Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904)

Complete Works for Violin and Orchestra

Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53

Romance in F minor for violin & orchestra, Op. 11

Mazurek in E minor for violin & orchestra, Op. 49

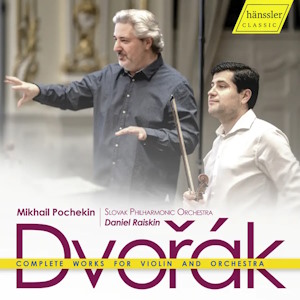

Mikhail Pochekin (violin)

Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra/Daniel Raiskin

rec. 2023, Konzertsaal, Slowakische Philharmonie, Bratislava, Slovakia

Hänssler Classic HC23057 [50]

In terms of popularity, Dvořák’s violin concerto and piano concerto are both eclipsed by the fame of his cello concerto, a jewel in the crown. Nevertheless, the violin concerto is still a work that merits being heard much more often.

By 1879, Dvořák was increasingly receiving international accolades and honours. That year he commenced writing his violin concerto and consulted his friend the famous virtuoso violinist Joseph Joachim. A composer himself, Joachim suggested several changes to the score, but his response was protracted; he took two years to reply. Dvořák did make Joachim’s alterations, but due to those delays the concerto wasn’t published by Simrock until 1883 when it received its premiere in Prague, not by Joachim but by František Ondříček.

Violin soloist on this album Mikhail Pochekin states how he admires the concerto’s Slavic style. The core of the work’s character is marked by traditional Bohemia folklore, melodies, dance and the people and places that influenced Dvořák.

Marked Allegro ma non troppo, the first movement opens impressively with its bold, noble orchestral announcement. Pochekin relishes the warm rhapsodic character of the writing playing with a deep intensity. Following without a break, the lyrical middle movement, Adagio ma non troppo, is notable for beautiful playing, dreamy, aching and gleaming. His spirited playing intensifies the Bohemia dance rhythms that punctuate the Finale, Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo and he creates a hugely impressive sense of optimism.

This release includes two shorter, single-movement works for violin and orchestra: the Romance in F minor and the Mazurek in E minor. Both are splendid works that don’t deserve their relative neglect. Dvořák based the Romance for violin and small orchestra on the main theme of the slow movement from his own String Quartet No. 5, Op. 19 (1873). It was theatre orchestra, concertmaster Josef Markus who premiered the Romance at Prague in 1879. Playing with ample spirit, Pochekin plays with spirit and clearly sees the captivating Romance as a type of poem containing folksong-like melodies capped by a stirring climax.

Following the remarkable success of Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances, Op. 46 in 1879 his publisher Simrock wanted another work of a ‘Slavonic’ character. In response Dvořák provided Simrock with a Mazurek (Mazurka) in E minor for violin and piano, that he soon orchestrated for violin and strings. Dedicated to the violin virtuoso Pablo de Sarasate, the Mazurek contains Bohemian folk melodies and rhythms that the talented Pochekin delights in and takes in his stride.

Pochekin is naturally attuned to the moods of each movement and able highly expressive. He plays an attractively toned violin by Neapolitan luthier Gennaro Gagliano (1762). The Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Daniel Raiskin provides sterling support; the relationship between them and Pochekin is clearly a meeting of minds.

Recording engineer Christian Starke provides Pochekin with first class sound. The booklet notes do not contain an essay; in its place is the text of an interview that music writer Dr. Burkhard Schäfer held with soloist Pochekin.

There are several fine recordings of Dvořák’s Violin Concerto including the 1989 Philadelphia account played by Kyung Wha Chung under Riccardo Muti for EMI, and also Maxim Vengerov under Kurt Masur from 1997 at New York City on Teldec. My standout account is by Anne-Sophie Mutter with the Berlin Philharmonic under Manfred Honeck, recorded in the Philharmonie, Berlin on Deutsche Grammophon (review). Mutter couples the Concerto with both the Romance, Op. 11 and Mazurek, Op. 49 plus the short Humoresque, Op. 101/7 in Fritz Kreisler’s arrangement for violin and piano. My CD contained a bonus DVD of Mutter’s live performances of the Violin Concerto and Romance. That recording is now up against a strong rival in Mikhail Pochekin and the choice is tricky. Her account of ravishing colour sounds more stylish than Pochekin whose compelling Bratislava recording benefits from an elevated level of Slavonic character and rhythmic verve.

Michael Cookson

Help us financially by purchasing from