Gaetano Donizetti (1797–1848)

Don Pasquale, Opera buffa in three acts (1843)

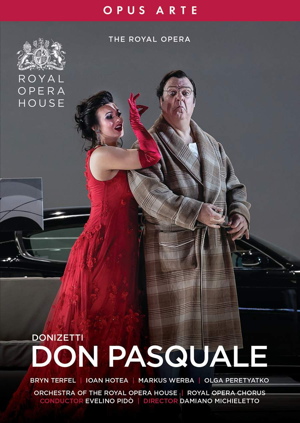

Bryn Terfel (Don Pasquale)

Markus Werba (Malatesta)

Olga Peretyatko (Norina)

Ioan Hotea (Ernesto)

Bryan Secombe (Carlino)

Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House/Evelino Pidò

Damiano Michieletto (stage direction)

rec. 24 & 30 October 2019, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London

Reviewed in surround sound

Opus Arte OA1315D DVD [145]

Gaetano Donizetti’s Don Pasquale is the last of the great opere buffe of the primo ottocento. It has also been his work most present on opera stages ever since – for good reasons. Late in his career, Donizetti knew all there was to know about exactly this type of opera, and it shows in the consistently high level of its invention. There is no falling off, as there sometimes was in the second halves of some of Rossini’s hastily written buffo works. This is a traditional tale of ageing bachelor thwarting young lovers who win out with the help of a scheming intermediary. The opera has four rewarding roles for skilled singers. The plot links back to the Italian renaissance commedia del’arte, and even to Roman times via the senex amans figure. As all the comedic operatic masterpieces, it needs to be taken quite seriously in the presentation of any new production. That is not always the case in this occasionally problematic but largely acceptable 2019 staging from Covent Garden.

The director’s treatment of the title role is a good touchstone. Don Pasquale is a man concerned about the future of his fortune, and wary of the plans of his nephew Ernesto to marry a poor young widow, Norina. He offers Ernesto a rich alternative spouse, and promises to set him up for life financially. This is not buffoonery or mad eccentricity on Pasquale’s part, for he is not a buffoon. This comedy must have pathos too. Pasquale’s fall only has that pathos if he is not a fall guy from the outset, but becomes one over the course of the trajectory he follows.

But Damiano Michieletto’s production makes Bryn Terfel’s Pasquale an unlikeable bully and a figure of fun from the start. He gurns a touch too often, sometimes is ridiculed by the production, struggles with his corset, dozes wearing his sunbed reflector. These may be legitimate visible aspects of his vanity, but there is an alternative view of a moderately dignified man in his middle years, bent on a course leading to ridicule. Even when Norina slaps Pasquale in Act Three – this is unhappily signalled early by her removal of the long glove from her right hand – we are not really stunned into shocked silence. It shows that the tone of the production is not quite right.

Yet there is some compensating pathos in Pasquale’s recall of his distant childhood and his mother’s affection, achieved with silent characters (mother and child) who share the stage. Puppetry is less successful. It requires Pasquale and Malatesta to handle large puppets while singing their famous Act Three duet (we are spared its traditional encore). At the end, stage hands are needed to come on and carry the puppets away for them. The puppets are earlier shown back-projected onto a very large screen, filmed live by an intrusive onstage video cameraman. This back-projection works well, though, when it shows Norina and Ernesto, whom we see onstage at the greenscreen, projected onto a nocturnal garden for their tryst in Act Three.

The set suggests the domestic space in which most of the action happens; this is achieved by the hanging outline of a roof made from fluorescent tubing. The house below has no walls, so the revolve allows us to see into all sides of the house. There is furniture, and interior doors without frames, which characters are required to open and close for privacy, even though the complete interior is visible to all.

The libretto sets no era for the opera, but one illustration of the mid-nineteenth-century premiere shows breeches, frock coat and crinoline among the costumes. Here we have an update to the middle 1900s, judging from Pasquale’s car, but Norina’s false assignation note appears only on her mobile phone. Rather than illuminating character and plot, production sometimes draws attention away from them. For instance, Ernesto pours black oil over Pasquale’s car. It is difficult to see how this illustrates their relationship beyond what we already know by this point. And the opera has enough of a reputation for cruelty without putting the perfectly ambulant Pasquale into a wheelchair at the very end, ready to be pushed away.

The singing, too, is mixed. Terfel’s debut as Don Pasquale is well sung, of course, even if we meet only a rather distant cousin to his superbly realised Falstaff in this house. That might be due to concerns with the production, but he deploys his bass-baritone in a manner less weighty for this bel canto piece, and he relishes details of the text to great effect. Soprano Olga Peretyatko was making her house debut, and the cheers at her curtain call show it was very well received. Norina seems an ideal role for her. She looks and sounds lovely, not least in her dazzling red ‘I’m going out alone’ costume. Her Act One So anch’io la virtù magica is a fine piece of singing, technically impressive.

Markus Werba has a relatively low-key stage presence for the schemer Malatesta, with a good if unvaried baritone sound, agile enough in the swift patter in the Act Three duet with Pasquale. Tenor Ioan Hotea is a rather under-characterised Ernesto; his pallid tenor sounds rather weak at times. But then it did not help that his nocturnal serenade Come’è gentil, the best known number in the score, is set so far away as to be almost inaudible.

Conductor Evelino Pidò and the orchestra are fine, as is the chorus which appears only in Act Three. There is very good surround sound and filming, if you do not mind close-ups of Terfel’s facial mannerisms, intended of course to be seen in the most distant seats. The short extra items on the disc involve lead singers, director and designers, and are reasonably informative about the production and the design.

I should in all fairness note that in 2019 this then new Don Pasquale was well received by many London critics, for the production and for much of the singing, Terfel’s especially. It has since been revived with some success. I do not know the other filmed versions, but it might be worth investigating those alongside this one.

Roy Westbrook

Help us financially by purchasing from

Other production staff

Chorus Director: William Spaulding

Set Designer: Paolo Fantin

Costume Designer: Agostino Cavalca

Lighting Designer: Alessandro Carletti

Screen Direction: Patti Marr.

Video details

Picture format:16:9

Sound format: PCM Stereo/DTS-HD MA 5.1

Region code: 0 (worldwide)

Sung in Italian

Subtitles: Italian, German, English, French, Korean, Japanese