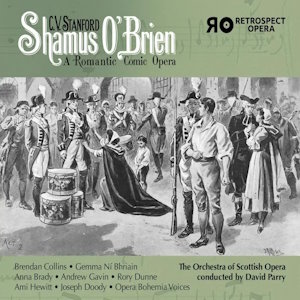

Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924)

Shamus O’Brien, Op 61 (1896)

A Romantic Comic Opera

Shamus O’Brien – Brendan Collins (baritone)

Nora O’Brien – Gemma Ni Bhriain (mezzo-soprano) / Anna Brady (dialogue)

Mike Murphy – Andrew Gavin (tenor)|

Father O’Flynn – Rory Dunne (bass-baritone)

Kitty, Nora’s sister – Ami Hewitt (soprano)

Captain Trevor – Joseph Doody (tenor)

Opera Bohemia Voices

Orchestra of Scottish Opera/David Parry

rec. 2023, Silver Cloud Studios, Glasgow and Champs Hill, Surrey

Text included

Retrospect Opera RO011 [2 CDs: 138]

In the year that we mark the centenary of the death of Charles Villiers Stanford, the ever-enterprising Retrospect Opera label has put admirers of the composer in their debt by issuing the first complete recording of the fourth of his nine operas, the comic opera, Shamus O’Brien. I think I’m right in saying that this is only the second complete recording of a Stanford opera: his final opera, The Travelling Companion Op 146 (1916), was released by SOMM Recordings back in 2019 (review). When The Travelling Companion appeared on disc it was a recording of a live December 2018 performance given by New Sussex Opera; this premiere recording of Shamus O’Brien was made under studio conditions.

Retrospect Opera has not stinted in the matter of documentation. The booklet contains no fewer than four essays. Two, about the work itself, are by the Stanford experts Jeremy Dibble and Paul Rodmell. There’s also a contribution from Adèle Commins on the topic of Irish piping; last, but by no means least, there’s an essay by Rory Dunne (who sings the part of Fr O’Flynn), giving an Irish perspective on the opera. I gratefully acknowledge all four authors; on whose writings I have drawn, to varying degrees, to sketch in the background to Shamus O’Brien .

Jeremy Dibble reminds us that a goodly amount of Stanford’s works had already exhibited explicit Irish influences before he wrote Shamus O’Brien. Citing the baritone, Harry Plunket Greene (1865-1936), Dibble states that the opera was very much Stanford’s idea; in fact, as he outlines in more detail in his comprehensive biography of the composer, Charles Villiers Stanford, Man and Musician (2002), the idea had been gestating since at least 1891. Stanford was inspired by the poem, Shamus O’Brien by the Irish writer Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873). Stanford enrolled a fellow-Irishman, George Henry Jessop (1852-1915) as his librettist. The background to Le Fanu’s poem and, therefore, Stanford’s opera was the 1798 Irish Rebellion and Dibble draws attention in the booklet to the timing of Stanford’s venture: Irish affairs had been very prominent in a number of ways in late nineteenth-century Britain, not least on account of widespread disappointment within Ireland over Gladstone’s Home Rule Bill of 1885. It seems that the composition of the opera proceeded swiftly. In his biography of Stanford, Jeremy Dibble mentions that Act I was finished over Christmas 1894 while Act II and the overture were completed before the end of the following January.

When the opera began a run of nearly three months in London in March 1896, Stanford had managed to secure the services of Henry Wood, no less, to conduct (and Stanford’s pupil, Gustav Holst was a member of the trombone section). It seems that the work impressed Wood. After the London run, the opera was toured in the UK, including performances in several Irish cities; though Wood was unavailable, Granville Bantock conducted some of the touring performances in England. There followed a run of performances in New York and Chicago in 1897 before a second UK provincial tour. So, Shamus O’Brien enjoyed initial success; indeed, in his aforementioned Stanford biography, Dibble uses the term “massive success”. There was clearly a degree of critical hyperbole at the time; Dibble quotes one 1897 critic who described the opera as “the Freischütz of a new school of British opera”. In his booklet essay, Dibble relates that Stanford refused to sanction further performances after 1910, fearing that the subject matter was inappropriate in view of rising political tensions in Ireland. After the composer’s death there were a number of performances in the 1920s and 1930s but Shamus O’Brien fell into complete neglect during and after World War II.

At this point, having mentioned Stanford’s concerns over political sensitivities, it’s appropriate to summarise the plot, as detailed in the helpful synopsis which is printed in the booklet. The action takes place in the Irish village of Ballyhamis (in the Cork mountains) soon after the 1798 Irish Rebellion had been suppressed by the British. Shamus O’Brien is on the run from the British military. A peasant farmer, Mike Murphy has informed on him in revenge for, in his eyes, stealing from him Nora, who preferred Shamus to Murphy and became the former’s wife. Kitty, Nora’s sister, overhears Murphy talking with Captain Trevor of the British Army. She warns Shamus that he is to be ambushed. With the help of the local priest, Father O’Flynn, Shamus disguises himself as the village idiot, Thady Farrell and deceives the British into believing that he, Farrell, can lead them to Shamus. Our hero returns to the village after hoodwinking Trevor and his soldiers, whereupon he is seized by Murphy. In Act II, Shamus is tried by a military tribunal and sentenced to hang. Father O’Flynn accompanies Shamus in the cart taking him to the place of execution. The priest cuts Shamus free, enabling him to make his escape. The British soldiers try to shoot him as he flees, but they miss and kill Murphy instead.

Paul Rodmell points out that in his three previous operas, Stanford had embraced the grand opera tradition; consequently, Shamus O’Brien, which was, essentially, an opéra comique, was a new departure. Rodmell, who notes the “insatiable appetite” of British audiences of the day for light opera and operetta, asserts that Shamus O’Brien “sits comfortably in neither the ‘serious’ opera category nor that of ‘light opera’ but rather in the middle ground of opéra comique”. He goes on to say that the work “stands out…because of its dramatic themes and structure: its scenario combines comic, serious and romantic elements in roughly equal proportions, its musical numbers are separated by sections of spoken dialogue, and the music aims at a tunefulness and lyricism akin to light opera while employing more complex and nuanced musical structure associated with recent grand operas which respond to the libretto’s twists and turns”. It’s worth noting that despite the opera’s Irish subject, only two folk songs are employed – and only one of these is Irish! That said, Rodmell observes that “Stanford’s familiarity with Irish folk music…enabled him to imitate its melodic contours and rhythms in a manner as deft as one finds in Dvořák’s music”. At one point in Act I (CD 1, tr 16), Stanford emphasised the Irish nature of the music by including a prominent part for the uilleann pipes, also known as Irish or union pipes. Adèle Commins tells us that this traditional instrument dates back to the 1740s.

I think it’s important for listeners to read Rory Dunne’s short essay in which he points out elements of the libretto that strike a discordant note today, reflecting some of the attitudes of the Anglo-Irish Establishment in the late nineteenth century. Dunne’s is a balanced view, I think; he discusses the shortcomings but also acknowledges that despite these Shamus O’Brien “continues to excel musically and as an entertainment”.

I’ve summarised – very briefly – what seem to me the key points from the documentation because Shamus O’Brien is likely to be unknown to most of our readers. It’s now high time to consider the opera itself and the performance it receives.

I have to say that Shamus O’Brien strikes me as something of a mixed bag. The orchestral writing is a consistent source of pleasure; the scoring, which is often light and airy, is clearly the work of a composer with a fine feel for orchestration; the accompaniment constantly offers attractive colouring which complements the singers’ music very well indeed. The vocal writing, both solo and choral, is similarly assured and Stanford’s skill – plus the excellent diction of everyone involved in this performance – means that the words always register clearly. The music is unfailingly melodious and attractive – the Overture is an early example of what lies in store. There are less successful features, though. Viewed from a twenty-first-century perspective, the libretto could fairly be described as ‘of its time’. I also think that there are times, particularly in Act I, where the light, cheery nature of Stanford’s music is somewhat at odds with what is being expressed in the words. For example, right at the start of Act I the Chorus reference, fairly briefly, the terrible aftermath of the unsuccessful rebellion. ‘It’s bitter news. It’s wicked news’, they sing: the trouble is, they do so to music that sounds far too up-beat and lively. Act I is often too light in tone for its subject matter and, to my ears at least, lacks sufficient drama; things are a bit too genial and homely. I should say at once that as the opera moves to its dénouement in Act II the drama is portrayed rather more convincingly; if only Act I had been stronger in tone.

Jeremy Dibble says that the work is “an unequivocal ‘number’ opera”; often the passages between one musical item and another involve spoken dialogue. (I gather that, in the hope of making Shamus O’Brien appealing to continental opera houses, Stanford tried to make it into a ‘grand opera’ by transforming the sections of dialogue into recitative. Henry Wood, for one, thought this was a mistake.) Here, the dialogue is mainly spoken by the cast. I say “mainly” because Anna Brady, rather than Gemma Ni Bhriain, speaks Nora’s dialogue lines; also, I’m guessing that the entirely spoken role of Sergeant Cox is taken by the conductor, David Parry. For the most part the dialogue is well done and nicely paced. However, I have a major reservation about the way Joseph Doody speaks Captain Trevor’s lines. Seeking to portray the captain as very English and to differentiate him from all the Irish characters, Doody makes Trevor sound like a caricature of a young English toff; the effect is far too overdone. (I have no reservations, though, about the way in which Doody sings the part of Trevor.)

Despite the excellence of the performance, the work itself didn’t really engage me at first; it struck me as too genial. Kitty, Nora’s sister, has a rather touching little song (‘Where is the man that is comin’ to marry me?’), which Ami Hewitt sings nicely (CD1, tr 5). A little later, soon after his first appearance on the scene, Shamus has a manly, resolute solo (‘I’ve sharpened the sword for the sake of Ould Erin’); this is our first opportunity to admire the firm, pleasing baritone of Brendan Collins (tr 11). The ensemble that follows, involving Shamus, Nora, Kitty and Father O’Flynn is handled with assurance by Stanford, though I’m not bowled over by the words he sets. However, things start to improve significantly in the extensive finale (which lasts for over 20 minutes). There’s an aria for Nora ((tr 15) in which she sings of her apprehension at hearing the haunting (offstage) sound of The Banshee. Here the music is darker, yet still lyrical, and the melodic material is excellent. Gemma Ni Bhriain sings this number really well – and with no little feeling. The big ensemble piece which follows, lasting over 13 minutes (tr 16) is very well constructed by Stanford and contains some good music; Shamus’s song of farewell to Nora (‘Darlin’, adieu to you!’) has a noble melody. During this extended ensemble, the duplicitous Mike Murphy ensures the capture of Shamus. After what struck me as a dramatically uncertain start, it seems to me that Stanford really hit his straps in the last twenty minutes or so of Act I.

For the most part, Act II picks up where Act I left off. Just as the Overture was delightful, so too is the Entr’acte; this bridge to Act II includes some particularly felicitous writing for the woodwind section. Captain Trevor has fallen for Kitty (who uses this to twist him round her little finger). He’s on the horns of a huge dilemma; his sense of duty means he can’t let Shamus go, but he knows Kitty will never forgive him if he doesn’t. He laments the position he’s in during an attractive, romantic number (’My heart is thrall to Kitty’s beauty’). Joseph Doody sings this really well, his voice clear and ringing (CD 2, tr 3). Trevor determines to convene a drumhead court-martial, though he faces a problem in that Murphy hasn’t yet received the promised reward for delivering up Shamus and is pressing for what he believes is due to him. The discussion between them is partly spoken but also includes a sung duet in which we hear two good, light lyric tenors, Doody and Andrew Gavin. I wondered, though, if the music they sing, fluent and appealing though it is, is a bit too light in character for the sentiments that are being expressed. The other thought that crossed my mind – and not for the first time – was to question why Stanford had written the part of the dastardly Murphy for a tenor; might not a lower voce have better demonstrated his malevolence? Having said that, not long afterwards Murphy has a ballad-style number (‘Ochone, when I used to be young’), which Andrew Gavin sings very well. I think this song vindicates Stanford’s choice of the tenor voice for the character (tr 7).

As the action moves forward, Kitty entreats Trevor to allow Nora to visit Shamus in prison; there’s a charming duet between them (‘So its kisses you are cravin’’) in which, as Trevor believes, the deal is sealed (tr 10). Nora gets her visit. Strong feelings are expressed by Nora and Shamus during the prison visit (tr 12). Then the court martial takes place; it’s entirely conducted through spoken dialogue (tr 15). Inevitably, Shamus is found guilty, not least because he refuses to deny his participation in the Rebellion. He is sentenced to hang. Scene 1 of this Act concludes with an impassioned plea for clemency by Nora (‘Have mercy, your honour’), seconded by the Chorus, but it’s all to no avail. A melancholy Entr’acte leads to the second and final scene. There’s a well-worked trio for Kitty, Nora and Father O’Flynn (tr 18); here, Stanford’s music illustrates real feeling. As was the case in Act I, Stanford’s Finale to the second Act is a strong conclusion (tr 20). Nora and Kitty are full of emotion as Shamus’s procession to the gallows approaches. Shamus himself is portrayed as an heroic character; having refused to deny his part in the Rebellion during the trial, his thoughts as his execution approaches are focused on Nora. He delivers a defiant speech before his execution (‘Listen to me, men; I’ll be shortly goin’ …’). Brendan Collins sings this gallantly. Then, with time running out, Father O’Flynn seizes the opportunity to cut our hero free and he makes his escape; Murphy is fatally shot by mistake as the soldiers try to stop Shamus. Stanford and his librettist bring the opera to a very swift conclusion once Shamus is out of sight and free.

Stanford and Jessop tell an essentially straightforward tale in which the hero triumphs. As I said, I think the opera is something of a mixed bag but at its best it’s well worth hearing, not least to expand our knowledge of Stanford. I’ve now heard two of his nine operas and based on that limited sample I’d say he’s much more convincing as a composer of concert and liturgical music. That said, Shamus O’Brien is expertly crafted by the composer. I think he knew exactly what his audiences would want to hear and the strong success of the opera in the years immediately after its first performance suggests that his judgement was spot on.

If I have reservations about the work itself, I have no reservations about the performance. I think I’m right in saying that the principals are all Irish. All of them do very well; the singing is excellent, as is the diction. The members of Opera Bohemia Voices inject vitality into the music for the Chorus; they make a strong contribution. The Orchestra of Scottish Opera plays really well; there’s energy when called for and, in the more delicate episodes. a good deal of finesse in their playing. The musicians show Stanford’s fine writing for the orchestra to the best possible advantage. David Parry conducts a sparkling performance – when he’s not doubling up as a down-to-earth army sergeant.

The recording itself has been engineered by Dave Rowell. He and producer Alexander van Ingen have done a first-rate job; the sound is direct and clear. As I’ve already said, the documentation is exemplary.

I don’t think Retrospect Opera have unearthed an unjustly neglected masterpiece here. What they have done, though, is to allow us the rare opportunity to experience Stanford as a man of the theatre. That was an important aspect of his life’s work and, as I said, hearing his operas fills out our knowledge of him in a significant way. If you’re going to present the first recording of a neglected work you need to present it in the best possible light and through this excellent performance Retrospect Opera have done just that.

Help us financially by purchasing from

Other cast

The Banshee – Catriona Clark (soprano)

Sergeant Cox – David Parry (spoken role)

Jarlath Henderson (Irish piper)