Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

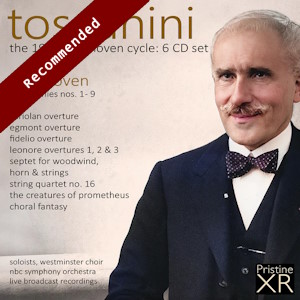

Toscanini: The 1939 Beethoven Cycle

Symphonies 1-9 & other works

NBC Symphony Orchestra/Arturo Toscanini

rec. live broadcasts, 28 October, 4, 11, 18, and 25 November, 2 December 1939, NBC Studio 8H, Radio City, New York

Pristine Audio PABX023 [6 CDs: 477]

Arturo Toscanini’s (1939) recordings of Ludwig van Beethoven’s nine ‘canonical’ symphonies, plus a number of overtures and orchestral arrangements of chamber works, have been issued multiple times. Their latest incarnation on Pristine Audio (2023), which utilises XR remastering, makes these recordings competitive with subsequent ones by revealing an astonishing amount of musical detail with little audible background noise and distortion. Pristine Audio remedies, to a degree, the notoriously ‘dry’, ‘cramped’ acoustic of Studio 8H, where so many of Toscanini’s recordings had the misfortune to be made. Furthermore, Pristine includes the full broadcasts with the presenter’s commentary and the audience’s applause (embarrassingly, between movements in the sixth symphony!).

Even with multitudinous Beethoven cycles available, including some based on the latest philological research, Toscanini’s interpretations remain compelling because each of the symphonies emerges as thoroughly convincing. Toscanini inspired the NBC Symphony to reach his extraordinarily high standard in these unedited live broadcasts. The only deficiency is the omission of some of the exposition repeats (e.g., in the Third and Seventh Symphonies), but he observed them in the First, Second, Fourth, and Sixth Symphonies. Neither the choir nor the soloists in the final movement of the Ninth Symphony are among my favourites: Ferenc Fricsay (1958) and Herbert von Karajan (1962) reign supreme in this movement. Other cycles, including those by Otto Klemperer, Wilhelm Furtwängler, and Karajan, have their overt weaknesses. Klemperer succeeded with the Second, Fourth, and Sixth Symphonies; Furtwängler’s greatest Beethoven recordings were of the Ninth in Bayreuth (1951) and Luzern (1954). Released in 1963, Karajan’s cycle, the first to be conceived and released as such, remains the most satisfying overall, but the Sixth, as many commentators have noted, does not sound ‘pastoral’ (Karl Böhm’s Sixth from 1971, which is arguably the finest on record, makes an ideal supplement).

The greatest challenge with analysing Toscanini’s recordings is understanding how he elicited an unparalleled degree of passion. Although Toscanini performed Beethoven faster than was customary at the time, it is not mere speed that makes these performances so engrossing. For example, I saw Riccardo Chailly conduct some of the Beethoven symphonies at the Gewandhaus in Leipzig at swifter tempi than Toscanini’s. Even with a superior orchestra at his disposal, Chailly did not match Toscanini’s forward momentum, lyricism, eloquence, or emotional depth (Decca’s recordings support my judgement). Toscanini articulated the symphonies’ form and texture to unfold their inherent drama: pianissimi are graceful, and forti seem overwhelming. The opening movements of the Third and Fifth Symphonies are searingly intense; the outer movements of the Seventh Symphony are infernal; the development section of the opening ‘Allegro vivace e con brio’ to the Eighth Symphony is thrilling). The ‘Marcia funebre (Adagio assai)’ in the Third Symphony is more profound and riveting than readings by Klemperer and Fürtwängler because Toscanini’s lithe phrasing better expresses solemnity. The latter conductors undermined this movement’s impact with dramatically eviscerated interpretations of the opening ‘Allegro con brio’ that provide less contrast.

Toscanini refined his then-radical interpretations of Beethoven’s symphonies by putting them into practice over many decades. Unlike conductors born after the turn of the twentieth century, Toscanini did not have access to recordings by other musicians. When the gramophone industry began disseminating music, he was already in his 40s and well established as a conductor. He developed his own view by studying Beethoven’s scores, which he refused to embellish with personal additions or changes, and working through his readings with orchestras he convinced to follow his vision. Tempi flow without ever feeling rushed, even when they are among the fastest on record (the first movement of the Ninth Symphony is less than 12:30). Subsequent generations of conductors, including those who seek to avoid performing traditions (i.e., by using period instruments and Urtexts), have been influenced by Toscanini and other legends (e.g., Felix Weingartner, Bruno Walter, and Furtwängler). Finding a unique personal voice today has become difficult because recordings impact musicians’ and audiences’ ideas of how music should sound.

Daniel Floyd

Availability: Pristine Classical

Contents

Symphony No. 1 in C major, op. 21 (1800)

Symphony No. 2 in D major, op. 36 (1802)

Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, op. 55 (1803)

Symphony No. 4 in B-flat major, op. 60 (1806)

Symphony No. 5 in C minor, op. 67 (1808)

Symphony No. 6 in F major, op. 68 (1808)

Symphony No. 7 in A major, op. 92 (1812)

Symphony No. 8 in F major, op. 93 (1812)

Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op. 125 (1824)

Overtures: Leonore No. 1, op. 138 (1805), Leonore No. 2, op. 72a (1805), Leonore No. 3, op. 72b (1805), Fidelio, op. 72 (1814), Coriolan, op. 62 (1807), Egmont, op. 84 (1810)

Creatures of Prometheus, op. 43 [No. 5: ‘Adagio – Andante quasi Allegretto’] (1801)

Choral Fantasy in C minor, op. 80 (1809)

Septet in E-flat major, op. 20 (1800)

String Quartet No. 16 in F major, op. 135 [No. 3: ‘Assai lento, cantante e tranquillo’, No. 2: ‘Vivace’] (1828)