoclasm of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in the years preceding the First World War, mid-19th century French audiences were conventional in their tastes in melody and orchestration and averse to artistic challenge. Consequently, the unfamiliarity of non-European locations was conveyed on stage primarily by means of sets, props and costumes rather than through musical innovation. Incidentally – but very significantly in the context of this particular review – we should note that when M. Yriarte went on to explain what his contemporaries did enjoy, he was adamant that “The man of fashion… wants [instead] the brisk and lively melodies of M. Auber…” (Guest op. cit.).

We ought not, then, to expect too much in the way of innovative colour in Auber’s scores for operas set in the East. That to Le premiere jour de bonheur’s story focuses, in any case, less on the indigenous population than on the actions and interactions of Westerner interlopers – in this case French army officers stationed in 18th century India. Indeed, its overture opens with a prolonged militaristic flourish that’s so lacking in any hint of local colour that the regiment might as well be on manoeuvres in Provence as in Pondicherry. That martial atmosphere is, indeed, sufficiently dominant as to almost overwhelm the somewhat clichéd, sinuously “oriental” theme that enjoys its brief moment in the sub-continental sun (1:39–2:40) but makes little in the way of an immediate or strong impression.

In similar fashion, the music to the ballet that forms the finale to Act 2 of La fiancée du roi de Garbe hardly attempts to introduce anything much beyond a Western pastiche version of local colour. Nevertheless, considered on its own terms it provides a few undeniably enjoyable moments. There’s a grandly declamatory opening episode that’s rather reminiscent of (though it actually precedes by several decades) the Grand pas de deux electrique from Pyotr Schenk’s three-Act ballet féerie Bluebeard, after which there’s a lot of music that could just as easily have been penned by, let’s say, Ludwig Minkus – which, if you’ve read my review of his biography, you’ll know is a pretty positive assessment. I would have imagined that this Act 2 finale would have very effectively fulfilled its theatrical purpose, bringing down the curtain with a flourish while stimulating the audience’s pleasurable anticipation of Act 3. The fact, however, that La fiancée du roi de Garbe actually enjoyed only 38 performances indicates, perhaps, the gap between my own sensibilities and those of M. Yriarte’s imaginary “man of fashion at the Opéra”.

The third of the “exotic” operas under consideration here – and the earliest-composed of the works included on this disc – is Le dieu et la bayadère. As well as its overture, we are presented with four dance numbers from its first and second Acts. Even though the opera has no European characters or elements in its story at all, the artistic constraints that we’ve already noted mean that you’d be hard put to guess that fact from these particular parts of its score. The lightly tripping overture, certainly, could have been accorded any virtually jolly title at all (the booklet notes concede regretfully, but accurately, that it “eschews any sense of drama”). The Act 1 Air de danse ‘Pas de châle’, the Act 2 Air de danse et scène ‘Danse de Fatmé’ et ‘Danse de Zoloé’ and the Act 2 Air de danse et scène ‘Danse de Zoloé’ are equally lacking in specific atmosphere. My favourite number is the Act 1 Ballet: Après le pas de châle, written more than 30 years after the rest of the original opera for a theatrical revival, although that may well be because I was already familiar with some of its musical themes, as recycled by Pierre Lacotte for his hugely enjoyable reconstruction of Auber’s ballet Marco Spada.

The oddest and most unexpected entry here is undoubtedly Don Juan, a nine-number ballet that Auber cobbled together from various Mozart compositions, adapting each to varying extents so as to create something suitable for dancing on stage during performances of Don Giovanni. Those compositions included the Symphony No 40, the Piano Sonata No 11 (which provides its familiar Turkish rondo as a lively finale) and, most substantially, the String Quartet No 15. The bizarrely interpolated ballet sequence – all 23-odd entirely anachronistic minutes of it – sees Auber, on this occasion, as less a composer than what we might instead regard as a compiler, but it nevertheless offers an interesting example of the sort of work that even a leading musician of the time might be expected to undertake in order to earn a living. [Readers with good memories may recall that conductor Dario Salvi has previously recorded Franz von Suppé’s own, somewhat more ambitious, Mozart “rewrite”, dating from a decade earlier.]

Having so far conducted the Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra Pardubice (8.574005 and 8.574006), the Moravian Philharmonic Orchestra (8.574007 and 8.574143) and the Janacek Philharmonic Orchestra (8.574335) in this ongoing series, on this occasion Mr Salvi has moved on to a fourth band – the Karlovy Vary Symphony Orchestra. I have no explanation for that sequence of musical chairs but can thankfully report that the latest artistic partnership delivers accounts of this generally unfamiliar music that are just as accomplished and idiomatic as their predecessors’. The winning performances are further enhanced by the exemplary recording quality that has been a hallmark of this series so far.

I am, however, obliged to make one final point. You may have been observant enough to notice that this CD boasts a length of no less than 87 minutes. I mentioned this to a couple of my fellow reviewers and, like me, neither of them had come across a disc of that length before. Unfortunately, however, it would appear that such long playing times can sometimes cause technical issues. MusicWeb’s editor-in-chief John Quinn has reminded me that when BIS released an 84 minutes long disc last year, the accompanying booklet warned purchasers that its length might cause some domestic CD players to have difficulty playing the final track. Thankfully, on that occasion John himself found the warning to be unfounded, but I have to report that both my own players – each less than three years old – proved unable to play this new Naxos disc at all. While its details came up accurately on their display screens, the automatic start mechanisms failed to kick in and it proved equally impossible to activate the disc by using the remote control handsets. Ultimately, I discovered that the CD would play on my DVD player and that was how I managed to listen to the performances. Of course, it may well be that this very generously filled new release won’t cause you any technical problems at all. But, however you manage to hear it, if you’ve appreciated this ongoing Auber series so far, you will certainly enjoy this new instalment.

Rob Maynard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site

Contents

L’ambassadrice (1836) – overture

La part du diable, or Carlo Broschi (1843) – overture

Haydée, or Le secret (1847) – overture

Don Juan (1866) – Act 2 divertissement *

La fiancée du roi de Garbe (1864) – Act 2 finale, ballet (allegro) *

Le premier jour de bonheur (1868) – overture

Le dieu et la bayadère, or La courtisane amoureuse (1830) – overture

Le dieu et la bayadère, or La courtisane amoureuse (1830) – Act 1, no. 5 Air de danse ‘Pas de châle’

Le dieu et la bayadère, or La courtisane amoureuse (1830) – Act 1, ballet Après le pas de châle *

Le dieu et la bayadère, or La courtisane amoureuse (1830) – Act 2, no. 10 Air de danse et scène ‘Danse de Fatmé’ et ‘Danse de Zoloé’ *

Le dieu et la bayadère, or La courtisane amoureuse (1830) – Act 2, no. 10bis Air de danse et scène ‘Danse de Zoloé’ *

*world premiere recording