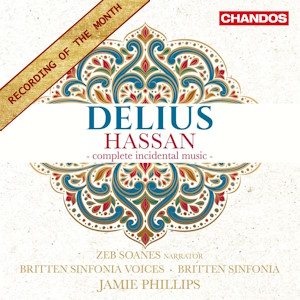

Frederick Delius (1862-1934)

Hassan (1920-1923)

Zeb Soanes (narrator)

Ruari Bowen (tenor)

Frederick Long (bass)

Britten Sinfonia Voices, Britten Sinfonia/Jamie Phillips

rec. live, 11 February 2023, Saffron Hall, Saffron Walden, UK

Chandos CHAN20296 [80]

James Elroy Flecker’s play Hassan must be one of the most extraordinary productions of the British stage in the twentieth century. Completed in the final months before the poet and playwright succumbed to tuberculosis in 1915 but not staged for another eight years, this massive work extends over five full-length acts (of two scenes apiece) and occupies nearly two hundred pages in print (in my 1922 first edition; a more recent paperback still runs to 140 pages). I doubt that it has ever been performed without cuts. When Basil Dean presented it to great public and critical success in London in 1923 with Delius’s incidental music, the text was trimmed to an extent that Dean later found it expedient to publish his own version reducing the play to three acts. The production was greeted with much enthusiasm but the play itself, presumably because of the considerable practical difficulties with presentation, has vanished from theatres. It is now stigmatised in many quarters as a sort of oriental pantomime with stereotypical characters drawn from fairy tales, or worse still as a distorted portrayal of genuine Islamic culture seen through the prejudiced eyes of a late British imperialist. (Flecker was a reluctant member of the diplomatic service.)

Both lines of attack have predictably already appeared in critical reviews of this new release; and both viewpoints are monstrously unjust and misguided. The oriental setting enabled Flecker to explore morbid elements of psychology. They would have been totally barred to him theatrically in any context closer to home – his visceral hatred of cruelty intertwined inextricably with an almost erotic fascination for the detailed mechanics of mental and physical torture. At the same time, his characters, even the ferocious and casually sadistic Caliph, are recognisable human characters. They can be understood by modern audiences – who through bitter experience have become all too familiar with the manner in which incredible inhumanities can be practiced by those who simultaneously profess a love of culture and civilised behaviour. Add to this a mixture of fatalistic pessimism (the lovers whose ghosts find that their pure and selfless devotion is no protection against the indifference of the world either in life or death) and the optimism of the pilgrims in the final scene who in vain seek to discover “why men were born”. It is easy to see, then, why the initially sceptical Delius was keen to write the incidental music for the first production, despite the rapid onset of the paralysis that was eventually to lead to his own death a decade later. In fact, the ailing composer had to seek the assistance of Percy Grainger to complete one section of the Act Two ballet. Grainger’s unexpected combination of two contrasting streams of musical thought strikes a quite un-Delian note which nevertheless seems to fit.

The nature of the play drew from Delius a score which contains some other unexpected elements. Apart from the extended sections of melodrama with speech declaimed over music (a subject to which I will return) there are also some quite startlingly jaunty passages for the beggars in Act Two, and even more for the War Song of the Saracens in Act Three. The latter, magnificently blood-curdling and sabre-rattling in a manner that is totally unlike anything else in the composer’s entire output, is however clearly intended to be treated in a satirical fashion. The text as set cuts two of the three verses from the original play, and Delius allows the music to die down after the final choral outburst into a muttering echo which is clearly intended to underscore the sneering remarks of the chief of police: “That is a splendid song your soldiers sing, O breaker of infidel bones. Permit an unglorious policeman to inquire what flaming victory you celebrate today. Such is my loathly ignorance, I knew not the Caliph’s army (may it ever plosh in seas of hostile blood!) had even left Bagdad.”

This quotation also underlines the frequently subversive nature of Flecker’s dialogue. Its subtle ironies are derived from the model of Wilde, which provides elements of contrast for Delius to exploit. The diverse nature of his score indeed seems to have militated against later performances. For many years, the only item of substance from the music which was regularly heard was the ubiquitous Serenade. It was originally written to underscore Hassan’s recitation in Act One but rapidly established as a small salon piece in its own right. Its versions featured viola solo (as in the original), violin solo and even wordless tenor voice, and a later appearance in the score for full orchestra after Hassan is reconciled with his faithless Yasmin. When I say full orchestra, this requires qualification. Delius complained bitterly that he was restricted to a chamber band of twenty-six players (only twenty-four in this recording). When Beecham came to record substantial excerpts from the incidental music in the 1950s, he expanded the string section considerably. At the same time, he pruned several sections of the score, eliminating not only much melodrama but other purely orchestral sections including Grainger’s contribution to the ballet. Indeed, the first time we were able to hear the complete incidental music on disc did not arrive until Vernon Handley’s performance with the Bournemouth Sinfonietta on EMI in 1979. Until this issue (as far as I can ascertain), amazingly nobody else has since attempted to get to grips with the work as a whole.

Handley’s version was valuable in its day, but it suffered from some quite severe drawbacks. Although it was recorded in the resonant acoustic of the Southampton Guildhall, the positioning of the microphones relatively close to the instrumentalists tended to decrease the ambience around the players. The strings in particularly often sounded underweight and the balance tended to favour the brass unduly, doing no favours to Delius’s delicately balanced scoring. And no attempt was made to supply the spoken voices. Delius clearly expected them to be heard over such passages as Ishak’s poem to the dawn or the voices of the various protagonists in the closing scene, with the orchestral backing heard in exposed isolation. This lack of the dramatic dimension may have led Handley into being somewhat brisk with some passages in the score. The closing scene seems to progress rather over-relentlessly towards its conclusion. The War Song is delivered at such lightning speed that the chorus have difficulty in getting the rhythms across (and there certainly would not be time available for the chief of police to deliver his acerbic comments already quoted over the final bars). No, there was clearly room for a new recording of the score, and this issue in many ways addresses some (but not all) of the problems.

In the first place, the recording quality is a considerable improvement on the EMI performance of nearly half a century ago. A warmer sound provides a more authentically Delian atmosphere to surround the players, and a more relaxed and flexible approach from Jamie Phillips. A serious attempt has also been made to come to terms with the dramatic elements that play such an important consideration in the score. Zeb Soanes is one of those speakers who seem to have an instinctive relationship to music (although I am sure that the results are also the consequence of careful study). Here, recorded live in the same acoustic as the orchestra, the balance between voice and instruments is ideally judged. Meurig Bowen provided a text, partially quoting from Flecker’s original or summarising the plot between items. This gives us much of what is wanted, including the assumption by Soanes of the character of Ishak for his poem about the dawn. And this is beautifully timed to fit the music, showing precisely with what care Delius matched the words to the inflections of the accompaniment. But elsewhere Bowen’s text shows equal care to avoid this conjunction of words and music, as in Hassan’s serenade or the final scene.

Clearly this results from concern that the music should be allowed to stand alone and not be obscured by the spoken voice, and this is a perfectly defensible position. But there are places, such as the final scene, where Delius’s score specifically instructs that some bars should be repeated if necessary to allow room for the speakers. The passages in question indisputably work better if the words are in place. “We travel not for trafficking alone”, declares Ishak. Without his philosophical explanation for the pilgrimage the listener is left with only the picturesque elements in the story. The sinuous counterpoint of flutes and solo violin at this point is exquisite; but they are also intended to be illustrative of the “lust of knowing what should not be known”.

There is one other element in this new performance which could perhaps have been improved, and that is the size of the chorus. Delius may have been compelled to compromise with a smaller orchestra than usual. Yet he clearly expected a substantial body of sound from his singers not only in their offstage chanting but in their dramatic function. His intentions regarding scale are demonstrated by how he divides his tenors into three parts in places; here, with just four tenors in the whole choral body, the effect is inevitably compromised. Handley, to judge by the sound of his recording, had a much larger number of singers to hand, and benefited in consequence. He also had better vocal soloists; the leader of the beggars, here delivered with dramatic relish rather than vocal polish, requires a solid sustained high F sharp from the singer. It does not get that here from Frederick Long with the firmness which Bryan Rayner Cook displayed on the EMI issue.

The tenor in this new recording, Ruari Bowen, has greater suavity and a more beautiful sense of distance than Martyn Hill for Handley, But his deliberate alteration of each of Delius’s three precisely-notated breathing indications in the final scene do not work to the advantage of the musical phrases. Handley also adds the vocal version of the Serenade, with Hill‘s rather smoother voice. This is omitted here, albeit with some justification since it finds no very obvious place in the dramatic scheme of the play and was not included in the published version of the score. This disc clearly contains as much of the material as could be accommodated within its very capacious length. The recording is said to be live, taken from a single performance. The audience is astonishingly silent throughout, and pauses between tracks are minimal.

The new recording is very good in matters of balance, given the difficulties of combination of spoken voice and orchestra with onstage and offstage chorus. I would question the rather distant balance of the percussion. The xylophone in the March of protracted death, explosively ebullient in Beecham, is hardly audible here, and the onstage camel bells in the final scene are almost totally smothered by the quiet playing of the rest of the orchestra. But the end of the score, as the voices and orchestra fade into almost total inaudibility as the pilgrimage recedes into the distance, is judged to perfection in exactly the manner specified in the score. It is amazing to learn that in the first German production of Hassan (which preceded that in London by a couple of months) this scene was actually cut. I do recall a BBC radio production of the play back in 1973 which brought the work off rather well. Rob Barnett reviewing the Handley recording issued as part of EMI’s ‘Delius box’ in 2012 entered a plea for this to be issued on disc. Even better, as I recall, was an Irish radio version in the late 1960s (with a narration by Michéal Mac Liammóir) ruined only by some intrusive electronic sound effects. If RTÉ still have copies of that tape, edited excerpts would be welcome. I once had a cassette copy myself which I gave to Mac Liammóir in 1971, and which might still be found in his archives. There certainly remains room for alternative versions of this work which experiment with various solutions to the intended results.

In the meantime, however, let us welcome this new recording of Hassan. It must most certainly be hailed as the best version yet available on disc, and it hopefully should convert new listeners to the merits of the score. The booklet is ideal, with essays in English, French and German, and the complete text including the narration in English. The tracking is generous, with fifty independent points of access.

And I will conclude – yet again! – with a plea for the reissue of the BBC Artium recordings conducted by Norman Del Mar of the early Delius operas Irmelin, The Magic Fountain and Margot le Rouge. They have been unavailable for many years now and second-hand CDs – if available at all – are only to be procured at exorbitant cost. I have been plugging away for over ten years now on this scandalous situation, and I am not about to give up now.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.