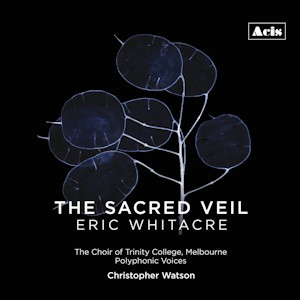

Eric Whitacre (b. 1970)

The Sacred Veil (2019)

Rosanne Hunt (cello); Rhodri Clarke (piano)

The Choir of Trinity College, Melbourne

Polyphonic Voices / Chrstopher Watson

rec. 2022, Robert Blackwood Hall, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia

Texts included

Acis APL54490 [57]

I think it’s essential to begin by summarising the background to the composition of The Sacred Veil. It’s another collaboration between Eric Whitacre and his close friend and frequent collaborator, the American historian and poet Charles Anthony Silvestri (b 1965). I can do no better than quote what Silvestri says about the genesis of the piece on his website: “This work features a series of poems written about my relationship with my late wife Julie [Lawrence Silvestri], her battle with ovarian cancer, and the grief I experienced as a result of her passing in 2005. This is the most intensely personal poetry I have ever written, and it evoked exquisite and heart-breaking music from composer Eric Whitacre.” Julie Lawrence Silvestri was only 36 when she died, leaving Silvestri to raise their two young children.

The work is cast in 12 sections, which play continuously, and the first poem in the sequence, ‘The Veil Opens’ provided the spur to the whole work. It’s a text which Silvestri gave to Whitacre after visiting him in 2016; in it he expresses the idea of a veil between the dead and the living. Whitacre says that the poet had not intended that these words should be set to music but he felt a compulsion to do so, after which further collaboration between composer and poet produced The Sacred Veil. Two of the work’s sections set no text: the choir sings wordlessly, yielding centre stage to the two instrumentalists. Five of the other sections are settings of poems by Silvestri but Whitacre himself provided the words for two sections and in the remaining three he set to music words written by Julie Lawrence Silvestri herself.

One of the three organisations which co-commissioned The Sacred Veil was the Los Angeles Master Chorale. They gave the premiere in 2019 under the composer’s direction and subsequently recorded it with him. That recording has been issued by Signum Classics (SIGCD630); I’ve not heard it. The present recording was made shortly after the present performers had given the Australian premiere, again conducted by the composer. For this recording, though, the conductor was Christopher Watson. His name may well be familiar to UK readers: as a singer he was a longstanding member of The Tallis Scholars and also performed regularly with several other crack European vocal ensembles, including Collegium Vocale Gent and the Gabrieli Consort. In 2017 he became Director of Music at Trinity College, University of Melbourne. It’s worth citing Watson’s past career as an expert consort singer because he’s clearly used that experience to train this cohort of singers very well indeed; the singing in this performance is excellent. The Trinity College choir is joined here by the Melbourne-based chamber choir, Polyphonic Voices. Together they combine as an ensemble of 38 voices (9/9/9/11). The score also includes important parts for cello and piano. As Paul Grabowsky explains in the booklet, the instruments fulfil a “narrative function…cooly observing the human tragedy unfolding around them”.

The booklet includes some explanatory comments by Whitacre. Amongst other things, he says this: “I knew that I would repeat texts and phrases three times every time I wanted to meditate on an idea, to formalise the poetry and to create a sense of stasis in the music”. I think that’s quite telling. I completely understand the wish to emphasis points through repetition – and he goes on to explain that the number three has other significances in the musical structure – however, the downside, to my ears at least, is a certain degree of repetitiousness in the music. I readily acknowledge, though, that other listeners may find this approach of emphasising a particular idea is helpful.

The texts are deeply personal. Indeed, one might argue that at times they are too personal. The prime example of this is section six, a poem entitled ‘I’m afraid’ into which Charles Anthony Silvestri has woven medical phraseology from his wife’s diagnosis; though Silvestri and Whitacre have decided to put this into the public domain, I had an uneasy feeling that I was intruding as I listened. Julie Silvestri’s own words in sections 4, 8 and 10 have an undeniable impact, though. I think the most effective section of all, both musically and poetically, is the penultimate one, ‘You Rise, I Fall’. Here, Silvestri writes of his wife’s last moments and his huge struggle to come to terms with losing her. He expresses the concept that as she dies, she rises whereas he, in losing her, falls. It’s noteworthy that in this section the harmonic language of Whitacre’s music is at its most intense and interesting. By contrast, Whitacre ends the work with ‘Child of Wonder’, a setting of his own words. Here, the harmonies are warm and consoling and the music is simple in design and very expressive as a result.

I hesitate to criticise a work that is clearly sincere and deeply felt; it is a work that one feels had to be written. However, for all the music’s undoubted sincerity I was left slightly dissatisfied. I first encountered Eric Whitacre’s music quite a few years ago when I enjoyed the beauty of pieces such as Lux aurumque. But I’m not sure that his compositional style has developed significantly since then. If I’m correct, then I think that’s a pity. The choral writing in The Sacred Veil is effective on its own terms – and especially so in the last two, highly contrasted sections – but I would have welcomed greater variety. The two sections in which the two instruments are to the fore offer valuable contrast but it would have been good, I think, if Whitacre had set some of the work for solo voice(s); indeed, some of the texts positively invite such treatment. Whitacre’s many admirers will take The Sacred Veil to their hearts, I’m sure but I’m not wholly convinced, though I don’t for one moment question the sincerity of either words or music. Whatever my reservations, though, Julie Lawrence Silvestri has been fittingly remembered in this piece. There can be no doubt that both words and music communicate very directly with the listener. As I listened, though, I wondered if The Sacred Veil is a work that is best experienced in live performance, when one can have a very direct communication with the performers, rather than through the medium of an audio recording.

I have no reservations at all about the performance standards. The choral singing is polished, accomplished and evidently committed. The contributions of cellist Rosanne Hunt and pianist Rhodri Clarke are consistently excellent; the wistful singing lines that Whitacre give to the cello catch the ear, all the more so since Ms Hunt plays them with such eloquence. Chrostopher Watson conducts the performance with conviction.

The production values are very good. The performers have been expertly recorded by engineer Mark Edwards and producer Michael Fulcher. The booklet is well produced. The only very slight caveat I have concerns the packaging. I commend Acis for using a carboard sleeve and avoiding plastic. However, both the disc and booklet are tightly packed into the sleeve pockets and there must be a risk of scuffing the surface of the disc as one extracts it, particularly if this is done on a number of occasions; the protection of a thin paper inner sleeve would mitigate this risk.

John Quinn

Availability: Acis