Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Symphony No 2 in B major, Op 14 ‘To October’ (1927)

Symphony No 3 in E-flat major, Op 20 ‘The First of May’ (1929)

Symphony No. 12 in D minor, Op 112 ‘The Year 1917’ (1961)

Symphony No. 13 in B-flat minor, Op 113, ‘Babi Yar’ (1962)

Matthias Goerne (bass-baritone)

Tanglewood Festival Chorus & New England Conservatory Symphonic Choir

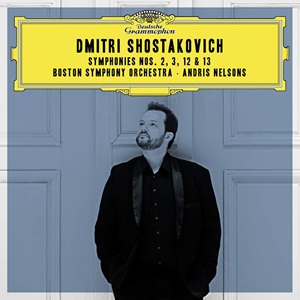

Boston Symphony Orchestra/Andris Nelsons

rec. live 2019 – 2023, Symphony Hall, Boston

Reviewed as a 24/96 press download

PDF booklet includes sung texts (transliterated Russian and English)

Deutsche Grammophon 486 4965 [3 CDs: 166]

And here it is, the final instalment of Andris Nelsons’ Boston Shostakovich cycle. Launched in 2015 with a solid account of Symphony No 10 (review), subsequent issues have varied between good and very good; indeed, the one comprising Nos 4 and 11 among my top picks for 2018 (review). Factor in exemplary engineering from the orchestra’s in-house team and it’s not hard to see why these recordings are such a welcome addition to the catalogue. No doubt DG will repackage them as a boxset just in time for the Shostakovich anniversary in 2025.

While none of the established sets is without flaw, the better ones all bring something important to the table. Kirill Kondrashin’s pioneering Melodiya series not only offers a direct link to the composer himself, it’s also a timely reminder of a now-vanished Soviet-era ‘sound’; rough, even raw, but always uniquely intense. (Although currently unavailable, perhaps we will get a newly remastered version in time for 2025.) Rudolf Barshai, who also knew and worked with Shostakovich, may not be quite as visceral as KK in this repertoire, yet he coaxes remarkably idiomatic playing from his north German orchestra (Brilliant Classics). Bernard Haitink’s full fifteen, much praised in its day, are somewhat patchy by comparison, a few of the recordings now sounding a tad bright (Decca). That said, his Concertgebouw recording of ‘Babi Yar’ is probably one of the most unforgettable things he ever committed to disc. By contrast, Mark Wigglesworth’s reading of that symphony is one of the few disappointments in his otherwise admirable traversal (review). Among the highlights are good performances of Nos 2, 3 and, especially, 12. As if that weren’t competition enough, there’s Kirill Petrenko’s nascent cycle with the Berliner Philharmoniker. On the strength of what I’ve heard so far – Nos 8, 9 and 10 – the completed set could sweep the board (review).

Given that Shostakovich’s Op 14 and 20 are Party-commissioned panegyrics – complete with toe-curling choruses – it would be all too easy to dismiss them out of hand. Although such pieces invite excess, judiciously done they can yield a few surprises. And that’s exactly how Nelsons plays them. As ever, he pays a lot of attention to structure and fine detail, the latter well caught by the very analytical engineering. Nelsons is good at building tension, too, the slow, louring start to No 2 imbued with a rare and compelling sense of drama. Many of the same virtues attend the Boston account of No 3, the clarinet solo at the start sounding more atmospheric than usual. Quieter moments are nicely articulated, with Nelsons maintaining a taut, energising narrative throughout. The agility of his players is a wonder to behold; the strings and woodwinds are especially impressive, the brass and bass drum as exciting as it gets. For all that, the recorded sound is drier than I remember from earlier instalments in the series. Also, the singing is somewhat lacking in weight and character; not necessarily a deal-breaker in these short pieces, but it could be in the much longer, chorus-driven ‘Babi Yar’.

It would be idle to pretend that those early efforts, and the much later Op 112, are great works, yet Mark Wigglesworth – ever the advocate – makes them seem much better than they really are. Yes, ‘The Year 1917’ can come across as bombastic – that extended peroration at the end is a case in point – but, in the right hands, this piece reveals a sure sense of shape and purpose. And while there are some good things in Nelsons’ performance, it all seems more efficient than persuasive, as if he isn’t entirely comfortable with this music. The Bostonians play with commendable spirit, the timpani and bass drum in ‘Aurora’ as thrilling as ever. Again, the sound seems a tad airless, and that flattens perspectives somewhat. In short, if you already have an aversion to the symphony, this new recording is unlikely to change your mind.

One can have no doubts about the strength and stature of Shostakovich’s Symphony No 13, which commemorates the Nazi massacre of 33,771 Jews at Babi Yar, near Kyiv, in September 1941. The hard-hitting texts, by the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, caused problems prior to the work’s premiere in 1962, not least because they berate the authorities and paint such an unprepossessing picture of life in the USSR. This, combined with the composer’s equally uncompromising score, makes for a formidable musical and emotional experience. Haitink’s performance towers – literally and figuratively – over all its rivals, the incandescent singing and playing matched by a truly remarkable recording. Up there, too, is André Previn’s 1979 version, recorded with the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, the latter directed by none other than the young Richard Hickox (review). I should also mention Kirill Karabits’s thoughtful, illuminating and deeply felt account of ‘Babi Yar’, recorded with the Russian National Orchestra and assorted choirs in 2017; anyone who loves this symphony should give it a try (review).

Alas, Nelsons’ performance disappoints on almost every level. As I feared, his backwardly balanced chorus lacks the body, bite and sheer volatility this powerful, penetrating score demands. Indeed, the singers, who ought to be a key protagonist in the drama, are relegated to the status of incurious onlookers. As for the soloist Matthias Goerne, a fine lieder singer, he’s sadly miscast here, struggling under pressure and frequently overwhelmed by Nelsons’ brash, overdriven climaxes. Even more dispiriting is the conductor’s leaden pace, his flaccid rhythms flirting with turgidity at every turn. This robs the music of all verve and vitality, reducing Shostakovich’s pithy, colourful score to dull shades of grey. The surprisingly flat, unengaging sound certainly doesn’t help. In short, it would be hard to imagine a more disastrous reading of ‘Babi Yar’ than this.

A dismal coda to an otherwise admirable cycle; variable sonics, too.

Dan Morgan

Help us financially by purchasing from